The US is losing the clean energy race. Why that's OK.

Collaboration – not competition – is key to a clean energy future in the US, China, and beyond, writes Alex Trembath of The Breakthrough Institute.

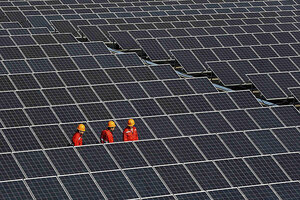

Workers walk among solar panels in Zhouquan township of Tongxiang, Zhejiang province in China. China has bet on a wide range of clean energy technologies to power rapid economic development, save its cities from suffocating air pollution, and secure its energy future beyond limited domestic resources, Trembath writes.

Reuters/File

Last month, President Obama returned from India, where his administration made progress negotiating towards bilateral cooperation on civilian nuclear power and solar panel trade. The negotiations will make it easier for companies in both countries to deploy nuclear and solar technologies, in addition to renewing support for clean energy RD&D collaboration between the two nations.

“America can be India’s best partner,” President Obama told an audience in New Delhi, echoing sentiments he expressed late last year in China. Obama said the recent energy agreement with China “shows what’s possible when we work together on an urgent challenge.”

The optimistic and diplomatic language Obama has displayed lately actually marks a major evolution in his thinking. Just a few short years ago, the President was framing clean energy innovation as a Cold War-style race for jobs and technologies, hinting that competition and even isolationism could trump cooperation.

President Obama called Asia’s investments in clean energy a “Sputnik moment” in his 2011 State of the Union address. Think tanks, including my own, produced a raft of reports arguing that America risked ceding millions of high-wage manufacturing jobs to its economic competitors. With China spending hundreds of millions to jumpstart export oriented wind and solar industries, America was losing ground and courting economic stagnation.

Today, with the benefit of hindsight, it seems clear that those fears were misplaced. Instead of a cut-throat, zero-sum race to dominate global clean energy industries, all signs point towards an internationally collaborative approach to clean energy innovation.

America’s energy economy is booming thanks to an energy revolution involving oil and gas, not solar and wind. China, by contrast, bet on a wide range of clean energy technologies to power rapid economic development, save its cities from suffocating air pollution, and secure its energy future beyond limited domestic resources.

Today, China has moved to the forefront of virtually every clean energy industry, building dozens of next-generation nuclear plants, first-of-kind coal plants capable of capturing their carbon dioxide emissions, and assuming a dominant role in the global solar manufacturing industry. India is following in China’s footsteps, embracing an all-of-the-above approach that includes everything from distributed solar for rural villages to large coal plants to next-generation nuclear power facilities. The story is much the same in other emerging economies like Brazil, South Africa, and Saudi Arabia.

If there was indeed a clean energy race to be won, America was destined to lose it. The idea that wealthy economies like ours would develop clean energy technologies on our own and then make a fortune selling them to developing economies turns out to have had it exactly wrong.

Transitions to new energy technologies have almost always occurred in lock-step with major increases in energy consumption. The transition from wood to coal for heating, cooking, and mechanical power occurred as energy use soared during the Industrial Revolution. New demand for road and air transport drove the transition to oil as the world’s primary transportation fuel in the early decades of the 20th century. And robust growth in electricity consumption made it possible for the United States to shift twenty percent of its national electricity generation to nuclear power in the decades after World War II.

As such, “technology transfer” is as likely to move from developing to developed economies as the other way around. Great Britain developed the first commercial applications of the steam engine and railroads as well as early breakthroughs that led to electrification, but it was Britain’s former colony, the United States that modified those technologies for mass consumption.

Those developments marked the beginning of Britain’s decline and the United States rise as the world’s preeminent economic power. Yet it is hard to argue that Britain suffered. The UK too saw massive gains in economic output and well-being thanks to the mass commercialization of new energy technologies that it had initially developed in the United States.

The same could be true in the case of clean energy. Losing the clean energy race could, ironically, end up being a boon for America’s future economy. Any low-carbon energy technology capable of scaling in China or India or South Korea, where expensive energy is not an option, would be a boon for America’s economy and environment, irrespective of whether a single job was ever created producing it in the United States.

That's because the benefits of cheap clean energy to the broader economy simply dwarf those that would be created in the energy sector itself. Look no further than America’s own shale gas revolution, which has bestowed $100 billion annual stimulus to Americans in the form of lower electricity prices alone and sparked a mini-resurgence of manufacturing in the United States, as cheap energy prices domestically outweigh the benefits of outsourcing jobs in search of cheap labor.

The macro-economic benefits of the collapse of global oil prices, meanwhile, brought on in significant part by the enormous increase in US production of non-conventional oil, could range as high as a full percentage point in global annual economic growth over the next several years.

If the shale revolution shows us anything, it is that the economic benefits of energy technology revolutions are broadly distributed, rapidly spilling over to every sector of the global economy and not confined to the particular industries that produce energy technology.

That doesn’t mean the United States should stop investing in energy innovation. There will be ample opportunity for American firms and workers to profit from a global energy economy that will double or triple over the next several decades.

But success for the US, China, and other emerging economies like South Korea and South Africa will more likely come from collaboration, not competition. Charles Kenny of the Center for Global Development called this dynamic the “cooperative advantage” (as opposed to the “competitive advantage”), and it will increasingly be the profile of post-globalization growth and innovation.

Today, America’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the Chinese Academy of Sciences are working closely together to demonstrate next-generation salt cooled nuclear reactors in Shanghai. Duke Energy and Tsinghua University are working to demonstrate a gas-cooled reactor in the Shandong province. Shenhua in China and Southern Co. in the United States are building the first US coal plant capable of capturing carbon in Mississippi. US engineered solar panels are manufactured by firms like Suntech in Wuxi and Trina in Changzhou and deployed in large plants from Latin America to the Middle East. Devon Energy, a pioneer in the US shale gas revolution, has been purchased by Sinopec, a Chinese firm and is now working to crack the shale gas code in the deserts of Northern China.

Clearly, it would be foolish to count the United States, blessed with world leading universities, national laboratories, scientists, engineers, entrepreneurs, and venture capitalists, out of the global effort to develop clean energy technologies capable of powering a prosperous world of nine billion people. But it is equally foolish to presume that most of the new energy technologies that will power the 21st century won’t be developed in close collaboration with the non-OECD nations that will dominate the global economy over the coming decades.

Alex Trembath is a senior analyst at The Breakthrough Institute, an energy and environment think tank based in Oakland, Calif.