Prison reform: Seize the moment

Both parties realize that the exploding prison population is unsustainable. Sentencing reform is one step in the right direction.

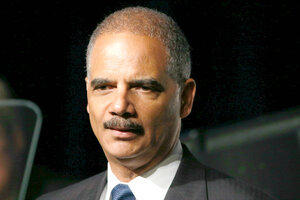

US Attorney General Eric Holder speaks at the annual meeting of the American Bar Association in San Francisco Aug. 12. The Justice Department plans to change how it prosecutes some nonviolent drug offenders, ending a policy of mandatory minimum prison sentences.

Stephen Lam/Reuters

The time is right for reform of the badly overcrowded US prison system. The growing cost of incarcerating so many Americans (the United States has 5 percent of the world’s population but 25 percent of its prisoners) has pushed even politicians who are tough-on-crime to seek fresh solutions.

Today, Attorney General Eric Holder weighed in on behalf of the Obama administration. He called for sentencing and other reforms, particularly for those convicted of drug-related crimes, that will begin to reduce the number of inmates in federal prisons. That number now stands at 219,000, about 40 percent above the prisons' official capacity.

Holder added to what is already a compelling fiscal argument for reform by highlighting the moral costs of mandatory sentences, which fail to take into account the specific circumstances surrounding a crime.

Mandatory sentencing laws enacted decades ago in an effort to bypass “too lenient” judges now look dated and inflexible in an era of diminishing crime rates. As a result, the thinking of some conservatives has taken a 180 degree turn. Instead of being “tough on crime,” mandatory sentences have become just one more part of big government running roughshod. They “reflect a Washington-knows-best, one-size-fits-all approach,” ignoring the principle “that people should be treated as individuals,” says Sen. Rand Paul (R) of Kentucky.

One expected policy change will direct federal prosecutors not to describe the specific quantity of drugs involved in a crime, thereby avoiding mandatory sentencing laws tied to those amounts. These cases would have to meet certain criteria first: The defendant could not have used violence or a weapon, could not be a suspected leader of a criminal gang or cartel, and could not have any significant criminal history. “We need to ensure that incarceration is used to punish, deter, and rehabilitate – not merely to convict, warehouse, and forget,” the attorney general says in his draft.

He also calls for a compassionate policy toward elderly inmates who have not committed violent crimes and who have already served a large portion of their sentences, recommending that they receive early release from prison. These inmates are among the most expensive to incarcerate because they often require much more medical care than younger prisoners.

While the US population has grown by about one-third since 1980, the population in prisons has grown 800 percent. That alarming disproportion has caused states such as Arkansas, Kansas, Kentucky, and Texas to have already put in place programs that are reducing their prison populations. The federal government now is following in the footsteps of these innovative state programs, which use treatment or probation as alternatives to incarceration when deemed appropriate.

Mandatory sentences have, at least in some part, played on Americans’ anger about crime and their fear of being a victim. They have been a way to ensure that the guilty don’t use what are seen as legal loopholes to avoid severe punishment. But these laws also have swept up others not deserving of such harsh treatment with their broad broom.

Today, fear of crime is not high on the public agenda, but cutting government spending is. These twin trends have opened the way for fresh approaches to prison reform. The administration and Congress should follow up with bipartisan legislation that will continue the process.

The political moment has arrived to create a more flexible, effective, fair, and compassionate prison system.