Why the debt ceiling isn't actually a ceiling on debt

Increasing the debt limit guarantees that the US will pay the debt it has – it doesn't stop the government from going deeper into debt. That requires unpopular policy changes.

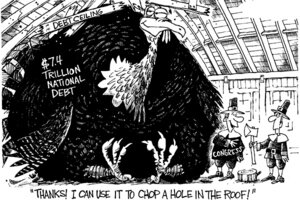

This cartoon first ran in November 2004. Every few years, Congress votes to raise the debt ceiling. Votes to shrink the debt are much rarer. In the image, two pilgrims (Congress) stand in a barn with a gigantic turkey (the then-$7.4 trillion national debt) crunched up against the ceiling (debt ceiling). One pilgrim hands an axe to the other who says, "Thanks! I can use it to chop a hole in the roof."

Joe Heller / Green Bay Press Gazette / File

Hmmm….. According to a Reuters/Ipsos poll released this week:

The U.S. public overwhelmingly opposes raising the country’s debt limit even though failure to do so could hurt America’s international standing and push up borrowing costs…

Some 71 percent of those surveyed oppose increasing the borrowing authority, the focus of a brewing political battle over federal spending. Only 18 percent support an increase.

Yet from the same poll (emphasis added):

Only 24 percent say the country can afford to cut back on education spending, a likely Republican target, and 21 percent support cuts to law enforcement.

With the Pentagon fighting wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, 51 percent supported cutbacks to military spending.

Less than half, 45 percent, support an expected Republican effort to pare environmental enforcement.

Some 53 percent support cutting the budgets of financial regulators like the Securities and Exchange Commission, in spite of the widespread consensus that a lax regulatory atmosphere contributed to the devastating financial crisis of 2007-2009.

And 47 percent support cutbacks to national parks, which were shuttered for several weeks during the budget battles of 1995 and 1996.

Expensive benefit programs that account for nearly half of all federal spending enjoy widespread support, the poll found. Only 20 percent supported paring Social Security retirement benefits while a mere 23 supported cutbacks to the Medicare health-insurance program.

Some 73 percent support scaling back foreign aid and 65 percent support cutting back on tax collection.

I wonder: is that supporting cutting back on “tax collection”–as in administrative and enforcement costs–or cutting back on taxes collected (i.e., taxes, period)?…

The Concord Coalition has updated our issue brief on the debt limit, which explains that holding the line on the debt limit would not literally stop the policies that increase our debt; it would simply cause us to default on our (still increasing) debt:

Approval of a debt limit increase is necessary to maintain the full faith and credit of the United States government. Failure to approve an increase would not be an act of fiscal responsibility, unless it can be said that deadbeats are fiscally responsible because they refuse to pay their bills. It would result in the United States defaulting on the commitments it has already made, including Social Security, Medicare and veterans benefits, vendor payments, tax refunds, student loans and interest payments on outstanding debt.

The consequences for government finances, the economy and financial markets would be dire as investors would no longer be able to count on U.S. bonds being the “safest investment in the world.” Delaying action on an increase until the last possible moment, forcing Treasury to utilize extraordinary measures to avoid a default, is unnecessary and irresponsible.

Unlike budget enforcement mechanisms such as statutory spending caps or the pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) rules for entitlement expansions and tax cuts, the debt limit places no restrictions on specific tax and spending decisions. If deficits result from these policy decisions, or if the economy fails to grow as projected, the debt limit must be increased to prevent a default on the government’s obligations.

Moreover, no plausible set of policy options have been proposed, nor do they exist, for preventing a breach of the current limit.

In other words, instead of holding the line on the costs of government spending, choosing to not increase the debt limit would dramatically raise the cost of maintaining our ongoing commitments by turning “safe” Treasuries into “risky” ones that would command higher interest rates.

Add/view comments on this post.

------------------------------

The Christian Science Monitor has assembled a diverse group of the best economy-related bloggers out there. Our guest bloggers are not employed or directed by the Monitor and the views expressed are the bloggers' own, as is responsibility for the content of their blogs. To contact us about a blogger, click here. To add or view a comment on a guest blog, please go to the blogger's own site by clicking on the link above.