Texas communities embrace 'toilet-to-tap' water: Will California follow suit?

As the historic drought that has gripped the state of California for four years drags on, Golden State officials are grasping for innovative solutions and eyeing Texas's foray into toilet-to-tap water with keen interest.

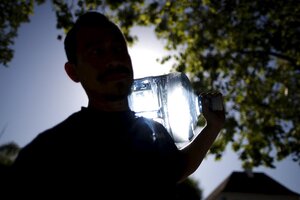

A Sparkletts bottled water delivery worker carries water to homes in Los Angeles, April 17. Officials in drought-strapped California are grasping for innovative solutions to dwindling water supplies, including so-called toilet-to-tap wastewater treatment.

Lucy Nicholson/Reuters

Dallas

Lessons learned in – until recently – drought parched Texas could help inspire a so-called toilet-to-tap water revolution in drought-ridden California.

The only places in the United States known to have implemented the practice of turning treated wastewater into drinking water without passing treated water through an environmental buffer are in the Lone Star State.

Big Spring and Wichita Falls, Texas, employ what is known as a direct, potable reuse (DPR) technology to supplement scarce water resources.

Wichita Falls connected its treated wastewater pipeline to the city’s water supplies last year. Big Spring, located in the dry environs of west Texas, beat its state compatriot in north Texas to the punch in 2013.

As the historic drought that has gripped the state of California for four years drags on, Golden State officials are grasping for innovative solutions and eyeing Texas's foray into toilet-to-tap water with keen interest.

Getting treated wastewater back into the water supply minus the environmental buffer could be a boon for the Golden State, says Richard Mills, chief of the water recycling and desalination section in the California Department of Water Resources.

“DPR is important because, in the long run, it is expected to allow greater use of treated wastewater at a reasonable cost to help meet our water demands,” he says. This comes, he continues, “in an era where freshwater supplies in many cases are near their limits of capacity.”

As Calfornia's drought situation has become increasingly dire, municipalities have already started to see shower, dishwashing, and toilet waters as a valuable resource. Orange County has been replenishing depleted groundwater reserves with treated household wastewater for several years. The direct potable reuse technique pioneered in Texas, however, offers a quicker and potentially more cost-effective process, Mr. Mills says.

Unlike indirect processing systems, which require multiple piping systems to pass the water through an environmental buffer such as gravel or a natural water body to further treat wastewater, direct potable reuse systems can utilize existing potable distribution systems, says Mills.

"While DPR is expected to cost more for water treatment and monitoring than other forms of wastewater reuse, there would be cost savings from eliminating the need for a separate pipeline distribution system to get the the treated water to customers, Mills says.

The California State Department of Public Health is currently conducting a study considering the feasibility of employing direct potable reuse in the state. That report is due by Dec. 31, 2016. Mills says the aim is to have a regulatory framework in place before allowing treated wastewater to be turned into drinking water across the state. If California is successful, the state could be a beacon for not only other water-starved states in the West but others around the country, Mills says.

In Texas, the $13-million system employed by Wichita Falls sends chlorine-treated wastewater from toilets, sinks, dishwashers, washing machines, and bathtubs directly to the plant where water is purified for drinking water. There, it is combined with lake water where it undergoes more disinfection, microfiltration, reverse osmosis, and ultraviolet light treatment.

The city rushed into action after officials realized they were two years away from running out of water. “The city experienced its worst single year drought in 2011, when we had 100 days over 100 degrees and precipitation that was 40 percent of normal,” says Daniel Nix, utilities operations manager for Wichita Falls Public Works department. “That dropped our lake levels from 87 percent to 60 percent. At the beginning of 2012, when we calculated the worst-case projection of lake levels using a repeat of 2011 weather patterns, it was obvious we were going to be out of water by the summer of 2013. So we needed to do something quick.”

Since the system started operating, it has produced 2 billion gallons of treated water.

In Big Spring, there was a greater imperative. Locals were already relying on bottled water due to the low quality source water. That, combined with low rainfall and speedy evaporation, presented the city with a problem. Big Spring ended up with a system similar to that of Wichita Falls, recovering an estimated 2 million gallons per day.

Of course, cities have had to overcome public perception obstacles – with residents describing an ick factor. Initial reports saw some Wichita Falls residents balk at the thought of toilet water – despite its treatment – going into the drinking water supply.

"Everyone I know is buying bottled water," Ronna Prickett, co-owner of Polka-Dot Penguin gift shop told the Huffington Post last year. "People at the city have been telling us to have faith in the system but there is a stigma attached."

But people have generally come around, according to Nix and the local Wichita Times Record News. Residents say the water flowing from the tap tastes better, the Times Record News reported. In August, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality in August awarded the city’s drinking supply its highest possible rating.

At the time it was launched, Gidget's Snack Shack owner Julia Spence told NPR, "You do have to give them the benefit of the doubt, because they have done their research, they've spent a whole lot of money, they've tested, tested, tested."

In general, Wichita Falls residents welcomed DPR as a necessary step in ensuring reliable water supplies, Mr. Nix says. “They knew we were running out of water and time.”

In the United States, less than 10 percent of wastewater is repurposed, according to WateReuse, an advocacy group based in Alexandria, Va. The advanced nature of treatment technologies has rendered "virtually any source" potentially usable, says Melissa Meeker, the group's executive director. “This means the concept of wastewater has become obsolete.”