Kicked out of kindergarten: How do elementary schools discipline?

Districts around the country are looking for ways to keep young children with behavior problems in class.

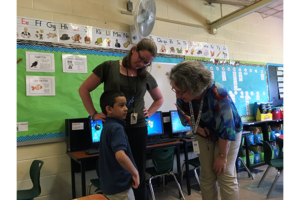

Relationships are at the core of what makes climate work, said O’Brien Principal Lesley Morgan-Thompson, shown at right, with Assistant Principal Corrie A. Schram and a first-grade student.

Sarah Gonser

PHILADELPHIA

When Heather Kiausas was seven weeks pregnant, one of her third graders punched her in the stomach.

Ms. Kiausas, an elementary school teacher with seven years of experience teaching in Philadelphia public schools, had up until then handled the child’s behavior issues – on that day, refusing to complete his work, getting out of his seat, and distracting classmates – by following school protocol: first talking with the student, then recess detention, then calls home, and eventually pink slips to document extreme behavioral problems.

After the punching incident, however, her school principal took discipline to the next level and suspended the boy for several days. Much later, Kiausas learned what might have been behind the punch. “There was a lot of trauma happening at home [for the student],” she writes in an email. “But we were not aware of these issues until months later, after the student was placed in another classroom.”

Incidents like this – and the progression of disciplinary steps that culminated in removing the child from school without addressing underlying problems at home – have prompted Philadelphia and districts across the country to take a hard look at student discipline. So far, Philadelphia has banned suspensions of kindergartners and hopes to do the same for first and second grade students soon. Other districts around the country and even entire states, such as Connecticut, are also banning suspensions and expulsions in the early grades, a practice that research shows disproportionately affects black and Hispanic boys and neglects to take into account other crucial issues impacting a child, such as trauma at home.

Last school year, the School District of Philadelphia suspended 5,667 children under the age of 10, including kindergartners through third graders. Of the district’s 134,041 students, 50 percent are black and 20 percent Hispanic.

Acknowledging the long-term harmful impact of kicking young children out of school, the district revised its Student Code of Conduct last summer to ban suspending kindergartners unless their actions resulted in serious bodily injury. Since then, however, some say the needle hasn’t moved much. “It’s fair to say that young kids are still suspended in Philadelphia in violation of the policy,” says Harold Jordan, senior policy advocate for the American Civil Liberties Union of Pennsylvania. “The district administrators have not come through with implementing the new policy, even when it comes to kindergarten.”

Not so, says Karyn T. Lynch, the district’s chief of student support services. “We’re projecting that we’ll see substantial differences this year [in the number of kindergarten suspensions] compared to last year. In general, we’re encouraged, we think we’re moving in the right direction,” Ms. Lynch says. “It’s important to see this in context of the work that’s been done in advance of this recommendation. It was not a decision we made easily, or without having the necessary climate and framework in place.”

Across the country, disciplining children by kicking them out of school, referred to as exclusionary discipline, affects kids as young as 3 years old. In 2014, the US Department of Education reported 5,000 preschoolers were suspended at least once, and 2,500 preschoolers were suspended more than once.

Research shows that when young children, many of whom are still learning classroom coping skills, are pushed out of school early and repeatedly, the impact can be irreversibly damaging. According to a Department of Education policy statement, children suspended in the early school years are 10 times more likely to drop out of high school, experience academic failure and grade retention, hold negative attitudes about school, and face incarceration, than those who are not.

Philadelphia's ban on kindergarten suspension is a positive step, says Mr. Jordan, though he noted that it remains a work in progress. Overall, however, he says he has seen “a lot of good things happening in the district,” including the district’s focus on reducing exclusionary discipline in middle and high school. “In the later grades, I think we did not lag behind the rest of the country [in changing disciplinary policy]. But we are late to the game when it comes to talking about, much less addressing on a policy front, early childhood exclusion."

Banning suspension in early grades

The most comprehensive effort to eliminate exclusionary discipline for young children is unfolding in Connecticut. In 2015, the state passed legislation banning the suspension of children from preschool through second grade unless it is first determined at a hearing that the child’s behavior is of a violent or sexual nature that endangers others.

“In Connecticut, they didn’t just pass a law; they passed a very nuanced and detailed law,” says Jordan. “It’s comprehensive and savvy with a lot of safeguards, much more detailed than what districts usually do." Another distinguishing characteristic of Connecticut's effort is that the state provides supports to its school districts, and to the agencies that are expected to support them in implementing the policy, rather than relying on individual school districts to organize and fund the supports needed.

Connecticut's Department of Education reports that preschool through second-grade suspensions and expulsions have dropped by nearly one third since the 2014-15 school year – from 2,365 children then, to 1,674 last school year.

One Connecticut elementary school in which suspensions have dropped into the single-digits is the Robert J. O'Brien STEM Academy in East Hartford. O’Brien is classified as a high-poverty elementary school, with just over 60 percent of its students eligible for free or reduced-price meals. Approximately 50 percent of its students are Hispanic, 36 percent are African American, and less than 10 percent are white. Five years ago, O’Brien reported 194 suspensions, including nearly 32 kindergarten suspensions. This year, with one month left before summer break, the school had just six suspensions, none of which involved kindergartners.

This sea change in discipline came about via a transformative cocktail of state-allocated money, district guidance, staff training, and time. “We didn’t exactly have a zero tolerance policy at the time, but the expectations for school staff was that if kids did certain things, they would simply be suspended,” says O'Brien Principal Lesley Morgan-Thompson. “So for us it was all about changing that approach. This took multiple years.”

Getting control of the classroom

To begin the process of reversing the school’s suspension rate, Ms. Morgan-Thompson knew her teachers needed stronger classroom management skills. Following guidance from the district, she immediately enrolled her teachers in training that would help them gain control of their classrooms. To get ready to help students in dire need of support, teachers took a summer course in Life Space Crisis Intervention, a program that trains educators to turn crisis situations into learning opportunities. “We honestly just didn’t have the skills to help our most impacted children,” says Morgan-Thompson.

In spite of these interventions, many teachers at the school still viewed suspensions as a valuable disciplinary tool and questioned their ability to keep students under control without it. That dilemma is at the heart of what critics maintain is an argument against banning suspensions: If children aren’t firmly disciplined, how will teachers control the classroom learning environment?

Banning suspensions in the early grades is not about eliminating interventions, says the ACLU's Jordan. Instead, it is about training school principals, and teachers, to use alternative methods for handling difficult situations. First, he said, school staff must be able to figure out the root cause of the problem, then they can work together to map out a reasonable solution.

In spite of all the training teachers received, Morgan-Thompson says a midyear audit two years ago revealed that just one third of teachers rated student behavior at O’Brien as under control in classes and common spaces. “At that point, they felt behaviors were bad and they had very few options to deal with them. We were working hard to reduce suspensions, so there were just very few options for what they could do to deal with disruptive behavior,” says Morgan-Thompson. “Teachers need to be able to teach, students need to be able to learn and teachers didn’t feel that was happening.”

That’s when she began asking her staff to enroll in district-offered climate and restorative practice training. “This was about giving teachers tools to know how to work with kids, emphasizing that relationships are at the core of what makes climate work,” says Morgan-Thompson.

On the latest midyear audit, said Morgan-Thompson, 73 percent of O’Brien teachers rated student behavior as under control.

Research on the negative impact of exclusionary discipline on young students is clear, said Dianna R. Wentzell, commissioner of education for the Connecticut State Department of Education. “When people talk about the school-to-prison pipeline, it begins with children’s first experience of school. Suspensions and expulsions create academic deterioration, disconnection, and disengagement for our kids,” says Dr. Wentzell.

However, when teachers are given the tools to handle student behavior in ways that de-escalate difficult situations, and teach students how to regulate their own emotions and behavior, says Wentzell, the outcome for children is entirely different.

This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Read more about race and equity and early education.