After Mitt Romney's speech, voters may still ask: Can we trust him?

Mitt Romney’s acceptance speech at the Republican National Convention last night was a tepid mix of boilerplate and biography, vague on policy, economical with the truth, and without a memorable, soaring line. It reflected all of the problems that have bedeviled Romney from the outset.

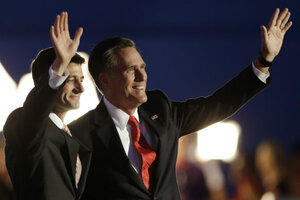

Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney and vice presidential nominee Rep. Paul Ryan wave following Mr. Romney's speech during the Republican National Convention in Tampa, Fla. Aug. 30. Op-ed contributor Kurt Shillinger observes: 'Romney’s accomplishments provide plenty of reassuring notes….But along the way he has sown many doubts about his core convictions and principles, and may, if he wins, find himself bound to a plan he could not explain and cannot implement.'

Charlie Neibergall/AP

St. Louis

After nearly six years of seeking the Republican presidential nomination, Mitt Romney stood before his party and the nation with one imperative task last night: to make the case that President Barack Obama has failed and present himself as a reliable and necessary alternative.

Put more succinctly, he needed to establish trust.

It started well, with Mr. Romney entering the Republican National Convention hall not from behind the stage curtains but down the aisle as if he were entering a joint session of Congress. A convention without pomp is wasted circumstance, and this was well-crafted political theater. It presented an often awkward candidate as both presidential and metaphorical – a man of the people, chosen by the people, rising up the open steps to the podium from the ranks to lead the people. It was a distinctly American moment.

But the acceptance speech that followed was a tepid mix of boilerplate and biography, by turns heart-warming and quizzical, vague on policy, economical with the truth, and without a distinctly memorable and soaring line. In short, it reflected all of the problems that have bedeviled Romney from the outset. That shortfall is as unfortunate as it is hard to understand, and increases the possibility that as the campaign season moves into its final two months Romney may never quite explain himself.

At a time when the economy is the overriding concern of Americans of every demographic category, Romney touts an impressive resume. He is a more qualified candidate than Barack Obama was four years ago, and his record includes impressive successes in both the private and public sectors. In some of his better lines, he urged voters to separate their emotional ties to Obama and their dashed hopes.

Yet trustworthiness remains an abiding question about Romney. In a poll released on the eve of the convention, the Pew Research Center found that while impressions of Romney have improved since the primaries, “42 percent of the words volunteered by respondents are clearly negative, most commonly liar, arrogant, crook, out of touch, distrust and fake.” And the report continues: “Fewer (28 percent) offer words that are clearly positive in tone, such as honest, good, leadership, and capable.”

Two comments this week from his own team illustrate a contradiction. Capping a tender personal portrait of a dedicated family man, hardworking professional, and generous neighbor, Ann Romney declared: “You can trust Mitt.” Outside the convention hall, meanwhile, Romney pollster Neil Newhouse pushed back against media criticism of distortion and blatant dishonesty in the campaign’s messages by saying, “We’re not going to let our campaign be dictated by fact-checkers.”

Which is it? Romney repeated several of the most discredited claims of his campaign in his acceptance speech about Mr. Obama’s plans for Medicare and reforms to welfare. He accused Obama of divisiveness and partisan gridlock when, as veteran congressional watchers Norman Ornstein and Thomas Mann have documented, his own party – and indeed running mate Paul Ryan – were willing to vote against measures they themselves co-sponsored rather than reach accord with the president. His disingenuous claims are numerous.

This is not to deny that Obama and the Democrats have stretched the truth and played politics. Rather, it raises valid questions about how Romney’s relationship with his own party would shape the way he might govern.

Across the arc of his political career, dating back to his bid to oust Massachusetts Sen. Ted Kennedy in 1994, Romney can be found on multiple sides of almost every issue. The pattern suggests political expediency more than evolving views – even if that means willfully obscuring or even denouncing some of his most notable political achievements. He has moved steadily toward the right in pace with the Republican party, but even this maneuvering has not silenced niggling doubts that he is neither a true conservative nor a viable candidate.

Even as delegates line up behind him, Govs. Chris Christie of New Jersey and Rick Perry of Texas could not help hinting at an interest in running four years from now.

If he wins, can he tack toward the center to find enough votes on both sides of the aisle to enact his agenda? Based on the fate of long-serving moderate Republican legislators like Rep. Christopher Shays of Connecticut and Sen. Richard Lugar of Indiana, it seems unlikely that Romney will find much flexibility within his own party’s base and caucus.

And that’s the real problem. Romney’s goals are lofty: 12 million jobs, a reformed tax code, fiscal discipline, energy independence, a strong military, and better education opportunities. Easier said than done – and, so far, Romney won’t say how they would be done. Independent economic analyses have not been able to work the math.

For the second consecutive presidential election, a major political party has lifted its standard bearer from a community historically barred from the White House: an African American four years ago, a Mormon last night. The most remarkable thing about overcoming those barriers is how unremarkable it almost seems in the moment.

In both the last election and this one, with stakes running high, voters are looking for competent leadership, wherever it might be found. Romney’s accomplishments provide plenty of reassuring notes. His determination and motivation are evident. In style and substance, his early political record and roots are those of a more pragmatic centrist.

Nonetheless, his pursuit of a more favorable political alignment has finally brought him the nomination of his party.

But along the way he has sown many doubts about his core convictions and principles, and may, if he wins, find himself bound to a plan he would not explain, cannot implement, and perhaps does not entirely embrace.

Kurt Shillinger is a former political reporter for The Christian Science Monitor. He also covered sub-Saharan Africa for The Boston Globe.