Key signs that Al Qaeda's Islamic extremism is moving into southern Africa

A surge of sectarian strife and Al Qaeda-linked terrorism in Tanzania signals that Africa's jihadist wave is expanding south. The failure of the international community to assist Tanzania in tackling the roots of Islamic extremism will likely allow it to grow.

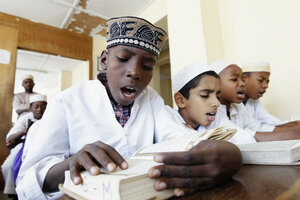

A student recites the Koran at Al-Nour Islamic school in Stone Town on the island of Zanzibar during the holy month of Ramadan, July 21, 2012. Op-ed contributors Jay Radzinski and Daniel Nisman say 'it could only be a matter of time before Al Qaeda’s veteran terrorists...take note of Tanzania’s revitalized extremist potential....It remains the responsibility of stability-seeking nations to uproot those elements before it’s too late.'

Thomas Mukoya/Reuters/file

Tel Aviv

“I pointed out to you the stars, and all you saw was the tip of my finger.” This Tanzanian proverb should resonate deeply with anyone who fears the spread of Islamic extremism in Africa. On Tanzania's island paradise of Zanzibar, the killing of a Catholic Priest by Muslim extremists last month points to a series of mounting and long-ignored signals that the continent’s jihadist wave is expanding south.

As witnessed in Somalia and Mali, the failure of the international community to assist Tanzania in tackling the roots of Islamic extremism will likely allow it to grow.

Located in southern Africa on the Indian Ocean, this traditionally tranquil tourism hub has been awash with sectarian strife since October 2012. It began when a dispute between two local school children resulted in the defilement of a Koran, sparking outrage by Tanzania’s large Muslim community. At least four churches across the country were attacked in the aftermath in what may just prove to be a watershed moment in Tanzania’s modern history.

In February 2013, religious tensions in Zanzibar continued to simmer from a dispute over butchering rights, sparking tit-for-tat attacks between Christians and Muslims, ultimately resulting in the beheading of one priest and the fatal shooting of another inside his own church. A self-proclaimed local Al Qaeda branch calling itself “Muslim Renewal” took credit for the shooting as its inaugural attack.

But 14 years before this latest unrest in Zanzibar, Tanzania took center stage, after a deadly bombing attack at the US embassy in Tanzania’s biggest city, Dar es-Salaam, with all fingers pointing to Al Qaeda militants. This event, along with the bombing of the US embassy in Nairobi, brought names like Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri into the public sphere for the first time.

Then-President Clinton responded by launching cruise missiles at Al Qaeda bases in Sudan and Afghanistan. Despite the participation of local East Africans in the attacks, little concrete measures were taken to curb radicalization in the region.

By May 2012, the global jihad network would rear its ugly head in Tanzania once more, after a bombing attack occurred in the Kenyan capital, targeting a prominent shopping district. While blame was placed squarely on Somalia’s Al Shabaab Islamist group, the arrest of a German national in Tanzania in connection to the attack largely went unnoticed. The man, reportedly of Turkish descent, had undergone training in Al Qaeda camps in Pakistan.

While the Tanzanian link in the global-jihad chain failed yet again to ring alarm bells, deteriorating domestic conditions may open the floodgates for a homegrown wave of extremism.

Tanzania’s delicate demographic balance is divided into thirds among Christians, Muslims, and animists. The country maintains a secular charter with careful restrictions against religion in politics since the end of socialist rule in the 1990s.

Under this system, Tanzanian Muslims have commonly accused the government of discrimination. In 2002, the Tanzanian government instituted the Terrorism Prevention law under pressure from the United States. The law ultimately resembled the US Patriot Act, and served to further increase mistrust of local Muslims toward police and the central government.

These deeply rooted tensions have been compounded by the impact of the global economic recession, with communal violence against Christians just one of the apparent outcomes.

With Western influence in fast retreat along with foreign aid cuts and budget reductions from nongovernmental organizations, wealthy Arabian Gulf donors have helped nurture an Islamist revival across the country. That's been evident in a subtle rise in Swahili-translated Korans on bookshelves, Islamist satellite TV channels, and increasing attendance at Friday sermons. In Zanzibar alone, Saudi Arabia continues to invest more than $1 million per year in Islamic universities, madrasas, and scholarships for young Zanzibari men to study abroad in Mecca.

This rising tide of Islamism has drawn concern from Tanzania’s Christian leaders. In recent months, they have become increasingly vocal in accusing Saudi Arabia and Sudan of sending Islamic preachers to the country with the aim of spreading sharia law from the predominantly-Muslim Zanzibar islands into mixed areas in mainland Tanzania.

Back on Zanzibar, leaflets were distributed in Christian communities in early March that called for retaliation for the recent priest killings, threatening to further exacerbate sectarian violence on the impoverished island. Christian preachers elsewhere in the country have since complained of receiving ominous text messages from the Muslim Renewal group that stated: “We will burn homes and churches. We have not finished: at Easter, be prepared for disaster.”

In an all-too-common trend, it could only be a matter of time before Al Qaeda’s veteran terrorists elsewhere in the world take note of Tanzania’s revitalized extremist potential. The combination of economic strife and religious conflict provides fertile ground for these elements to sow their seeds of instability.

It remains the responsibility of stability-seeking nations to uproot those elements before it’s too late. Religious fundamentalists must no longer be the sole source of funding for Tanzania’s impoverished Muslim communities. Schools that preach extremism must be replaced with those that teach math, science, and tolerance. The Tanzanian government should be given aid conditional to its investments in infrastructure, while its security forces must be given guidance on community policing and other best practices in good governance.

Time is running out. As the West continues to reel from its mistakes in neglecting the developments in Mali and Somalia, Tanzania is emerging as a backdoor for Islamic extremism – one that should be slammed shut before it’s too late.

Jay Radzinski and Daniel Nisman are the Africa and Middle East division intelligence directors at Max Security Solutions, a global geopolitical and security risk consulting firm.