Solar Flare: A Northern Lights show for North America?

Solar flare - one of the biggest in four years - shot from the sun on Sunday. Scientists predict that a solar flare of this size - and traveling toward Earth - could produce a dramatic light show. Did it?

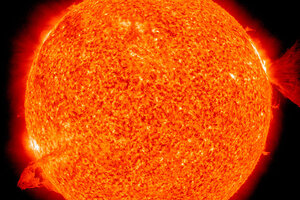

This image of the sun, captured by The Solar Dynamics Observatory spacecraft January 28, 2011, shows nearly simultaneous solar eruptions on opposite sides of the Sun, in this photograph released by NASA.

Nasa/Reuters

A powerful solar flare, hurled into space when superhot gases erupted on the sun Sunday (Feb, 13), might cause a display of the aurora borealis for parts of the northern United States.

The sun unleashed the solar flare Feb. 13 at about 12:30 p.m. EST (1730 GMT) from a sunspot region that was barely visible last week. Since then, it has grown in size to more than 62,000 miles (100,000 kilometers) across — nearly eight times the width of our Earth.

The flare was categorized by the NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center in Colorado as a Class M6.6 and is the strongest solar flare observed in 2011. It could ramp up northern lights displays for skywatchers living in northern latitudes and graced with clear skies.

Such a flare, covering more than 1 billion square miles of the sun's surface (called the photosphere), was described as "moderate" in intensity. Class M flares are stronger than the weakest category (Class C). They are second only to the most intense Class X solar flares, which can cause disruptions to satellites and communications systems and pose a hazard to astronauts in space.

NOAA's Prediction Center has forecast the possibility of additional solar flares from the same sunspot region over the next two or three days.

Sun flares are gas pains

Solar flares appear to be caused by a sudden release of magnetic energy. The flare itself occurs in the solar atmosphere, generating a brilliant emission of visible light, as well as ultraviolet waves and powerful X-rays.

With major flares there is a disruption of radio communications shortly after the eruption. Indeed, Sunday's eruption produced a loud blast of radio waves that was heard in shortwave receivers around the dayside of our planet.

But solar flares also can act as a type of explosion that sends streams of electrons and protons out into space. These electrons, protons and other particles are hurled out of the sun's magnetic field in a wave of electrified gas.

As these electrons and protons come into contact with the Earth's magnetic field and stream toward the magnetic poles, the chance of a collision between these charged energy particles and the rarefied gases of the upper atmosphere increases dramatically, producing a disturbance, or "magnetic storm," in the Earth's magnetic field.

Along with causing additional disruptions to radio communications, a magnetic storm might also prompt a view of the aurora borealis, or northern lights, across parts of the northern United States.

But, predicting space weather can be as difficult as predicting the weather on Earth. So there are no guarantees that you'll see anything.

Earth in the crosshairs

However, Sunday's solar flare occurred near the middle of the sun's disk, meaning that the resultant explosion of electrified particles could be "geoeffective," that is, directed toward the Earth.

So, in essence, our planet was "in the crosshairs" of this solar explosion and would thus increase the chance that an auroral display might result. Ideally, the associated stream of particles could reach the Earth 37 hours after the flare's eruption.

That would correspond to Feb. 15. But this is only an approximation; the actual commencement of a possible magnetic storm could occur many hours earlier or later, so it would be best to check the sky periodically during the overnight hours to assess if any activity is actually taking place.

The prospective zone of visibility can include the northern Rockies, northern Plains, the Great Lakes, northern portions of Pennsylvania and New Jersey as well as all of New York State and New England.

However, if the stream of electrified particles turns out to be less energetic, aurora visibility might be confined to places farther to the north, and nearer to the Canadian border. Conversely, if the particle stream turns out to be stronger than forecast, an aurora might sighted farther south into the central U.S.

Those wanting to try to see any auroral activity should find a dark location with a flat northern horizon and look north. Look for greenish or reddish glows or streamers.

A dark sky also helps. Unfortunately, the moon is currently in a waxing gibbous phase and pretty much will light up the sky until it sets around 4:30 a.m. EST (0930 GMT). The sky will be darker after the moon sets, making it easier to observe whatever northern lights might be visible.

Good luck.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.