Pioneering spirit: How one school helps Latino students tackle AP tests

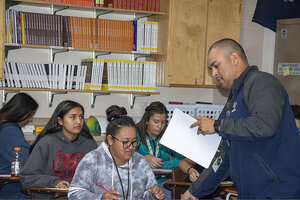

Advanced Placement teacher Ivan Rangel works with students at Del Valle High School in El Paso, Texas. The school’s culture of competitiveness, with a focus on academics, is helping students pass AP tests at a high rate.

Story Hinckley/The Christian Science Monitor

El Paso, Texas

Ivan Rangel weaves among more than 30 desks in his small classroom as he lectures about Confucianism to his high-level Advanced Placement world history class. The ancient Chinese philosopher valued lifelong learning, says Mr. Rangel, and saw education as the only way to “transform the people.” It is self-cultivation that brings success. Nurture not nature.

The class silently stares as their teacher paces among them in his white Converse sneakers. They are absorbing information that will likely be on their AP test this spring. It is a scene common in highly rated high schools in prosperous areas all across the United States.

But this is not one of those prosperous places. To understand Rangel’s lecture, and the value of self-cultivation in education, these students need look no further than themselves.

Why We Wrote This

An increase in Latino teens taking and passing Advanced Placement tests is drawing attention to the schools seeing success. At one in Texas, the focus on self-cultivation could offer a model for educators elsewhere.

The student body here at Del Valle High in El Paso, Texas, is 99 percent Hispanic/Latino. Many students speak limited English, and more than one-third in the school district live below the poverty line. Between classes the hallways roar with students joking with one another in Spanish, and Rangel says many of his students come to school early for WiFi and food – two things they sometimes don’t have at home.

That hasn’t slowed their achievement, however. The students at Del Valle are passing Advanced Placement (AP) tests at a rate that rivals many predominantly white, middle class schools. “Because of all the obstacles we have to overcome, people think of us as trying to catch up,” says Rangel, who has been an AP teacher at Del Valle for almost 10 years. “But I think we’re pioneering.”

In a way, they are pioneers. The number of Hispanic/Latino students passing an AP test in the United States has increased by 183 percent over the last decade – the biggest percentage increase of any demographic. And according to a Monitor analysis of the US Department of Education’s Civil Rights Data Collection, even Hispanic/Latino students at large, mostly minority high schools like Del Valle – those that are often expected to struggle the most – are passing AP exams at rates competitive with white peers.

Del Valle could offer a model for how similar schools can provide their students a strong foundation for higher education. One secret: promoting competition in academics, not just sports.

“The students here are aggressive and relentless about doing well in school,” says Ysleta Independent School District Superintendent Xavier De La Torre. “It’s all about helping kids understand that the trajectory that your life will take is directly tied to how hard you work now, and what you achieve now,” he explains.

Talking point: unequal access

AP classes are rigorous high school courses offered in subjects ranging from environmental science and French to calculus and world history. Students are graded just like other classes, but at year’s end, they usually take an AP test, administered by the College Board. Students score between a 1 and a 5, with high scores earning college credit at many institutions.

More than 2.8 million high school students took an AP test in 2018 – almost quadruple the number of test-takers a decade ago. Proponents of the exams say that this is a testament to AP’s increasing value in higher education: students are more likely to be accepted to college, and then succeed, if they have passing AP scores on their application.

But access to AP classes and AP testing results have long been marred by racial and economic inequities. Mostly African-American and mostly Latino high schools face AP opportunity gaps, created by state and local funding formulas, teacher placements, and most importantly, an expectations gap, says Reid Saaris, founder of Equal Opportunity Schools, a group that helps low-income students of color get access to AP classes.

“[E]qually talented black and Latino students are less likely to be given information about the benefits of AP and how to sign up, are less likely to be encouraged by educators to participate in advanced courses,” says Mr. Saaris. “As a country we need to be talking about that.”

To try to better understand this disparity the Monitor took a closer look at US Department of Education data from highly segregated schools – institutions where 90 percent or more of the students are black/African-American, or 90 percent or more are Hispanic/Latino. The number of these intensely segregated, nonwhite schools has more than tripled over the last three decades. Experts point to AP testing as one of the places to better understand segregation's effects.

Some schools stand out

The Monitor’s analysis of the Civil Rights Data Collection from the US Department of Education shows that large (more than 800 students) and segregated (more than 90 percent of students from one racial category) US high schools produce widely different AP results if sorted by race.

At the 607 large, mostly white schools included in the survey, 18 percent of students on average took an AP exam of some kind at the end of the year. Nine percent of all students passed a test (defined as scoring a 3 or higher, a level at which colleges begin to consider awarding credits).

At the 93 large, mostly black/African-American schools surveyed, 10 percent of students, on average, took an AP exam. Only 1 percent of students scored a 3 or higher on a test, according to the Monitor analysis.

At the 202 large, mostly Hispanic/Latino high schools in the Civil Rights Data Collection, 20 percent of students took an AP test, on average. Six percent of students passed a test.

This means that Hispanic/Latino students at mostly Hispanic/Latino high schools are more likely to take an AP test than white students at all-white high schools. Almost all of the Latino and black high schools were “mid-high” or “high” poverty (which means half or more of the students qualify for free or reduced lunch), and fewer than one-fifth of the mostly white high schools had the same designation.

And some largely Hispanic/Latino school districts stood out from the rest – particularly the Ysleta Independent School District of El Paso, Texas, which had five high schools in the top 10 of all 202 large schools with similar demographics. Ysleta’s high schools suggest that poor, minority students have the ability to master the rigors of AP if they are encouraged to take the courses and taught by well-qualified teachers.

During the 2015-2016 school year, the most recent data from the Civil Rights Data Collection, Ysleta’s Riverside, Bel Air, Ysleta, and Eastwood high schools all had AP passage rates above the national average of 22 percent. Del Valle's rate was even higher, with 35 percent of the school’s 1,414 Hispanic/Latino students taking – and passing – an AP course.

The district has a pre-AP track in its nine middle schools, and a curriculum that schedules Algebra I as an eighth grade course, rather than a high school course.

De La Torre says he has focused on recruiting and retaining talented AP teachers since he came on as superintendent four years ago. He requires all AP teachers to attend a summer training in their course areas and he instructs principals to monitor AP teachers’ success in the classroom. In the near future he hopes to start a financial incentive for teachers, giving $5,000 to teachers for each AP class in which 50 percent of students pass the test.

Teachers, counselors, and the superintendent point to the culture of excellence promoted at Del Valle as a reason for its students' success. The resulting competitive atmosphere, says Yasmin Villa, one of Del Valle’s school counselors, is a tide that raises all boats.

“[T]hey know so-and-so is the valedictorian and they push themselves to get to the top,” says Ms. Villa. “I’ve been here for 5-1/2 years, and I’ve never not seen a super-competitive class.”

Eduardo “Eddie” Garcia, Del Valle’s valedictorian, says it’s not a coincidence he and his friends hold the top spots in the class. Their daily lunch conversations, he notes, center around grades and how to do better in school. “It’s fun to compete with each other,” he says.

Eddie’s transcript – he says he’s taken all the AP classes that Del Valle has to offer – will boost his college applications, but it will also make college a financial possibility. Eddie is a few credits short of being a sophomore in college – thanks to passing scores on AP tests and dual-credit classes – which means he can likely graduate in three years and pay one year less of tuition.

“I want to save money by getting my [college] credits in high school,” he says. “I enjoy learning, and being here I get the opportunity to take advantage of that.”

A closer look at gains

The predominantly Hispanic/Latino high schools have seen big improvement in AP passage scores over the last few years. The five top-scoring Ysleta high schools, for example, all had double digit increases between 2009 and 2015.

Some education experts attribute Latino students’ increasing scores to AP Spanish: a test that would be easy for native Spanish speakers. Others suggest students’ improvement is consistent with an overall increase in the number of Hispanic /Latino students. But hundreds of students passed AP math or science at the top 10 scoring Hispanic/Latino high schools (see graph above), and the rate of Hispanic/Latino AP passers is growing at a faster rate than the overall Hispanic student population.

Figures from the College Board show that in recent years the numbers of minorities taking the exam have steadily climbed. In 2007, about 57,000 Hispanic/Latino students sat for a test; in 2017, the corresponding number was about 163,000, an increase of 184 percent. For African-American students this increase was also impressive, from about 14,000 to 30,000 over the same time period, representing a 119 percent rise.

But not all large, segregated African-American and Latino schools share in the the good news. At Belaire High School in Baton Rouge, La., for example, only two of the school’s 1,113 black/African-American students took an AP course in 2015. Neither of them passed. At Bell Gardens High outside of Los Angeles, 916 of the school’s 3,000 Hispanic/Latino students took an AP test – none of them passed. And at Morgan Park High School in Chicago, 286 black/African-American students took an AP course, and none passed.

African-American students also remain underrepresented when it comes to scoring a 3 or higher, compared with white and Latino student populations. Black/African-American teens accounted for about 14 percent of the US high school class of 2017 but they were only 4 percent of the students who passed an AP test, according to College Board figures.

Some education experts have begun to question the value of AP programs. Some schools have decided to cut their AP offerings altogether, such as the eight elite private schools in Washington that announced their decision to do that earlier this year.

But in many cases, these schools have the resources to develop challenging courses on their own. Their graduates are perhaps more likely to receive tutor assistance to raise SAT scores, or experience outside activities, such as world travel, that could bolster college applications. Students at segregated minority schools have fewer such advantages.

“We should focus on APs because the national conversation about black and Latino students trends toward the negative. ‘How do we prevent black students from dropping out?’ Or, ‘How do we prevent black students from going to prison?’ ” says Saaris of Equal Opportunity Schools.

“APs are a way to elevate the conversation away from a deficit framing, away from a talk of all the bad things that could happen to kids, and toward a conversation of all that’s possible when you provide equitable opportunities,” Saaris adds.

Back in Rangel’s AP classroom, with 10 minutes left in the period, Rangel announces that grades from a recent homework assignment are posted on the whiteboard in the front of the classroom, and students are welcome to come look when they finish an in-class assignment.

The students quickly finish their readings and speed walk toward the whiteboard. They elbow and jostle one another to find their own name on the list.

“Erin, what grade did you get?” one students calls to another. It’s difficult to hear Erin’s answer over the other comparison conversations happening around the room, but judging by the column of 100 percents on the grade sheet, it’s likely she did well.