Debt limit will get raised. But who'll vote to do it?

Raising the debt limit is about politics, not economics.

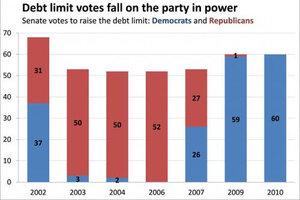

In the Senate, the party in power has typically been the one to raise the debt limit.

Donald Marron

Sometime this spring, Congress will vote to increase the debt ceiling. That vote won’t come easy. Newly ascendant House Republicans will threaten to withhold needed votes unless significant spending cuts or budget process reforms are attached to the measure. Democrats will denounce Republicans for threatening the government’s ability to pay its bills. And Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner will be forced into creative financing moves to buy Congressional leaders enough time to strike a deal.

But strike a deal they will. With monthly deficits running around $100 billion, the United States can’t cut spending or increase tax revenues enough to avoid further borrowing this year. It is equally inconceivable (I hope) that our elected leaders will decide to withhold payments from Social Security beneficiaries, our military, and our creditors.

So the debt ceiling will go up. And that means that at least 50 senators and more than 200 House members will cast a politically toxic yea vote.

Which lucky members will they be? The answer may well depend on what other budget provisions accompany the debt limit measure. That’s impossible to handicap today. In the meantime, though, we can look at past votes. They tell a clear story: debt limit votes are about politics, not principle.

Consider, for example, Senate votes on stand-alone debt limit measures over the past decade:

When Republicans held both the Senate and the White House (2003, 2004, 2006), they provided virtually all the yea votes, while almost all Democrats voted no. When the Democrats were in power (2009, 2010), the roles reversed: the Democrats provided all but one of the yea votes, while Republicans voted no. Only when government was divided – with a Democratic Senate and a Republican president (2002, 2007) – has the vote to lift the debt limit been bipartisan.

The House has taken fewer stand-alone votes than the Senate (because of the so-called Gephardt rule, which the Republicans abolished last week), but they show the same pattern: the party in power votes to increase the debt limit:

History thus suggests that Democrats will bear the burden of lifting the debt limit in the Senate; expect at least 50 yea votes. The only interesting question is whether individual Republicans filibuster the increase; if so, a 60-vote cloture measure would require at least 7 Republican votes as well.

Handicapping the House is more difficult since we’ve had no recent experience with divided government. If the Senate provides any guide, roughly equal numbers of Republicans and Democrats will ultimately vote for an increase. That would allow many Tea Party-backed Republicans to vote no without affecting the outcome. And other members might simply skip the vote. That’s what 21 members did in 2004, when it took just 208 votes to raise the debt ceiling.

Note: Congress increased the debt limit three other times during the past decade as part of larger bills: the 2008 housing act, the 2008 TARP act, and the 2009 stimulus. For simplicity, I have included all votes by Independents with the Democrats, since that’s how those members caucused during this period.

Add/view comments on this post.

--------------------------

The Christian Science Monitor has assembled a diverse group of the best economy-related bloggers out there. Our guest bloggers are not employed or directed by the Monitor and the views expressed are the bloggers' own, as is responsibility for the content of their blogs. To contact us about a blogger, click here. To add or view a comment on a guest blog, please go to the blogger's own site by clicking on the link above.