How to become an NFL referee? Start early.

Refereeing high school and college games is the way to work through the ranks. But it takes years – and some help – to become an NFL referee or MLB umpire.

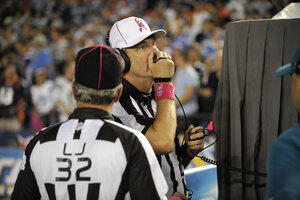

NFL referees make a call from the instant replay booth during an NFL football game between the San Diego Chargers and the Denver Broncos earlier this month in San Diego. To become an NFL referee takes years of working through the ranks.

Denis Poroy/AP/File

If there's a lesson to be learned from the recent NFL replacement referee debacle, it's this: Officials in the four major sports leagues are an elite bunch with difficult jobs. But what does it take to reach the top of the officiating game?

Referees go through many of the same selection stages as athletes. And their odds of making it to the top? "Minuscule," says Barry Mano, a former Division I college basketball referee. Mr. Mano is founder of the National Association of Sports Officials. "You have 121 people [working in the National Football League] right now. You have on the order of 70,000 football officials working high school and above."

That puts a ref's chance of making it to the NFL at 0.17 percent. In baseball, roughly 40 of the 300 students who enroll in umpire schools every year get called up to work in the minors. From there, about 2 percent will become one of the 68 umpires working in the majors, according to former Major League Baseball umpire Justin Klemm, who now serves as executive director of the Professional Baseball Umpire Corps, a Florida-based minor league subsidiary for training umpires.

Because of the time and experience required, an elite official gets in the game early, usually as a side gig for youth sports or junior-high-school games. For Mano, who started officiating in high school, it was a family thing: His father was also a basketball ref, and his older brother went on to officiate in the National Basketball Association. "I was getting paid 20 bucks per game to tell people what to do," he laughs. "It took me 12 years to get to the NCAA [National Collegiate Athletic Association]," where he made $400 per game.

Mr. Klemm says the timeline for a baseball umpire is roughly the same as that of a football ref: Begin at 22 or 23, and "if you're good enough, [you]will work your first MLB game in your early 30s."

Mano estimates that the NFL replacement refs, who were culled from the high school and small college leagues, came from gigs making $150 to $200 per game. Baseball umpires can make anywhere between $100 per game and $1,000 per series officiating college baseball. It's nowhere near the $90,000 to $300,000 made in the majors, but the travel demands are fewer, and even high school and college refereeing can make for a rewarding side gig.

As with athletes, it takes notice from a scout to pull an official up through the ranks. "It's a huge supply for a limited demand," Mano says. There are extensive character interviews, rigorous physical and psychological testing, and, at the highest levels, "a background check that would take your breath away."

At the top, life is a parade of travel, study, training camps, and physical conditioning. Though the NFL season only lasts five to six months, "part time" refs' obligations take up about 10 months. Baseball umps who are full-time MLB employees find themselves on the road for months at a time. Famed NFL ref Ed Hochuli is a partner at a Phoenix law firm; Mike Carey, head referee in Super Bowl XLII, owns a snow-sports equipment company. Others are tax consultants, lobbyists, and restaurant owners.

They have something in common. "These are risk-takers," says Mano, "with the flexibility of schedule to put the time in." The training and courage to make a quick decision and stand by it sorts out the superstar referees from the rest.

"You're getting criticized regardless, and you can't let it affect your work," Klemm adds.

And forget team allegiances. "Not part of our DNA," Mano insists.