Slavery’s ‘lingering’ effects, reparations, and a hope of reconciliation

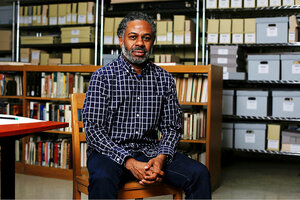

Community historian Morris “Dino” Robinson, who helped shape the Evanston, Illinois, reparations initiative, poses for a portrait at the Shorefront Legacy Center in Evanston on March 19, 2021. The initiative supports Black residents whose families suffered from discriminatory housing practices.

Eileen T. Meslar/Reuters

According to family historians on my mother’s side, my great-grandfather Louis Thompson was born into slavery in 1844. He was described as a mulatto, meaning that he was a product of the rape culture of the time. It was a common practice for slave owners to rape the women they owned. One result was the creation of additional wealth in the form of their own offspring. Yes, it is a horrific concept. And, no, there is no way to count how many times this particular crime of rape should be added to the crime against humanity named slavery.

After the Civil War, my great-grandfather acquired land in Louisiana where my grandmother was born. After college, she became a teacher. Her husband, my grandfather, earned his doctor of veterinary medicine degree at Ohio State University. Education, excellence, and hard work have been the hallmarks of my family through the generations.

Although I have long known that I am a descendant of slaves, I never gave much thought to reparations. African Americans never received the promised “40 acres and a mule” during Reconstruction. And although prominent thinkers, writers, and legislators have long promoted reparations, I considered the notion pie in the sky, so I didn’t waste time thinking about it.

Why We Wrote This

When something you’ve long ignored starts to gain national attention, it can be a wake-up call. That was the case for our commentator, who hadn’t given reparations any thought – until now.

But over the last few months, my consciousness has been raised.

“A societal debt”

At the end of February, I heard a talk by journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, who won the Pulitzer Prize for her landmark 1619 Project in The New York Times. She set my mind whirring when she described the Founding Fathers as “liars who didn’t believe in the values they touted.”

Ms. Hannah-Jones prompted me to do some research. She said that 10 of the first 12 U.S. presidents had been slave owners. That’s true, but the full list is longer. Among the first 12, Presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, Andrew Jackson, Martin Van Buren, William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, James K. Polk, and Zachary Taylor were slave owners, eight of them while in office. The remaining two, John Adams and John Quincy Adams, never owned slaves. Among later presidents, Andrew Johnson and Ulysses S. Grant were also slave owners.

Decades later, President Woodrow Wilson instituted practices that made it much more difficult for Black workers to overcome the economic impact of slavery. Specifically, he oversaw the segregation of much of the federal workforce, including the Treasury Department and the U.S. Postal Service. The dismissal of Black civil servants, their reassignment to lower-paying positions, the separation of work areas and facilities according to race, and a decrease in the hiring of Black employees rolled back economic progress with lasting effects on the Black community.

Noting that “anti-Blackness is foundational to the United States,” Ms. Hannah-Jones said, “Reparations from the U.S. government are a societal debt owed because of the racial apartheid that has been practiced.”

Then she added, “We are obligated to fight for progress that we don’t think we are really going to see.”

That got my attention. I still don’t expect to see a reparations check in my mailbox, but I am no longer ignoring the issue.

Reparations under discussion – and underway

Now that I’m paying attention, I’m seeing a number of important developments. Driven in part by Georgetown University’s history, Jesuit priests pledged in mid-March to raise $100 million for the descendants of people enslaved by the Roman Catholic order.

Also last month, the City Council in Evanston, Illinois, voted to offer reparations to Black residents whose families suffered from discriminatory housing practices. Evanston has committed $10 million over a decade to the effort, with the first $400,000 in payments going to a small number of eligible Black residents for home repairs, down payments, or mortgage payments.

Reuters reported on a plethora of initiatives in varying stages of consideration in cities ranging from Burlington, Vermont, to Asheville, North Carolina. A few Episcopal dioceses and a handful of universities have committed to reparations, too.

Critics have argued that, unlike the Evanston plan, the preponderance of reparations payments should go to individuals, not banks or contractors, to eliminate the racial wealth gap that descendants of slaves have endured. And we now have some sense of the size of that gap. Last summer, Citi Global Perspectives & Solutions calculated $16 trillion in lost gross domestic product over the past 20 years because of gaps between African Americans and whites in wages, education, housing, and investment.

But cash payments won’t correct the systems that perpetuate these gaps.

“Lingering negative effects”

My reading has made me wonder what reparations can and should repair. Are they a remedy for systemic racism? If so, they should target specific government programs and policies. Or are they a form of restitution for the crime of slavery? Many argue that the cost of the latter would be too many trillions to pay. However, we have two recent examples as precedents. Germany has paid some $91.9 billion to countries and people harmed by the Holocaust. And in 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed legislation authorizing $1.25 billion to be paid to the survivors of the 120,000 Japanese Americans interned during World War II – $20,000 per person. Another suggestion that might be easier to implement would be exempting several generations of African Americans from paying federal income taxes.

On Wednesday, a House committee approved H.R. 40, which would create a Commission to Study and Develop Reparation Proposals for African Americans. The 25-17 vote fell along party lines, with Democrats in the majority; no time has been set to bring the legislation to the floor for a vote. The bill charges the commission with identifying the following:

- Federal and state governments’ role in supporting slavery

- Public and private discrimination against freed slaves and their descendants

- “Lingering negative effects of slavery” on Black people and society

On the one hand, President Joe Biden says he supports the idea of studying reparations. On the other, aren’t commissions the places where good ideas are sent to die?

There is no way to know yet how or whether any of the nascent reparations efforts will mature. What is beginning to happen, though, is real consideration of too-long-ignored realities. At a minimum, a conversation has begun in earnest. And I hope that conversation leads to something the U.S. has never had, a national truth and reconciliation process on the impact and aftermath of slavery.

That type of process has brought some measure of healing to South Africa and Northern Ireland. Perhaps it could help the United States begin to bridge our bitterly partisan and demographic divides.

Jacqueline Adams is co-author of “A Blessing: Women of Color Teaming Up to Lead, Empower and Thrive.”