How President Obama can forge a nuclear deal with Iran

Ahead of crucial 'P5+1' talks on Iran's nuclear program in Kazakhstan Feb. 26, President Obama needs to show willingness to meet Iranian concessions with some of his own. But Congress is in no mood to ease sanctions. Obama, however, can go around Congress.

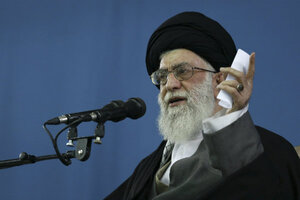

Iran's Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei speaks to a crowd in Tehran Feb. 16. To pave the way for a deal with Iran on its nuclear program at upcoming P5+1 talks, op-ed contributor Reza Nasri says President Obama can pledge 'that if Iran makes concessions on its program, he will suspend executive sanctions (as opposed to congressional ones) and revoke asset seizures that were conducted through executive orders.'

Office of the Supreme Leader/AP

Toronto

It is clear by now that President Obama will likely never persuade Congress to lift its crippling sanctions on Iran even if Iran agrees to make significant concessions on its nuclear program. If anyone had any doubt about how hostile Congress is even to the mere idea of easing pressure on Tehran, watching the Senate Armed Services Committee's treatment of Chuck Hagel at his confirmation hearing for secretary of Defense should have put that doubt to rest.

Pressuring Iran is no longer just a matter of tactical policy for Congress. It's a deeply institutionalized ritual that every member is expected to partake in.

This is a sad reality that Tehran is fully aware of – one that Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Iran's Supreme Leader, tacitly acknowledged last week after the Obama administration implemented new congressional sanctions: He said that Iran would not be negotiating with America simply “for the sake of negotiating.” Iran wants a negotiating partner that can actually deliver on a promise to normalize relations and reciprocate concessions with mutual concessions.

As Congress has made this implausible for now, bilateral talks between Tehran and Washington are not likely to take place any time soon. On the other hand, the United States and Iran will inevitably meet to negotiate the latter's nuclear program in the context of the multilateral "P5+1" talks scheduled to take place in Kazakhstan on Feb. 26.

So, what can Mr. Obama do in order to maximize diplomacy's chance of success despite structural congressional strictures? The answer is clear: Explore and exercise those foreign-policy options that cannot be easily hindered by Congress.

Ahead of these crucial negotiations, the president can do several things.

For one, he can pledge before the talks begin that if Iran makes concessions on its program, he will suspend executive sanctions (as opposed to congressional ones) and revoke asset seizures that were conducted through executive orders. The Treasury Department's Office of Financial Assets Control (OFAC) has tremendous latitude that Obama can use to ease pressure on Iran.

Making such a pledge would signal to Tehran that Washington is genuinely committed to making a deal, while setting a new tone for US allies in their approach to Iran. After all, if Obama takes this approach, they, too, would need to see that there will be a difference between the Iran policy of his first and second terms.

Second, while the president cannot control his own Congress, he can certainly work with the European Union and other allies, such as South Korea, Japan, Canada, and Australia, to make sure that they lift their own sets of sanctions against Iran if a reasonable agreement is reached.

It is true that parliamentary procedures and executive decisions in those countries are also clogged by political considerations and various lobbies when it comes to dealing with Iran. But pressure from the American government would prompt these US allies to transcend “domestic politics” and cooperate with Washington in its effort to settle the nuclear crisis.

In working with America’s allies, Obama would also signal that he's not only capable of uniting the Western world against Iran, as has been the administration's motto for the past four years, but that he's also able to unite them in conciliation with Iran when it's needed.

By insisting on this tired “united against Iran posture,” the US and its Western allies are only exhibiting a patronizing attitude that is depriving Iranian leaders from conceding to a face-saving solution. Obama has the authority to change this climate and pave the ground for diplomacy to succeed.

Finally, the president can also – without the hindrance of Congress – reactivate the United Nations' dormant capacities and use them in favor of the upcoming negotiations. For example, his State Department can work with members of the Security Council to produce a pledge, through a “presidential statement,” that the UN body would lift its own international sanctions against Iran if an agreement is reached, notwithstanding previous resolutions.

This non-binding UN instrument would provide Iran the incentive to make concessions more confidently (knowing that its cooperation would be met with some degree of reciprocation). It would also give Western countries the assurance that adopting a more flexible approach on the question of uranium enrichment would not breach previous UN resolutions against Iran, set a bad precedent, or dent the integrity of the Security Council.

Considering that Iranian Foreign Minister Ali Akbar Salehi has already declared that Iran is ready to translate Ayatollah Khamenei's religious fatwa against nuclear weapons “into a legally binding, official document at the UN,” bringing a reciprocal UN document to the table would certainly help boost confidence between the parties before the start of the negotiations.

After more than a decade of Western pressure on Iran that has achieved no deal on its nuclear program, a change of approach is in order. Time is running out, and the ball is in President Obama's court.

Reza Nasri is an international lawyer specializing in Iranian affairs and charter and foreign relations law at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva.