Why local news is necessary

Remember the dogged, wisecracking reporters of yore? As in “Good Night, and Good Luck” and “All the President’s Men”? That spirit is still alive.

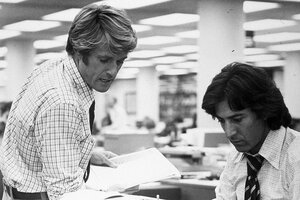

Robert Redford (left) and Dustin Hoffman star in “All the President’s Men,” a 1976 film about the Watergate scandal. Today, journalism is in trouble.

Warner Bros./Newscom/File

At one time, everyone wanted to be a journalist. Well, not everyone, but a large number of students entering college did. It was the late 1970s. An investigation led by two Washington Post reporters had resulted in President Richard Nixon’s resignation on Aug. 9, 1974. The movie version of Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward’s exploits, starring Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman, had arrived two years later. “All the President’s Men” won four Oscars. Who wouldn’t want to be a journalist? Those guys had just helped save American democracy!

It didn’t last, though, and today journalism is in trouble. Craigslist wiped out classified ads, and Google has taken care of the rest, pretty much. It appears that many people get their news from a big-tech aggregator on their smartphones. (One could note with irony that Apple News is strangely dependent on the very news originators it is arguably undermining by drawing away subscribers.)

Small local newspapers have been hit especially hard with rising costs, falling revenues, and even targeting by hedge funds that essentially loot and then discard them. The effect of these and other pressures has been the rise of vast, local news “deserts” across the United States.

But remember the dogged, wisecracking reporters of yore? The hard-boiled editors with hearts of gold? As in “The Front Page,” “Good Night, and Good Luck,” the aforementioned “All the President’s Men”? Or the dear-to-print-journalists but underseen “The Paper” with Michael Keaton? That spirit is still alive and out there.

In this week’s cover story, Monitor correspondent Doug Struck set out to see how local newsgathering operations are trying to save themselves through radical reinvention. An online startup in Mansfield, Ohio, hosts monthly concerts in its shared-space newsroom. In Saline, Michigan, the community wouldn’t let a local publication fold after its editor reluctantly decided that he had to quit. In Weare, New Hampshire, the local library stepped up to fill a news void. Philanthropists are bankrolling some publications. Other news entrepreneurs are simply starting up and hoping the money will follow.

At its best, a local news source, which can take many forms, helps knit a community together and strengthens its identity by helping citizens respond to local needs. It’s also a guardian, the eyes and ears of the public in town meetings and councils.

Good government flourishes in the sunshine, and our nation’s founders knew that. “A press that is free to investigate and criticize the government,” wrote Thomas Jefferson, “is absolutely essential in a nation that practices self-government and is therefore dependent on an educated and enlightened citizenry.” But the provision for a free press to enlighten the citizenry is a hollow promise if there’s no publication to practice it.

So who needs local news? Jefferson would say “everyone.” But in case you’re not convinced, look at it this way: When five burglars broke into an office at the Watergate Hotel in Washington on June 17, 1972, it was a local story. Mr. Woodward and Mr. Bernstein were unknowns; The Washington Post had virtually no national profile.

And Nixon was president.