Is ditching fossil fuels entirely a reasonable goal?

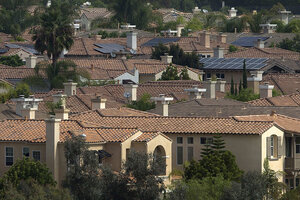

Solar power plays a starring role in California's vision for a 'decarbonized' future. Earlier this month, the California Energy Commission unanimously approved a mandate requiring solar energy installations on all new homes by 2020.

Mike Blake/Reuters/File

Washington

Something remarkable happened in California during the day of April 28: The most populous state in America met 73 percent of its electric power needs from renewable energy sources, mostly solar and wind.

That doesn’t even count the gobs of largely off-grid electricity generated by residential rooftop panels in the state – supplies that are poised to surge thanks to a new regulatory mandate that all new homes generate solar power.

So is California heralding a new era of abundant clean energy – and fast “decarbonizing” its economy by leaving fossil fuels behind?

Why We Wrote This

As some states map a low-carbon energy future, an important debate is shaping up: How diverse will the mix of energy sources need to be?

Not so fast. The reality is that, as some states seek to adjust their energy profile in response to climate change, a big challenge looms. Solar and wind energy, while popular and increasingly cheap to produce, varies based on whether the wind is blowing or the sun shining. Any ideal of “100 percent renewable” energy will need to grapple with how to meet power needs day and night, all seasons of the year.

It’s a formidable task, and it’s actually the tip of a deeper issue: States and nations are entering uncharted waters with efforts to rapidly pivot toward clean energy. Big technical hurdles – like what to do after the sun goes down – are matched by the political test of maintaining public support for steps that, as much as they may help humanity’s future, also impose some costs.

“There’s more research saying it's going to be extremely inefficient and costly to run a grid solely on variable energy like the sun and the wind – even if you allow for heroic progress on energy storage,” says Danny Cullenward, an energy economist who serves on an independent advisory commission on California’s climate policies.

And when the price tag rises for action on climate change, he adds, “those costs will eventually be seen and will affect the politics.”

That doesn’t mean support for greening the energy system is about to crumble in states like California and New York. But costs do matter, even in liberal states, at a time when about one-third of Americans say they doubt global warming is caused mostly by human carbon emissions.

“I’m optimistic ... we’ll find affordable ways to get this done,” Dr. Cullenward says of the energy transition. But “it's not a small undertaking.”

States are providing some trial-and-error lessons along the path.

A tale of two states

Where sunny California is going all-in on solar, New York has its own ambitious plans that look more like an “all of the above” clean-energy strategy, including nuclear power.

California, by contrast, is on course to phase out its remaining nuclear capacity, based on concerns about safety and maintenance costs. But that means that California, like New York, still relies heavily on fossil fuels: natural gas for electricity, plus of course gasoline in transportation.

Climate scientists widely agree that human emissions are behind observed warming in the Earth’s surface temperatures and oceans, and that action to reduce greenhouse emissions is an urgent global priority.

California and New York are arguably America’s leaders on this front, as large states that have set ambitious goals. Yet even they are feeling their way on a journey where it’s a lot easier to get to a 50 percent reduction in emissions than to achieve the more complete “decarbonization” of economies that scientists see as the real target.

“We haven't figured it out just yet,” Cullenward says.

But these states have their feet moving, alongside nations that signed onto the 2015 Paris Agreement to pursue lower greenhouse-gas emissions. Their efforts could bring benefits, not just burdens, to their economies.

“China is taking lessons from California and New York right now,” says Kate Gordon, a fellow at the Columbia University Center on Global Energy Policy in New York. “We’re in a policy context right now globally where most countries in the world have agreed to bring carbon emissions down 80 percent by 2050…. That just opens the door to technological advances,” including job creation for places that take leadership roles.

“We always underestimate the power of technological innovation to address these issues,” she says.

Consider that challenge of solar- and wind-power variability. The issue is real, but potential solutions are in view.

“I think it’s a problem we can solve,” says Ethan Elkind, an energy-law expert at the University of California, Berkeley. “I think we’re heading toward a solar-plus-storage future.”

“Storage” means improved ways of saving variable power for when it’s needed, from batteries at residences to molten salt at larger utility-run solar installations.

But it’s unclear how fast that will become affordable and efficient enough to have a large-scale impact. So other parallel solutions could include:

- Managing the demand for power, such as using apps and price incentives to encourage activities like dishwashing or car-charging when power is most available.

- Making power grids better connected, so more power can flow across time zones.

- Having an energy mix that includes not just solar and wind but also “dispatchable” or always-on sources like natural gas. That wouldn’t mean giving up on zero-emission aspirations, if carbon-capture technology allowed greenhouse gases to be stored underground or adapted for industrial use.

Some experts predict that each of those steps will be needed, especially as cars are increasingly electrified.

And alongside the technical challenges are the political ones. Economists say the most efficient way to cut emissions is through marketplace incentives, like a tax on emissions or making the price of electricity vary with undulations in supply and demand. Such price signals, unlike specific government mandates, allow markets to determine which solutions are the cheapest path to less carbon.

“I believe you can reach any carbon goal using market-based policies,” says Lucas Davis, an energy economist at the Berkeley Haas School of Business in California. But “it would require the political will of maintaining higher prices on carbon than we currently have.”

This issue is a live one. New York is considering a new carbon tax. And on Thursday a legislative committee in California heard arguments that the state’s economy-wide “cap and trade” program for emissions needs to be more stringent.

In practice, states are trying both price signals and regulatory mandates in tandem to coax the energy transition forward.

The mandate for rooftop solar panels in California is the latest example. Critics say the mandate is a gimmick that will make homes more expensive in an already high-cost state. But another view is that homebuyers will see the panels pay for themselves, and the result will be new fans of clean-energy policies.

“It turns this from [theory] to something that people can really see and experience,” says Ms. Gordon of the Columbia energy center. “That makes solar real to people, and that makes this whole set of [clean-energy] solutions accessible.”