NASA's Dawn satellite has reached the asteroid belt. First stop: Vesta.

Vesta and Ceres, the two largest objects in the asteroid belt, have mystified scientists for centuries. With NASA satellite Dawn on final approach to Vesta, the wait is almost over.

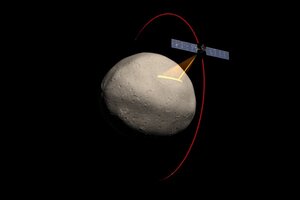

NASA produced this computer-generated image of Dawn gathering data from Vesta. After years in space, Dawn is finally drawing close to Vesta, which it will orbit for a year as scientists gather data. When it finishes with Vesta, Dawn will continue on to Ceres, the largest body in the asteroid belt.

Courtesy of JPL / NASA

After four years and 1.7 billion miles – including two swings around the sun – NASA's Dawn spacecraft is on final approach to Vesta, an object expected to provide an unprecedented glimpse into the early years of the solar system.

Dawn, with its futuristic ion-drive engine, is just over 100,000 miles from its target – closing in at the stately pace of about 260 miles an hour, relative to Vesta's orbital speed.

The craft is scheduled to take up its orbit July 16 and spend a year at Vesta. Then it heads for a year-long visit to Ceres, slated to begin in 2015, said Robert Mase, Dawn's project manager, during a final-approach briefing Thursday.

Both objects call the main asteroid belt home. The belt encircles the sun between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter.

Dawn is the first NASA mission designed to visit and orbit two objects with the same spacecraft.

As planetary scientists crafted their to-do list for a visit to Vesta, it became clear that "this tiny world has huge importance," says Carol Raymond, the mission's deputy lead scientist and a researcher at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. "Vesta is a window into the early origins of our solar system and the terrestrial planets."

In some ways, the notion of looking at asteroids and their tailed cousins, comets, as "windows on the early solar system" has become something of a cliché – an early hope that has been fulfilled in some cases, but not in others, as researchers have learned that some of these objects have been heavily altered by their billions of years orbiting the sun.

But researchers say they have strong reason to believe Vesta and its larger sibling, Ceres, will live up to their billing. Both represent objects that could have become planets in their own right, had Jupiter's rapid growth and quickly changing gravitational field not interfered.

Each represents an intriguing snapshot of planet formation taken at different stages of growth, holding clues to the processes that built planets – and stymied the formation of others – during the first 10 million years of the solar system's 4.6 billion-year history.

What is Vesta?

Vesta was discovered in 1807. Although its shape isn't uniform, the object averages about 329 miles across. It's the second most massive object in the main asteroid belt, after Ceres.

Ground-based and Hubble Space Telescope observations have uncovered what appears to be a vast crater some 290 miles across, near Vesta's south pole. The rim rises from 2.5 to 7.5 miles above the surrounding landscape, while the floor lies some 8 miles below the rest of the landscape and hosts a central peak that vaults 11 miles above the crater floor.

The impact is thought to have spawned a family of asteroids known as V-type asteroids, as well as untold numbers of meteoroids, many of which have landed on Earth.

Indeed, one in every 20 meteorites that scientists find come from Vesta, says Christopher Russell, a planetary scientist with the University of California at Los Angeles and the leader of the international team of researchers behind the mission.

Analyses of these meteorites have led researchers to conclude that Vesta formed about the same time Jupiter did. Jupiter is widely thought to be the first planet that grew from the disk of dust and gas that surrounded the early sun.

The composition of those Vesta meteorites also suggests that at the time its development was arrested, Vesta already had started to experience enough heating from its interior – and from impacts by other objects – to begin the process of separating dense materials from lighter materials. Like the iron in Earth's core, the heavier, denser materials gravitated toward Vesta's center, while lighter ones rose toward the surface.

That geophysical separation of materials within Vesta has prompted many scientists to promote it from asteroid to protoplanet.

What paused Vesta's development before it could mature from protoplanet to planet? One leading suspect is Jupiter, whose relatively rapid growth and gravitational influence on the neighborhood triggered a bumper-car-like free-for-all in the asteroid belt.

"It would have grown into a planet had it been allowed to continue," Dr. Russell says.

These are among the processes scientists hope to confirm once Dawn arrives next month.

Dawn's next destination: Ceres, queen of the asteroid belt

Ceres, by contrast, is now considered a dwarf planet, a step up in rank from a protoplanet.

Ceres is some 600 miles across and accounts for roughly a third of the mass of all the objects in the main asteroid belt. And unlike Vesta, Ceres is spherical.

Ceres, too, appears to have undergone partitioning of its interior by the density of the materials it contains. Like most of the moons orbiting the gas giants, Ceres is thought to have a rocky core covered by an icy mantle – and, like Saturn's moon Enceladus, may host a mini sea under the ice.

With Vesta and Ceres nothing more than fuzzy blobs from our best telescopes, it's little wonder planetary scientists are eager to visit these objects via an orbiting spacecraft. What they think they know now about these two objects is built on models and out-of-focus images.

Dawn is giving scientists "an unprecedented opportunity to spend a year at a body we really know nothing about," Dr. Raymond says.