Kepler telescope's astonishing haul: 54 planet-candidates in 'habitable zone'

The Kepler space telescope is designed to look for planets like Earth that could have life. But no one expected it to find 54 planet-candidates at Goldilocks distances from their stars – not too warm or cold for life as we know it – in its first four months of operation.

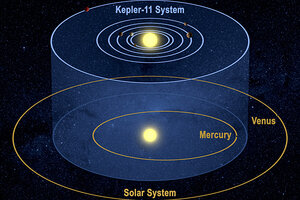

This artist rendering provided by NASA shows a peculiar solar system discovered by the Kepler space telescope. The image shows how five of the planets in the Kepler-11 system would be located within Mercury's orbit in our own solar system. 'We never thought we'd see this many planets that aren't real, real tiny, this close to one another,' one scientist said.

NASA/AP

NASA's Kepler spacecraft has uncovered 54 planet-candidates that orbit within their host stars' "habitable zones" – Goldilocks distances where the star warms the planet sufficiently to allow liquid water to remain stable on its surface.

The potential finds, which must clear an arduous, detailed confirmation process, still fall short of the ultimate goal, finding an Earth-size planet orbiting a sun-like star at Earth-like distances.

But if these candidates pan out as planets, their discovery – and its implications for uncovering many more as time passes – increases the likelihood that life has gained footholds elsewhere in the galaxy.

Five of the 54 candidates are near Earth's size but orbit smaller, dimmer stars that the sun. Others range in size from twice Earth's radius to larger than Jupiter. If these turn out to be planets, researchers speculate that any moons they might have could be habitable, even if the planet itself isn't.

'Milestone discoveries' faster than anticipated

These 54 objects appear on an overall list of 1,235 planet-candidates Kepler has detected during its first four months of operation – a pace significantly faster than even it's biggest supporters expected.

Last March, accomplished planet-hunter Debra Fischer, a Yale astronomer who is not a member of the Kepler team, suggested that Kepler's first year of operation would be dominated by discoveries of star-hugging, Jupiter-class planets, because those would be the easiest to spot. Only after three years of operation would Kepler begin to uncover Earth-scale planets, she forecast.

Instead, Kepler has served up a list of potential planets that includes 68 Earth-sized objects, 288 "super Earths," 662 Neptune-class objects, 165 Jupiter-scale objects, and 19 objects larger than Jupiter.

"I'm amazed to sit here today and see that Kepler reaching the milestone discoveries faster than I anticipated," she said during a NASA briefing Wednesday discussing the results.

A baffling solar system found

The Kepler team also announced the discovery of a six-planet solar system about 2,000 light-years from Earth that is bound to send theorists back to their white boards to squeak out an explanation for the system's unusual configuration.

The six planets orbit their star at a distance that would fall within Venus's orbit around the sun. Five of the planets would easily fall inside Mercury's orbit.

"It is an amazing system," says Jack Lissauer, a member of the Kepler team at NASA's Ames Research Center at Moffett Field, Calif., and the lead author of a paper describing the discovery in the Thursday issue of the journal Nature.

The five innermost "planets are close in, and we never thought we'd see this many planets that aren't real, real tiny, this close to one another," he said. The five range in size from about twice the radius of Earth to slightly more than four times Earth's radius.

The densities the team calculated for the two innermost planets suggest they are a combination of rock, water, and perhaps gas. The three outermost planets of the five, however, are so large for their mass that "a substantial fraction of their volume must be made of hydrogen and helium gases," Dr. Lissauer says.

It's a planetary system "of a type we had no idea existed," he says.

This discovery alone may have been worth the price of admission, suggests Dr. Fischer.

It's "an absolutely staggering result," she says. "With five low-mass planets in the system, this discovery is every bit as momentous as 51 Peg was" – a reference to the discovery in 1995 of the first planet orbiting a sun-like star, 51 Pegasi.

Next step: confirmation

Indeed, 170 of the 155,000 stars Kepler is monitoring appear to be multiple-planet-candidate systems.

Based on the large number of planet-candidates Kepler has uncovered and the small patch of sky it is observing, "the stars around us have a huge number of planets and candidates for us to look at," says William Borucki, the mission's chief scientist. "If we find that Earth-size planets are common in the habitable zones of stars, it's very likely that life is common around these stars."

NASA launched Kepler in March of 2009. The craft is designed to detect extrasolar planets by recording the subtle dimming that occurs as a planet orbits across the face of its host star. This so-called "transit approach" to planet detecting can provide information about a planet's size.

A second approach – the so-called "radial velocity" method – detects a planet by the gravitational tug it imparts to its host star, which shows up as wobbles the star's spectrum. Radial velocity measurements can yield information about the planet's mass.

Kepler's finds are now awaiting confirmation by radial velocity measurements. If the candidates are planets, the radial velocity measurements will help yield the planets' bulk densities and thus a rudimentary idea of their bulk compositions.

Kepler's effort is one the public can join. Fischer explains that the researchers have established Planethunters.org – a website where people can look at graphs of the light output from the stars Kepler is observing and hunt for the telltale signs of a planet candidate. So far, she says, some 16,000 participants worldwide have identified hundreds of "solid" transiting-planet candidates, as well as previously undiscovered eclipsing binary stars.