Behind Europe's debt crisis lurks another Wall Street bailout

A Greek (or Irish or Spanish or Italian or Portuguese) default would have roughly the same effect on our financial system as the implosion of Lehman Brothers in 2008

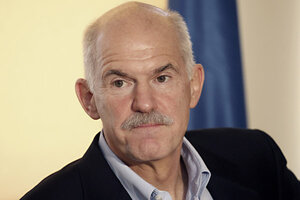

Greek Prime Minister George Papandreou is seen during a visit to the Financial Crimes squad at police headquarters in Athens. A string of missed fiscal targets has stoked fears that Greece - weighed under a massive debt load - is headed toward certain default, stalling the global economy's slow recovery from recession.

Petros Giannakouris/AP

Today Ben Bernanke added his voice to those who are worried about Europe’s debt crisis.

But why exactly should America be so concerned? Yes, we export to Europe – but those exports aren’t going to dry up. And in any event, they’re tiny compared to the size of the U.S. economy.

If you want the real reason, follow the money. A Greek (or Irish or Spanish or Italian or Portugese) default would have roughly the same effect on our financial system as the implosion of Lehman Brothers in 2008.

Financial chaos.

Investors are already getting the scent. Stocks slumped to 13-month low on Monday as investors dumped Wall Street bank shares.

The Street has lent only about $7 billion to Greece, as of the end of last year, according to the Bank for International Settlements. That’s no big deal.

But a default by Greece or any other of Europe’s debt-burdened nations could easily pummel German and French banks, which have lent Greece (and the other wobbly European countries) far more.

That’s where Wall Street comes in. Big Wall Street banks have lent German and French banks a bundle.

The Street’s total exposure to the euro zone totals about $2.7 trillion. Its exposure to to France and Germany accounts for nearly half the total.

And it’s not just Wall Street’s loans to German and French banks that are worrisome. Wall Street has also insured or bet on all sorts of derivatives emanating from Europe – on energy, currency, interest rates, and foreign exchange swaps. If a German or French bank goes down, the ripple effects are incalculable.

Get it? Follow the money: If Greece goes down, investors start fleeing Ireland, Spain, Italy, and Portugal as well. All of this sends big French and German banks reeling. If one of these banks collapses, or show signs of major strain, Wall Street is in big trouble. Possibly even bigger trouble than it was in after Lehman Brothers went down.

That’s why shares of the biggest U.S. banks have been falling for the past month. Morgan Stanley closed Monday at its lowest since December 2008 – and the cost of insuring Morgan’s debt has jumped to levels not seen since November 2008.

It’s rumored that Morgan could lose as much as $30 billion if some French and German banks fail. (That’s from Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council, which tracks all cross-border exposure of major banks.)

$30 billion is roughly $2 billion more than the assets Morgan owns (in terms of current market capitalization.)

But Morgan says its exposure to French banks is zero. Why the discrepancy? Morgan has probably taken out insurance against its loans to European banks, as well as collateral from them. So Morgan feels as if it’s not exposed.

But does anyone remember something spelled AIG? That was the giant insurance firm that went bust when Wall Street began going under. Wall Street thought it had insured its bets with AIG. Turned out, AIG couldn’t pay up.

Haven’t we been here before?

Republicans and Wall Street executives who continue to yell about Dodd-Frank overkill are dead wrong. The fact no one seems to know Morgan’s exposure to European banks or derivatives – or that of most other giant Wall Street banks – shows Dodd-Frank didn’t go nearly far enough.

Regulators still don’t know what’s happening on the Street. They have no clear picture of the derivatives exposure of giant U.S. financial institutions.

Which is why Washington officials are terrified – and why Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner keeps begging European officials to bail out Greece and the other deeply-indebted European nations.

Several months ago, when the European debt crisis first became apparent, Wall Street banks said not to worry. They had little or no exposure to Europe’s problems. The Federal Reserve said the same. In July, Ben Bernanke reassured Congress the exposure of U.S. banks to European nations in trouble was “quite small.”

Now we’re hearing a different tune.

Make no mistake. The United States wants Europe to bail out its deeply indebted nations so they can repay what they owe big European banks. Otherwise, those banks could implode — taking Wall Street with them.

One of the many ironies here is some badly-indebted European nations (Ireland is the best example) went deeply into debt in the first place bailing out their banks from the crisis that began on Wall Street.

Full circle.

In other words, Greece isn’t the real problem. Nor is Ireland, Italy, Portugal, or Spain. The real problem is the financial system — centered on Wall Street. And we still haven’t solved it.