Transforming air pollution into talk-provoking art

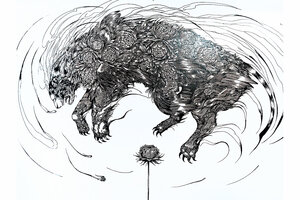

Illustrator Kristopher Ho used ink made from air pollution for works he displayed at a 2016 exhibition in Amsterdam.

Courtesy of Kristopher Ho

It started with a simple observation. The air in densely populated cities like Mumbai and New Delhi is so thick with pollution that a white shirt can be dotted with black flecks by day’s end.

While many environmental efforts focus on ways to filter air, a graduate of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Mass., saw another opportunity – turn exhaust into ink for art.

As a graduate student from New Delhi, Anirudh Sharma began experimenting in 2013 with the idea of turning carbon pollution into ink at MIT’s Media Lab. By 2016, he had returned to India and recruited a team of inventors to establish Graviky Labs. There they developed tools to capture pollution and created Air-Ink markers.

Why We Wrote This

Sometimes big problems can be hard to see. This start-up in India aims to shine a light on air pollution by transforming it into ink.

Today the Bangalore-based company has produced 1,000 liters of ink (about 260 gallons) that have been distributed to 55 countries and to artists around the world. Their $25-30 Air-Ink markers, which come in various sizes, are set to be released in United States markets in the fall of 2018.

But Graviky Labs produces more than an innovative ink, says co-founder Nikhil Kaushik. It transforms an invisible scourge into something tangible. In that sense, the ink makes as big a statement as anything artists use it to create.

“[The markers] make pollution more of a tangible topic, [because] you can see it. It makes people curious about the amount of pollution,” says Boston-based artist Sneha Shrestha, who is preparing a solo show in Boston in the fall featuring works created solely with Air-Ink markers. “I get to have a conversation about how … this amazing product is not just collecting pollution, but making something out of it. This opens ways for conversation.”

Air pollution, which is often dubbed the silent killer, is especially pervasive in India. About 1.1 million deaths are attributed annually to air pollution exposure in India, according to a 2015 survey by the US-based Health Effects Institute. That’s a quarter of the total deaths attributable to air pollution world wide.

Graviky Labs’ device, called Kaalink (which means black ink in Hindi), can be fitted onto the exhaust pipe of a car or on a small chimney stack to collect the soot that forms from the incomplete burning of fossil fuels. Once captured, the pollution undergoes a process to separate the heavy metals from the carbon to make the ink that goes into the markers and bottles. In the future, the company hopes to find use for the separated metals. For now, they are disposed of as industrial waste.

“The concept of recycling gets reaffirmed in this process. We [usually] print with inks that are not eco-friendly, [but with Air-Ink] you are using eco-friendly solutions … because you are not burning fossil fuels,” says Mr. Kaushik.

One marker on average holds approximately 30 to 35 minutes of car pollution from Bangalore, says Kaushik. While artists are drawn to Air-Ink’s environmental purpose, on an aesthetic level the markers also deliver a high quality ink.

“I thought it was just a gimmick [at first],” says Kristopher Ho, a Hong Kong-based artist who was one of the early testers of the markers. “But then they turned out really good, surprisingly good.” He has used Air-ink markers to paint murals in London, Amsterdam, and Hong Kong. “Normally regular ink … tends to be quite watery, but Air-Ink is a lot stickier and thicker … and doesn’t bleed as much.”

For Ms. Shrestha, who paints under the name Imagine, using Air-Ink markers also holds a personal significance. The native of Nepal often uses the inks to write on handmade Nepali paper and views her work with the markers as a marriage between Nepal and India, which similarly struggle with air pollution.

“Creating beauty of pollution, that’s very innovative … and it’s kind of mind-blowing,” she says.

For now, Graviky Labs is focusing solely on finding ways to scale up the deployment of Kaalinks and on reducing the costs of the markers to make them more accessible to the general public, says Kaushik. It is their hope that one day their efforts will no longer be needed. However, until then, they intend to continue finding innovative solutions to inspire others to join the fight against air pollution.

“We just want to contribute in any manner we can. When you come into an idea like this and put it to scale, a lot of people [also] come up with their own ideas, and I think that’s the most important thing. You [are allowing] the process to become [quicker] because individuals are taking [matters] into their own hands. As citizens, we also need to do our part of [the] job.”