How we see climate science

At this point, peer-reviewed science points to a significant and accelerating human impact on the climate. But catastrophe need not be inevitable.

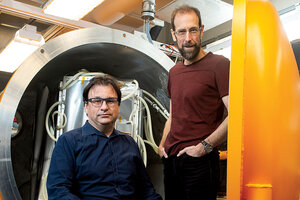

Frank Keutsch (left), professor of engineering and atmospheric science, and David Keith, professor of applied physics, stand in front of a testing area for technology for the Stratospheric Controlled Perturbation Experiment their team is designing at Harvard University.

Ann Hermes/Staff

One of the most frequent questions I get from Monitor readers is: Why are you taking a side on climate change? This question usually comes from the standpoint of someone doubting the catastrophic forecasts if urgent action is not taken. But the answer to the question is important, no matter what one’s view of climate change. So this week, in conjunction with Simon Montlake’s fascinating cover story on the ethics of a worst-case solution, I want to talk about how the Monitor views climate science – and one bias we do have.

To me, the debate over climate science speaks to a misunderstanding about how science journalism works. I was a science writer for the Monitor, and many of my stories came from one general source: peer-reviewed studies. This wasn’t because I was lazy or closed to other viewpoints. The whole point of peer review is to subject science to the most rigorous test possible – to let the most knowledgeable people in a field cast a skeptical eye and decide what the best science is.

As much as laboratory work, peer review is a foundation stone of the scientific process, so it is also foundational to science journalism. And at this point, peer-reviewed climate science points to a significant and accelerating human impact on the climate.

Now, some people note there are scientists with different opinions. In many cases, these skeptics are not climate scientists, and just as one would not go to a car mechanic to get a computer fixed, science journalists should not base climate reporting on work by scientists from other fields. In other cases, alternative findings have not passed peer review, and the Monitor would be unwise to start reporting on non-peer-reviewed science.

Is it possible that in this polarized era even scientists are shaped by their ideological bubbles, and peer review has been tainted by a climate change “bias”? That is a vital question for journalists to ask, but at this point we’ve found no evidence that would invalidate the body of current peer-reviewed climate science.

There is one place, however, where the Monitor clearly does have an opinion – that the catastrophic scenarios need not be inevitable. Fifty years ago, overpopulation was thought to be an imminent crisis. One biologist estimated 4 billion starvation deaths by the 1980s. By contrast, famine deaths are at historically low levels. Science’s Green Revolution changed the equation for how productive agriculture can be.

That’s not a perfect analogy, but it points to how expanding knowledge can reveal new answers. It would not be wise to trundle on blindly, saying “knowledge will fix climate change.” But it would also be foolish to think that the tools we have now are the only tools we will ever have. And the Monitor has a bias for seeking out those scientific frontiers that point to where our capacity might grow and yield solutions still over the horizon. The worst-case remedy in Simon’s story might not be a real solution, but it speaks to an intriguing way that knowledge is expanding in the search to find one.