Central Asia’s pipeline politics: a quest for energy independence

Caught between superpowers Russia and China, can Central Asia's "stans" exert their independence amid a changing energy landscape?

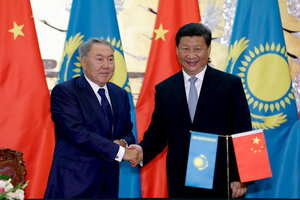

Chinese President Xi Jinping (R) shakes hands with Kazakhstan President Nursultan Nazarbayev during a signing ceremony at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China August 31, 2015.

Lintao Zhang/Reuters/File

Global energy is undergoing tectonic shifts.

Strong US oil and gas production has moved the locus of supply westward, while advanced efficiency and alternative energy have curbed demand across the developed world. The decades-old energy interdependency between Russia and Europe has soured. Moscow, rattled by a one-two punch of low oil prices and Western sanctions, now looks eastward for new customers and partnerships. China’s economy continues to be among the most energy hungry, despite its recent economic slowdown.

Caught quite literally in the middle of it all is Central Asia.

The heart of the Asian continent has long been a hub of energy production and transportation. But even after the fall of the Soviet Union transformed the five Central Asian republics into independent states, Russia’s pipeline policies ensured the world’s largest nation continued to dominate the region’s energy market. In recent years, however, Russia’s firm grip loosened, and China’s growing energy needs prompted Beijing to look west toward “the stans” of Central Asia. Oil and gas pipelines now crisscross the region between China and Russia, both jockeying for geopolitical control.

Now at least one well-positioned producer is attempting to forge a new path that might help it excise itself from the superpowers that have long dictated how their energy is produced, transported, and sold. Turkmenistan, home to the world’s sixth largest natural gas reserves, announced last week it would finally begin construction on a $10 billion pipeline that would transport coveted gas resources to emerging markets in India and Pakistan. Meanwhile, the region’s other energy producing countries are also looking for new markets as a way to avoid dependence on any one single purchaser.

“Central Asia’s move to China was a move towards diversification to begin with, away from Russia,” says Edward Chow, senior fellow in the energy and national security program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “That China’s role has developed to such an extent that the countries now need to rebalance, is rather natural.”

The Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline has been presented as insurance against a prolonged economic slowdown in China, and as a way for Turkmenistan to exert leverage over the world’s third largest energy market. Nevertheless, many experts have raised doubts over whether the project is feasible. A lack of resources, inflexible investment conditions, and an unstable transit route through Afghanistan continue to jeopardize its future. Instead of a realistic step towards diversification, the attempt to pivot away from China is an act of desperation by a country anxious to avoid economic domination by its neighbor, experts say.

“I’m very skeptical [about TAPI]; I don’t think it will be built,” says Dr. Luca Anceschi, lecturer in Central Asian studies at the University of Glasgow in Scotland. “But that doesn’t mean they don’t need it. The more they insist [on building TAPI], the more vital it has become.”

Turkmenistan's golden statues

Of Turkmenistan’s three primary natural gas customers, two are already showing signs of waning or redirected demand. Since 2009, Russia’s state-owned gas giant Gazprom has steadily reduced its imports from Central Asia. Iran, which imports a relatively small amount of Turkmen gas to begin with, will likely rely less on Central Asia as easing Western sanctions revive its domestic industry. That leaves China – Turkmenistan’s No. 1 gas customer – which plans to import around 65 billion cubic meters (bcm) from Turkmenistan by 2020, according to statements by the China National Petroleum Company (CNPC).

By 2025, Turkmenistan could be entirely dependent on the Chinese market, says Dr. Anceschi. That’s a frightening prospect for a country whose economy and political system depend on natural gas revenue. Many Asian gas contracts are linked to the price of oil, so global gas prices are largely following oil’s downward spiral. Meanwhile, China’s economy looks shakier than ever before, casting some doubt on just how energy-hungry the world’s most populous nation will be in years to come.

Turkmenistan is perhaps most famous for its autocratic government, considered by watchdogs to be among the most repressive and corrupt in the world. The late leader Saparmurat Niyazov, known colloquially by the title he bestowed upon himself, “Turkmenbashi”-meaning the father of all Turkmen, ruled from 1985 until his death in 2006.

Turkmenbashi boasted of a formidable personality cult, and to this day a golden statue of the leader towers over the country’s capital Ashgabat, rotating continuously to ensure it always faces the sun. While some believed Mr. Niyazov’s death might bring a new era of openness and democracy, analysts say a repressive regime remains in place nearly a decade later by his successor, current president Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov.

“They [the Turkmens] are focused on resources to lubricate the corruption and bribery that are part of their political system,” Anceschi says.

Meanwhile, the tradition of erecting golden statues has also been passed along. In May, officials unveiled a gold-leaf effigy of Mr. Berdymukhamedov mounted on a horse.

Still, many world leaders appear more concerned with the country’s substantial natural resources than with its form of government. Turkmenistan’s 265 trillion cubic feet of natural gas reserves has prompted even the US government to encourage businesses to reach out to a country where private land ownership is prohibited and most industries are state-owned.

The neighbors

Turkmenistan isn’t the only resource-rich Central Asian country looking for new markets.

Kazakhstan, Central Asia’s other major natural gas producer, has used its fossil-fuel wealth to build an improbably postmodern metropolis in the middle of a desert. Astana, its capital, is home to a cluster of flashy shopping malls, artificial beaches with sand imported from the Maldives, and a spattering of its own showy statues, earning for itself the nickname “The Dubai of Central Asia.”

The country’s president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, has ruled unchallenged since 1989, when it was still a Soviet Republic. Meanwhile, most of his opponents have been jailed or forced to flee the country, which has drawn the longstanding ire of international transparency and human rights groups.

Kazakhstan’s economy is more diverse than Turkmenistan’s, putting it in a much less precarious position. Still, the government is wary of becoming too dependent on China, especially as Kazakhstan’s eastern neighbor increases its share of the country’s oil exports. China’s oil imports from Kazakhstan hit a record high in 2013, increasing 14.09 percent that year, according to the Chinese press. That same year, Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Kazakhstan and signed energy deals worth $30 billion.

“For Kazakhstan, the main concern is to maintain secure and diversified oil exports. Kazakhstan has worked hard to diversify its oil export routes, building pipelines to both China and European markets via Russia,” says Alex Nice, a research analyst covering Russia and Central Asia for the Economist Intelligence Unit.

“But the government is well aware that this is a delicate balancing act. They do not want their energy sector to become too dependent on China. Until recently [Kazakhstan] resisted allowing Chinese firms to invest in major Caspian energy projects,” Mr. Nice continues.

Diversification is also a concern for the autocratic government of Islam Karimov in neighboring Uzbekistan. Nevertheless, today there are few viable alternatives to China and Russia for the home of the ancient Silk Road trade route.

“We haven’t seen any breakthroughs in opening the investment climate in Uzbekistan from countries other than Russia, and perhaps India. But it’s an opaque country and the decision-making is hard to fathom,” says Mr. Chow.

Eyes toward India

Fear of dependence on a single market, ubiquitous across the region, is likely due to the countries’ past experience with Russia, experts say.

"The worry for Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan is that China's monopsony power means that it can dictate prices, reducing export earnings,” says Mr. Nice. “Russia has done this in the past to Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, and the governments are eager to avoid being dependent on a single consumer again.”

India, whose energy consumption grew by 7.1 percent last year, has been seen as a potential counterweight to China in the region. In July, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited both Central Asia and Russia for the first time, and energy was high on his agenda.

Still, it’s unlikely that India will be able to replace China’s role in the region within the next 10 to 15 years, experts say.

“India has been keen to build a presence in the Central Asian energy markets,” says Nice, and the governments involved with TAPI are reluctant to give up on the project despite the obstacles. “But, at present, it’s difficult to see India and Pakistan playing a major role there.”

Chow agrees:

“They are going to have a ceremony, they are going to throw some dirt around, but there will be no TAPI,” he says.

Another potential route away from China could be the Trans Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP), which began construction in Turkey in March. Once completed, TANAP would be the backbone of the European-backed southern gas corridor, which has long aimed to reduce Europe’s energy dependence on Russia.

While the project would originally transport gas from resource-rich Azerbaijan, many have suggested that it could eventually reach across the Caspian Sea and transport gas from Central Asia, allowing Kazakh and Turkmen gas to reach southern Europe. In November 2014, state-owned gas company Turkmengas signed an outline deal with Turkey to supply gas to TANAP.

Even so, these projects are still in their initial phases. Until they become a reality, the region’s regimes must continue to maneuver between their powerful neighbors.

“The [Central Asian] states have been very good at juggling the big states around and juggling them against each other, and they will continue doing that,” says Anceschi.