‘Capital’ offense? Best-selling book calls for progressive tax on wealth.

'Capital in the Twenty-First Century,' by French economist Thomas Piketty is a dense, nearly 700-page historical treatise on economics that some are saying will be remembered as a watershed moment in our understanding of money. It was the best-selling book on Amazon last week.

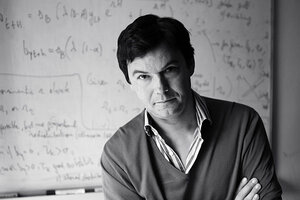

French economist Thomas Piketty poses for an undated photo provided by Harvard Press. In his new book, Piketty, who helped popularize the notion of a privileged 1 percent, sounds a grim warning: The US economy is beginning to decay into the aristocratic Europe of the 19th century.

Emmanuelle Marchadour/Harvard Press/AP/File

The top-selling book on Amazon last week wasn't a volume from the “Game of Thrones” saga, a tie-in to the movie “Frozen” or a boy’s tale about the reality of heaven. No, it’s a nearly 700-page historical treatise on economics that some are saying will be remembered as a watershed moment in our understanding of money.

“Capital in the Twenty-First Century,” by French economist Thomas Piketty, is a dense read, peppered with tables and charts and allusions. But it’s leaving all other books—even the latest by Michael Lewis, the great populist writer of all things money—in the dust.

The yawning disparity in wealth between average households and the super-rich is no secret. Even Google’s Eric Schmidt recently labeled the wealth divide as “the No. 1 issue of democracies.” But there has been a sense that this new Gilded Age is an aberration of our times, driven by the simultaneous rise of globalization, the might of China and the technological revolution.

Piketty’s research in “Capital” suggests the opposite—that we are seeing a historical return to the norm of wealth clustered in relatively few hands, and that the true aberration was the period from 1930 to 1975 when the world saw a more equitable rise of fortunes bootstrapped by governments during the Great Depression, World War II and the Cold War.

Piketty’s work takes aim at the central tenet that has guided economic policy in the West since the Reagan era—trickle-down economics, that “all ships rise” with the tide of wealth at the top. His examination of centuries’ worth of tax records in the U.S., France, the United Kingdom, Japan and Germany shows that wealth consistently “trickles up.”

The broad popularity of the book suggests that this “is being discussed with equal fervor by the world’s top economic policy makers and middle class Americans who wonder why they haven’t gotten a raise in years,” writes Rana Foroohar of Time magazine.

The book also takes aim at the American ideal that new wealth is largely born of sweat from the brow of entrepreneurs like Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk. Inherited money is a much bigger player than previously thought.

“The big idea of ‘Capital in the Twenty-First Century’ is that we haven’t just gone back to nineteenth-century levels of income inequality, we’re also on a path back to ‘patrimonial capitalism,’ in which the commanding heights of the economy are controlled not by talented individuals but by family dynasties,” Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman argues in the New York Review of Books.

“It’s a work that melds grand historical sweep—when was the last time you heard an economist invoke Jane Austen and Balzac?—with painstaking data analysis,” Krugman writes. “Piketty has transformed our economic discourse; we’ll never talk about wealth and inequality the same way we used to.”

With a title like “Capital,” and its inherent allusion to Karl Marx’s “Das Kapital,” there has been much suggestion that the book heralds the rise of “Millennial Marxism” (see also: “Marx Rises Again,” “The new Marxism” and “Taking On Adam Smith (and Karl Marx)).

Most alarming for the wealthy is Piketty’s prescription to turn the tide: an 80% tax rate on incomes starting at “$500,000 or $1 million” and a 50%-60% tax rate on incomes as low as $200,000—if only “to put an end to such incomes”—and a tax of 10%-20% on existing wealth. A skeptical Daniel Shuchman writes in the Wall Street Journal: “Instead of Austen and Balzac, the professor ought to read ‘Animal Farm’ and ‘Darkness at Noon.’”

If history is a guide, Piketty believes a modern “storming of the Bastille” will occur if taxation and finance policy don’t address the divide between the haves and have-nots.

“That’s one of Piketty biggest messages—inequality will slowly but surely undermine the population’s faith in the system. He doesn’t believe, as Marx did, that capitalism would simply burn itself out over time,” writes Foroohar. “But he does believe that rising inequality leads to a less perfect union, and a likelihood of major social unrest that mirrors the sort that his native France went through in the late 1800s.”