A deal to glue a divided Afghanistan

An American-brokered deal to resolve the presidential election in Afghanistan aims to create a unity government, one that may bridge ethnic divides and tackle corruption.

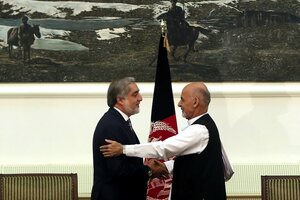

Afghanistan's presidential election candidates Abdullah Abdullah, left, and Ashraf Ghani Ahmadzai, right, shake hands after signing a power-sharing deal at the presidential palace in Kabul, Afghanistan Sept. 2.

AP Photo

Any deep split in a nation’s identity, such as over language or religion, can leave it open to corruption, say experts on honesty in governance. For Afghanistan, which is ranked as one of the world’s most corrupt countries, the split has largely been along ethnic lines. Yet a deal announced Saturday to create a government of national unity has the potential to narrow the rift.

The deal, which was brokered by the United States, will result in a power-sharing arrangement by the two winning candidates of a disputed election for president last June. Ashraf Ghani, an ethnic Pashtun and the final winner based on a United Nations-supervised audit of the vote, will become president. And his rival, Abdullah Abdullah, who is half-Pashtun, half-Tajik, can either run day-to-day governance or appoint someone else to do so.

The two men’s respective voting bases reflect Afghanistan’s historical ethnic divides. Ever since the US invaded the country in 2001 to oust the Taliban, it has tried to convince Afghans to see themselves as one civic polity. So far, the US has spent more than $100 billion in nation-building. And even after a drawdown of American forces by 2016, it plans to spend billions more.

If the two leaders can govern together, they will help create a stronger national identity, one that may close the door on ethnic-based corruption. More transparent and accountable government in Afghanistan will strengthen the Afghan military and leave less room for the Taliban to expand its influence.

Mr. Ghani, a former finance minister and professor in the US, says the defeat of the Taliban depends on the fight against corruption. Young people especially need to identify with elected leaders and government institutions, he says. They will only do that if they perceive rule of law and the appointment of civil servants by merit. He plans to set up a national procurement.

The outgoing president, Hamid Karzai, was widely seen as less than vigilant against corruption. Still, new laws, such as one on mining, taxes, and anti-money laundering, are steps forward in battling graft. Afghanistan’s future source of wealth may lie in an estimated $3 trillion in minerals, such as iron and copper. As foreign aid declines, the country must find more political cohesion to avoid the potential pitfall of a contest to exploit its natural resources.

The widespread fraud in the presidential election, and then the threats and squabbling over who should be declared the winner, did not do much to heal the identity rift in Afghanistan. The US had to use its own threats to arm-twist the leaders to agree. Doubts remain about whether the deal will hold. The Constitution must be changed. And a dragging economy needs a lift.

Yet, over the past 13 years, Afghanistan has made much progress to build on. Its income levels have doubled while its ranking by the World Bank as a place to do business has improved. Girls are being educated. Women represent more than a quarter of legislators.

Afghanistan cannot go down the same round as Iraq, where divisions over religion (Sunni-Shiite) led to a weakened democracy, demoralized military, and an opening for the Islamic State group to advance.

Despite its flawed election, Afghanistan will have its first peaceful, democratic transfer of power with Ghani becoming president. But with an election for parliament only two years away, this unity government must race to operate with openness and honesty. Such qualities are tight glue for any nation.