Clean energy storage on the cheap in new flow battery

A new battery developed by Harvard scientists uses an inexpensive chemical and a unique structure to address the intermittent nature of wind and solar power.

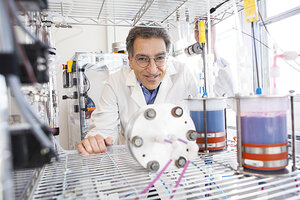

Harvard researcher Michael Aziz handles a new flow battery designed to bolster clean energy. The battery uses quinones, organic molecules similar to those that store energy in plants and animals.

Eliza Grinnell/Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences

How can we bottle the sun and wind for when we really need it?

Scientists across the globe are working to answer that question, with the hope it will unlock the full potential of energy sources that are theoretically limitless, but notoriously inconsistent. A group at Harvard University's School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) believes they have taken a step forward, developing a new battery that inexpensively stores wind and solar energy.

The group's work, published Thursday in the scientific journal Nature, will undergo years of additional research and development to determine the battery's ultimate potential. But early results are promising, says lead researcher Michael Aziz, and help address renewable energy's greatest challenge.

"If we want to produce a large fraction of electricity from solar and wind ... we need to be able to do something when the wind isn't blowing and the sun isn’t shining," Professor Aziz, who teaches materials and energy technologies at SEAS, says in a telephone interview. "Right now we burn fossil fuels – so if we could store that [wind and solar] energy when the wind isn't blowing, the sun isn't shining, we could consume a lot less fossil fuels."

Today's batteries won't suffice. The traditional lead-acid batteries used in most cars lose power quickly, and advanced lithium-ion batteries use rare, expensive metals. Those technologies hold potential for future breakthroughs, but scientists are also looking for structures and chemicals that are cheaper and more plentiful than batteries already on the marketplace.

Most of the energy we store today goes into solid structures that combine the two essential parts of a battery: the chemicals used to store energy, and the devices that convert it to electric power. But the SEAS team's battery is a so-called "flow" battery, which decouples those two components. External tanks hold energy stored in chemicals, which flow through electrodes to generate power when needed. Those tanks can be easily scaled up or down to match the specific needs of a certain wind farm or solar array.

Flow batteries aren't new, but they come at a cost. The most advanced commercially available flow battery uses Vanadium, Aziz says, a chemical element that costs between 0.9 cents and 1.8 cents per kilowatt hour (kWh) delivered over the course of 10,000 cycles (essentially recharges). Add in the materials and manufacturing costs, and Vanadium flow batteries cost well over a penny per kWh – the price target set by the Department of Energy, which funded the SAES group's work.

For their battery, the Harvard scientists and engineers used quinones, organic molecules similar to those that store energy in plants and animals. Because they are naturally abundant, Aziz says they cost only about 0.27 cents per kWh.

It's significantly cheaper than Vanadium, but the other materials and manufacturing processes needed at commercial scale could push the cost over the coveted penny per kWh mark. And so far, Aziz's team has only tested the new flow battery through around 100 cycles. It will need to demonstrate that the battery can handle thousands of depletions and recharges for it to be commercially viable.

If it works, utilities could add these tank-like batteries to the base of wind turbines or at the edge of solar arrays to squirrel away enough energy to sustain consumers through two cloudy, windless days. The battery might also someday show up in homes.

"We could have a device about the size of heating oil tank in the basement that would store a day’s worth of energy from the sun on a typical home rooftop solar system," Aziz says, "and allow that energy to be used at will – for example, overnight – without burning fossil fuels."

The team is partnering with Connecticut-based Sustainable Innovations, LLC to develop a demonstration unit within the next three years.