WIPP seals off nuclear waste for 10,000 years. Should it be a model for storage?

Shut down after two 2014 incidents, New Mexico’s Waste Isolation Pilot Plant accepted its first new shipments of nuclear waste last week.

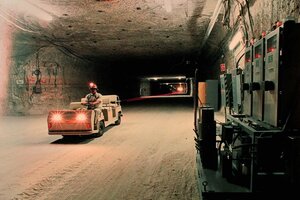

A worker drives an electric cart past air monitoring equipment inside a storage room of the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in Carlsbad, N.M. , shown in this undated photo.

WIPP Information Center handout/AP

In late 2013, operators at a Los Alamos nuclear lab stuffed the wrong kind of kitty litter into a waste drum and shipped it off to Carlsbad, N.M. Deep below the earth, at the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, a chemical reaction popped open the drum and sent small amounts of radioactivity ascending to the surface, contaminating nearly two dozen workers.

That now-infamous accident, coming less than two weeks after a fire hospitalized six workers at the underground plant, shut down WIPP for three years. Last Monday, it accepted its first new shipment of transuranic nuclear waste – contaminated gloves, clothing, tools and other radioactive materials – from an Idaho facility.

There could be plenty more on the way: almost 80,000 cubic meters of contaminated material, most of it contact-handled, could be shipped to WIPP in the future, according to a 2016 Department of Energy inventory report, and the department will also bring in diluted batches of what was once weapons-grade plutonium from South Carolina’s Savannah River Site.

Carved into an ancient deposit of salt 2,150 feet beneath the soil, WIPP is the only underground repository for radioactive materials in the country. And it embodies the regulatory philosophy that governments ought to get nuclear materials off their hands entirely, rather than trying to safeguard them above ground.

Its reopening may resurface ongoing debates over the use of underground repositories, with regulators in the United States and other countries pointing to WIPP-style sites as the safest option available for storing nuclear waste – though one often greeted with skepticism by local lawmakers and the public, not to mention environmentalists.

“Can you prevent what happened in the future going forward? The department determined that absolutely yes, you can – and identified quite significant changes,” including improved procedures at sending plants and new waste-management contractors at Los Alamos, says David Klaus, Department of Energy deputy undersecretary for management and performance from 2013 to January 2017.

“If you look at the records in Los Alamos, they show you that they followed their rules – they just changed them without anyone watching them,” he says. “When they went from nonorganic to organic kitty litter, it’s in the documents. We know when they did it.”

President Trump’s budget features a $120 million plan to store high-level waste beneath Nevada's Yucca Mountain, though it’s unclear how much traction it could get. Originally drawn up in the early 1980s, opponents like former Sen. Harry Reid (D) have successfully sidetracked a Yucca Mountain repository for decades, and public disfavor is widespread.

But wheels are turning in Europe and other countries. Finland will begin storing uranium in an underground repository on the island of Olkiluoto in 2023. France’s parliament approved a Bure clay formation for housing high-level waste in July 2016, though legal and political challenges could still block it. And Canada, Japan, Sweden, and Britain are exploring various underground storage options, such as limestone and granite.

Since the accidents at WIPP, investigators and regulators have produced judgments on what went wrong, implemented a recovery plan and installed a new ventilation system. The state of New Mexico, meanwhile, settled with the DOE for $73 million in infrastructure projects.

Opened in 1999 after decades of opposition from locals, the site hummed along without incident for 15 years, winning over area lawmakers as a source of jobs and income. And local officials have not raised serious qualms with the reopening. Partly because of that lack of political opposition, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) concluded in January that WIPP remains a “success story of a repository for defense nuclear waste.”

But in some quarters, doubts linger about whether use of such repositories are really safer than above-ground storage.

The idea behind using a salt bed to house waste is that the salt will eventually collapse and encase it in a pocket that water can't penetrate. Once WIPP is full, sometime around 2033, the site will be decommissioned and sealed off, and eventually, markers warning future generations of what lies beneath will be installed on the surface land above.

A 'very good piece of salt'

At WIPP’s predecessors – the Asse II and the Morsleban sites in Germany, former salt mines converted into nuclear waste repositories in the 1960s and 1970s – German officials have concluded, in recent years, that those sites should never have been chosen in the first place, after significant water penetration was discovered.

But the Carlsbad salt deposit, which was mined out specifically to hold waste, is different. Charles Forsberg, a nuclear engineer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Mass., who has directed studies on the handling of nuclear fuel, describes it as a “very good piece of salt.”

“The geologists have been pretty unanimous since the ‘50s that salt’s a good disposal media because it seals shut,” he says. “In the end, geological disposal depends on the specific site. And it’s just in a big, deep chunk of salt.”

Still, in many of the countries where repositories are on federal agendas, citizens' groups are sounding alarms. In Canada, where the world's fourth such repository is being contemplated in a limestone deposit less than a mile from Lake Huron, opponents are pointing to the leaks at other repositories as an indication that they might not be as sound of a solution as regulators believe.

Don Hancock, a longtime critic of WIPP who directs the Nuclear Waste Safety Program at the public-interest Southwest Research and Information Center, says he has warned Canadian officials against underground repositories.

“I said, you need to be careful about how much you know and how good the scientific and engineering work is on operating these facilities, because the Germans and US are pretty sophisticated folks, and if they can’t, the Canadians ought to be a little cautious about it, too,” he says.

“Generally, there’s a consensus [among scientists] that putting [nuclear waste] a few thousand feet underground is safer than leaving it on surface,” he adds.

But officials can at least monitor waste above ground, even if safety isn’t guaranteed. “When you put it underground you are intentionally losing control of it.”

“I’m not opposed to the concept of geologic disposal, but it’s going to take a long time to figure out how to do it right. And in the meantime, more time, effort and money needs to go into how to keep it safer on the surface over the next several decades.”

[Editor's note: This article has been updated to correctly identify the distance of a proposed limestone-based repository in Canada from Lake Huron; to clarify the categorization of waste interred in the WIPP facility and the timing of the initial packing of the organic kitty litter; and to clarify the kinds of substrate under consideration for repositories in Canada, Japan, Sweden, and Britain.]