James Madison foresaw the big question worrying voters. What did he say?

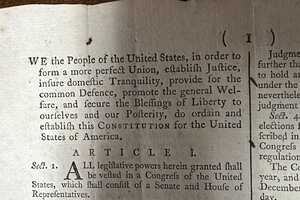

Part of a 1787 copy of the U.S. Constitution is shown at Brunk Auctions in Asheville, North Carolina, Sept. 5, 2024.

Jeffrey Collins/AP/File

Some 236 years ago, it would seem that James Madison foresaw this moment.

Election Day in the United States has arrived, and the great question that lies ahead is one he spent no small amount of time attempting to answer. How does a nation with democratic principles prevent the winners from walking all over the losers?

Madison’s answer was a masterstroke of realpolitik. In political factions, he saw the human tendency to be whipped into groups of passion and ill will toward others. And in the clash of faction on faction, he saw checks and counterbalances.

Why We Wrote This

Many American voters say they’re anxious about who wins. What happens to the losing side? James Madison thought deeply about that question, and we the nation has learned more since.

Yet as Americans go to the voting booth today, I wonder: Is there really no moral element?

On one hand, both sides claim ample moral rectitude. But is morality, too, merely split among warring factions? Today’s politics would seem to be an example of fractured morality making factions burn hotter. Is there no practical morality that transcends and encompasses?

In looking across the world several decades ago, political scientist Samuel Huntington noticed something he called the “two turnover test.” The idea is that democratic governments are only stable when they survive two turnovers of power without collapsing. In other words, losing is what tests a nation’s stability and strength.

The practical reason is obvious. If one side refuses to lose, then democratic government becomes impossible. But there is a moral element at play, too. Transitions of power can only come when there is trust, because without trust the loser will feel vulnerable. The diversity of faction upon faction can provide some protection, as Madison surmised. But this election, a great sense of uncertainty comes from the concern that these checks and balances – as well as those enshrined in the federal government – have been compromised.

At some point, does trust need to come from actual trust – not from faction on faction, but from care for one another?

This might seem like precisely the dewy-eyed idealism Madison rejected. But it is not without success. Again and again I look to the example offered by nonviolent movements from India to South Africa to the U.S.

Historian Taylor Branch called the civil rights leaders America’s “second Founding Fathers.” Why? Because they pointed to a new mode of power beyond the calculations of faction on faction. They pointed to higher principles that created healthier democratic action. Love was proven to be effective political policy.

Madison’s wisdom remains. Today, the U.S. faces the challenge he knew presented a threat to the nation, then and now. As American citizens trust one another less, the question of how to protect the rights of the loser have proportionally grown. It has now reached a new pitch.

What is the way out?

To me, history shows that thought does not move without sacrifice – without transformative commitment to something larger than one’s own opinions and desires. We saw that in America’s first and second foundings. We see a need for it now.

The way of faction asks the sacrifices of time and comfort to fight for what we think is most important, pitted against those who do the same on the opposite side. But there is another sacrifice we can make – yielding our own wants and fears to a larger sense of love. And history also suggests that, in the end, this alone can build the trust that promises a better society for all.