It’s back to voters to curb partisan gerrymandering

The Supreme Court’s decision not to get involved with an inherently political process throws the responsibility back to citizens to decide the boundaries of their political communities.

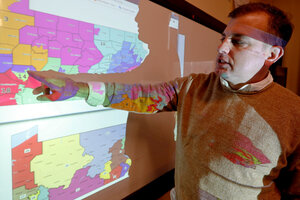

William Marx points to images of the old congressional districts in Pennsylvania on top, and the re-drawn districts on the bottom, while teaching civics in Pittsburgh last year. He was was a plaintiff in a lawsuit that successfully challenged the Republican-drawn congressional maps in the state.

AP

When the U.S. Supreme Court takes on a big case, it usually assumes it has the authority and wisdom to decide what would be a fair ruling. Yet on one historic issue in American democracy – state legislatures drawing the boundaries of voting districts to favor one party – this was not to be. On Thursday, the justices decided that gerrymandering is too inherently political, complex, and unpredictable for federal courts to set a workable legal standard.

The ruling now throws the problem of gerrymandering back to citizens and their state representatives. “The avenue for reform,” wrote Chief Justice John Roberts for the 5-4 majority, “remains open.”

The high court did join the chorus of complaints over gerrymandering, which is a type of winner-take-all tactic that can discourage voters from participating in civic life. But it admitted courts are ill-equipped to tell states what a fair voting district would look like.

The court reasoned that voting districts are political communities that must, through a mix of competitive and cooperative politics, define the fairness of each community’s boundaries. Courts can ensure each person has an equal vote and that racial minorities do not suffer discrimination. But on the question of how to group voters in the shifting sands of diverse interests over time, it is up to individuals and their representatives to join together and conceive the identity of each political community. In their choices of elected leaders, voters can help determine how to allocate power during the redistricting that is required every 10 years after each census.

With the outcry over gerrymandering at a peak, Justice Roberts did point to efforts in several states to find solutions. These include referendums, independent commissions, or the designation of demographers to draw up political maps based on certain criteria. The framers of the Constitution knew that redistricting would be difficult and political. They set up a system in which voters themselves, rather than federal judges, would be forced to find common ground.

Voters are capable of discovering the collective good in the exercise of designating voting districts. But this restraint on partisan politics will require them to respect the views of others, listen for shared concerns, and define what is fair in the democratic process.