Black hole fires beam of energy at Earth while swallowing star

Black hole fires beams at Earth while destroying star: a massive black hole has been discovered devouring a star, causing the star to shoot beams of energy at Earth. The event is thought to occur only once every 100 million years.

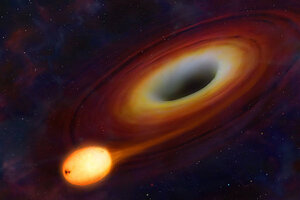

Black hole swallows star: This artist's image provided by the University of Warwick shows a star being distorted by its close passage to a supermassive black hole at the center of a galaxy.

Photo illustration/Mark A. Garlick/University of Warwick/AP

A powerful beam of energy has been spotted blasting out from the center of a massive black hole as it rips apart and devours a star in a rare sight that astronomers say likely happens only once every 100 million years, a new study finds.

When a NASA satellite first detected the intensely bright flash deep in the cosmos, astronomers initially thought it was a powerful burst of gamma rays from a collapsing star, one of the most powerful types of explosions in the universe. But, when the tremendous amount of energy could still be seen months later, they realized something more mysterious was going on.

"This is a really, really unusual event," study co-author Joshua Bloom,assistant professor of Astronomy at University of California, Berkeley, told SPACE.com. "It's now about two-and-a-half months old, and the fact that it just continues on and is only fading very slowly is the one really big piece of evidence that tells us this is not an ordinary gamma-ray burst."

NASA’s Swift Gamma Burst Mission spacecraft first detected the gamma-ray flash, called Sw 1644+57, within the constellation Draco, at the center of a galaxy nearly 4 billion light-years away.

Using Swift observations and others by the Hubble Space Telescope and the Chandra X-ray Observatory, Bloom and his colleagues concluded that the strange activity they were seeing was likely from a star being ripped apart by a massive black hole, rather than the effects of a gamma-ray burst, which typically can only be observed for about a day.

"This burst produced a tremendous amount of energy over a fairly long period of time," Bloom said. "That's because as the black hole rips the star apart, the mass swirls around like water going down a drain, and this swirling process releases a lot of energy."

These findings are published online in the June 16 issue of the journal Science.

Death of a star

Bloom's research showed that the highly energetic and long-lasting X-rays and gamma-rays were produced as a star about the size of our sun was violently shredded by a black hole a million times more massive.

But, what makes this a rare event is that this particular black hole has not been eating up matter around it like some other active black holes in the universe, Bloom said. In fact, the researchers sifted through historical records of that region of the cosmos and could not find evidence of previous long-lived X-ray or gamma-ray emissions.

"This event was not the act of gobbling lots of gas, but instead was a sort of impulsive thing," Bloom said. "This sort of thing could happen at the center of any galaxy, but the rate at which this happens is very low. It's sort of a one-off event that really shouldn't happen again."

Astronomers were even luckier to have been able to witness the event with such detail and clarity, since the jet of X-rays and high-energy gamma rays were punched out along a rotation axis that placed Earth in the eye of the beam.

“The best explanation that so far fits the size, intensity, time scale, and level of fluctuation of the observed event, is that a massive black hole at the very center of that galaxy has pulled in a star and ripped it apart by tidal disruption," said Andrew Levan of the University of Warwick in the U.K., lead author of a companion piece that was also published in Science. "The spinning black hole then created the two jets, one of which pointed straight to Earth.”

A lucky view

Essentially, astronomers here on Earth are looking down the barrel of the jet, witnessing an event which is likely to happen about once in 100 million years in any given galaxy, Bloom said.

"This is part of the special nature of the event," he said. "What we have is a geometrical rarity on top of an already rare event. I would be surprised if we saw another one of these anywhere in the sky in the next decade."

The astronomers suspect that the gamma-ray emissions began on March 24 or 25, at a distance of about 3.8 billion light-years away. And while they are still detecting activity from this event, Bloom and his colleagues estimate that the emissions will fade over the next year.

And while this may be an incredibly rare event, it does help astronomers further understand how black holes grow.

"I think this adds another piece of evidence that black holes grow organically by gobbling not just other black holes during mergers of galaxies, which is one of the ways people think black holes grow, but they also grow by eating up their surroundings in the form of gas and stars," Bloom said. "If this picture is right, black holes grow in many different ways. It addresses some unanswered question in astrophysics: these infants aren't just feeding on one baby product, namely merging with brethren, but they're gobbling up different types of foodstuffs."

You can follow SPACE.com Staff Writer Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.