On college campuses, planning for a post-Millennial future

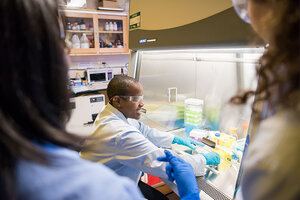

Naomi Mburu works in a lab with her research mentors at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, in March. Ms. Mburu, who graduated in the spring, is the university’s first Rhodes Scholar. She is now pursuing a PhD in nuclear engineering at Oxford University. While at UMBC, she was both a Meyerhoff and Goldwater Scholar, initiatives that aim to support diversity in STEM.

Marlayna Demond/ University of Maryland, Baltimore County

Baltimore

School pride is strong on the suburban campus of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County – and not just because of a history-making basketball upset last year.

UMBC, and its president, Freeman Hrabowski, have earned national recognition for their commitment to racial diversity and the high number of masters and doctoral graduates of color here. The school produces more black graduates with a combined MD-PhD than anywhere else in the country.

UMBC is one of a few campuses that have prioritized student diversity as a core value, says Adrianna Kezar, professor of higher education at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. And that distinction may carry more weight as racial diversity rises in the United States.

Why We Wrote This

Demographic shifts in the United States mean that students live and learn differently than they did 50 years ago. One college offers a model for keeping up with the changing needs of a new generation.

A new report from Pew Research Center shows that the “post-Millennial” generation, currently between the ages of 6 and 22, is the most racially diverse ever. Its oldest members are also enrolling in college at the highest rates in history. The shift spotlights the changing values of a college degree across diverse communities in the US – and raises pressing questions for how colleges can accommodate their transforming student bodies.

“Everything that we do at the center of the institution needs to be rethought,” says Professor Kezar. “If the new demographics of the students are wholly different and the majority of our students are not like those we've had in the past, how do we relook at the primary functions that we have so that they have support?”

This new cohort of students looks a lot less white because of rising enrollment rates especially among Black and Latino communities, says Richard Fry, a senior researcher at Pew Research Center. One key contributor: A bigger proportion of Latino students were born in the US, a fact that correlates with higher academic performances in grade school.

Building support

Sylvia Anokam is a fourth-year student at UMBC. Her parents immigrated from Nigeria and both are college educated. They expect the same for her. That trend is growing among her peers – post-Millennials are more likely to live with a college-educated parent than older generations, according to the research from Pew. Ms. Anokam doesn’t identify strongly with any generational group, but she feels optimistic about rising diversity and college enrollment for people her age.

“The more students of diverse backgrounds are entering the school the more work [to make college accessible] is just going to be coming through because ... now there’s more people that we need to advocate for, there’s more people who we need to look out for,” she says.

UMBC’s minority enrollment is 48.6 percent, which matches the proportion of nonwhite post-Millennials overall, according to Pew. For Millennials in 2002, the nonwhite figure was about 39 percent, and for members of Generation X in 1986, it was about 30 percent. The upward trend is similar for college enrollment: About 59 percent of 18- to 20-year-olds who are out of high school are now in college, compared with 53 percent in 2002 and 44 percent in 1986.

Jason Ashe, a black PhD student in psychology, says the diversity at UMBC today has helped him feel “intellectually safe.” The university has a long list of initiatives aimed at empowering students from underrepresented backgrounds, including the federally funded Upward Bound and McNair Scholars programs, which deliver targeted resources for first generation and low-income students pursuing bachelors and doctoral degrees, respectively.

For Blake Hipsley, a senior and McNair Scholar who is white, the program covered half the cost of his GRE test fees. That made a huge difference, the first-generation student says, because, “I don't have my mom tapping my shoulder, paying it for me. I have to pay out of pocket on my own.”

About 25 percent of the university’s enrollment is first generation, says Corris Davis, director of the Upward Bound and McNair Scholars programs.

UMBC also hosts several university-specific efforts to promote diversity, including a soon-to-be-launched program called Transfer Engagement and Achievement Mentoring, or TEAM. The initiative came out of a conversation between a faculty member and Lisa Gray, the school's associate director of diversity and inclusion, after they noticed troublingly low retention rates for black male transfer students.

“It is not okay for us to let any group of students struggle here. We know that if they could get in here they deserve to be here. So it’s on us to make sure we can support them,” Ms. Gray says.

Making diversity the ‘main dish’

Greater integration of faculty, students, and staff is important to the future of college success, says Kezar. UMBC was founded in 1966 – at the height of the civil rights movement – and President Hrabowski's leadership has continued to fuel its social justice mission. As student demographics change, Kezar says colleges will have to make a concerted effort to track how underrepresented students fare – and what interventions can support them.

“Diversity has been treated like a side dish for kind of its entire history in higher education,” she says. “It goes back to your primary function of the leadership team of any effort.”

The same might be true for the workforce once post-Millennials begin to graduate. Plenty of companies want a diverse roster of employees, says Kezar, but so far few seem keen on taking the steps to achieve it.

Racial representation also doesn’t necessarily translate to inclusion. Mr. Ashe, the psychology student, points out that even though he sees substantial diversity at UMBC, he is still on track to be only the third African-American man to graduate with a PhD from his department.

Ashe and Gray both note that more work is needed to propel underrepresented students forward. But while no institution is perfect, they say the efforts by their school could serve as a model for colleges across the US.

“I like to say we have a very beautiful international airport experience for students at UMBC where everybody's coming at you from all different destinations,” Gray says. “But our work now is to create space for them to have some layover time.”

Clarification: This story has been updated to reflect that Jason Ashe's comments about graduates refer to the number of PhD students in his department, and to add Blake Hipsley's race.