New 'temperate' exoplanet hints at solar system like our own

Astronomers have for the first time made detailed measurements of an exoplanet in the temperate zone around its star. Their conclusion: It looks a lot like a planet in our solar system.

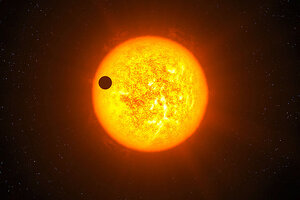

An artist's impression shows CoRoT-9b, the first temperate exoplanet to be measured in detail. Scientists say it is about the size of Jupiter and orbits its parent star at about the same distance that Mercury orbits the sun.

AFP/ESO

Astronomers have discovered a Jupiter-size planet that orbits its host star at a Mercury-like distance – a solar system that begins to look like a topsy-turvy, Alice in Wonderland version of our own.

The discovery has allowed scientists to glean for the first time a wide range of information about an extrasolar planet so relatively distant from its "sun."

It opens the door to detailed studies of gas giants in the temperate zone around stars – the single largest group of exoplanets scientists have found so far, and a class of planets that begins look more familiar to Earth-bound eyes.

The planet, CoRoT-9b, "can start to tell us more about exoplanets which may be more akin to the giant planets in our solar system," writes David Ciardi in an e-mail exchange. Dr. Ciardi is a researcher at NASA's Exoplanet Science Institute, based at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, Calf., and a member of the international team reporting the discovery in tomorrow's issue of the journal Nature.

The planet, which orbits a sun-like star some 1,500 light-years from Earth in the constellation Serpens, was first detected in 2008 by instruments aboard the European Space Agency's COROT satellite. The spacecraft was designed to study the physics of distant stars and to detect any transiting planets in the process.

How it was found

Transiting planets are those that, from the telescope's perspective, pass in front of the stars it observes. When planets can be detected passing in front of or behind their parent stars, scientists can tease out a variety of data, including a planet's physical size, density, key orbital traits, and make basic measurements of its atmosphere.

But the only transiting planets scientists have been able to find are "hot Jupiters" – gas giants circling very closely to their parent stars.

By contrast, another telltale way of finding extrasolar planets – reading the gravitational pull they exert on their partent stars, apparent as a "wobble" – makes it easier to find planets at a range of distances, but it yields less information.

The discovery of CoRoT-9b marks the first time that scientists have successfully used the transit method to detect a planet at such large distances from its host star.

Once the team discovered the event in its data, it turned to ground-based telescopes to ensure it didn't get a false alarm from what is thought to be a nearby binary star system in which one star eclipses the other.

In addition, the team tapped astronomers using the radial velocity "wobble" technique to confirm 9b's existence.

What is CoRoT-9b like?

Using data from these two techniques, the team calculates that the planet is virtually identical to Jupiter in size, but has only about 84 percent of Jupiter's mass and 68 percent of Jupiter's density.

Based on the planet's distance from its sun, the team estimates that the planet's temperature ranges between 160 degrees C (320 degrees F) and minus 20 degrees C. While the daylight temperatures certainly are steamy, they pale compared with those of "hot Jupiters," whose temperatures can reach nearly 10 times that of CoRoT-9b's.

The team also calculates that the gas giant sports a core of heavy elements up to 20 times more massive than Earth. That gives it another Jupiter-like trait; our solar system's most massive planet is thought to have a rocky core up to 15 times Earth's mass.

"This is a normal, temperate exoplanet, just like dozens we already know," says Claire Moutou, an astronomer at France's National Center for Scientific Research's astrophysics laboratory in Marseilles. Indeed, the team notes that these "temperate" Jupiters constitute the bulk of extrasolar planets astronomers have discovered so far.

Still to come: atmospheric data

The team hasn't analyzed the CoRoT-9b's atmosphere yet, a task they can accomplish by when the planet passes in front of the star. This allows them to record the spectral fingerprints of the main gases in the atmosphere. Some possibilities include water, methane, and carbon dioxide.

Yet some details will remain elusive until a new crop of more powerful ground- and space-based telescopes come online, writes Hans Deeg in an e-mail exchange. He is a researcher with Spain's Institute for Astrophysics on the Canary Islands and the lead author of the paper reporting the results.

One feature scientists would like to capture is the planet's so-called secondary eclipse as the planet moves behind its host star. This can yield more information on the planet's atmosphere, including information on how it transports heat and whether it has clouds.

But that requires measurements of extremely faint light from a planet as far from its host star as CoRoT 9-b. It's a feat beyond the capability of today's instruments, he explains.

These sorts of studies on exoplanets at CoRoT 9-b's temperature range await a new generation of 30- and 40-meter ground-base telescopes and the James Webb Space Telescope, scheduled for launch in 2014.