Why does Mars Curiosity rover have a laser raygun?

NASA's Mars rover, Curiosity, is armed with a laser to zap rocks, not Martians. The laser can vaporize rocks at a distance of 23 feet.

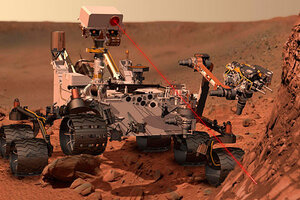

This artist's conception depicts the rover Curiosity, of NASA's Mars Science Laboratory mission, as it uses its Chemistry and Camera (ChemCam) laser.

REUTERS/NASA/JPL-Caltech

Yes, NASA's Mars rover has a laser gun.

But there are no plans for Curiosity to zap Martians.

This cool little laser – and it is tiny – is designed to vaporize a pin-head sized area of Martian rock. The laser heats up the rock, and turns it into a glowing ionized gas. It's part of an instrument on the rover Curiosity known as the "ChemCam." The ChemCam observes the flash of vaporized rock and analyzes the spectrum of light to identify the chemical elements in the rock. The laser has a range of about 23 feet.

Here's how NASA describes the process:

"The pinhead-size spot hit by ChemCam's laser gets as much power focused on it as a million light bulbs, for five one-billionths of a second. Light from the resulting flash comes back to ChemCam through the instrument's telescope, mounted beside the laser high on the rover's camera mast. The telescope directs the light down an optical fiber to three spectrometers inside the rover. The spectrometers record intensity at 6,144 different wavelengths of ultraviolet, visible and infrared light. Different chemical elements in the target emit light at different wavelengths."

If the ChemCam analysis proves interesting, the Curiosity rover can move in and drill or scoop up an actual sample of the rock. The pulse laser can also be used to "dust off" an interesting rock formation with a series of short bursts.

NASA officials note that earlier Mars rover missions have been unable to identify some of the lighter elements, such as carbon, oxygen, hydrogen, lithium and boron. They note, for example, that a Mars mission in 2005 looked at an outcrop called "Comanche," and it took years of analyzing indirect evidence before the team could confidently infer the presence of carbon in the rock. ChemCam can identify carbon with one shot.

The idea for putting a laser on a Mars rover is traced by NASA back to 1997. At the time, Roger Wiens was a geochemist with the US Department of Energy's Los Alamos National Laboratory, and was working on an idea for using lasers to investigate the moon. Wiens visited a chemistry laboratory building where a colleague, Dave Cremers, had been experimenting with a different laser technique. Cremers set up a cigar-size laser powered by a little 9-volt radio battery and pointed at a rock across the room.

"The room was well used. Every flat surface was covered with instruments, lenses or optical mounts," Wiens recalls in a NASA web site. "The filing cabinets looked like they had a bad case of acne. I found out later that they were used for laser target practice."

The ChemCam fits into Curiosity's mission to understand the chemistry of Mars and is "an important next step in addressing the issue of life in the universe," John Grotzinger, a planetary scientist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, Calif., told The Christian Science Monitor's Pete Spotts recently.

The Mars mission, launched Saturday Nov. 26, aims to reconstruct from the planet's minerals the history of water, a liquid essential to life as researchers currently understand it. As Spotts wrote:

"The record of environmental conditions early in the planet's history, when it was thought to have been at its wettest, is believed to be written in the layers of rock the Mars Science Laboratory's team has identified in Gale Crater, a 100-mile-wide impact feature with a mountain that soars three miles high from the center of the crater's floor.

After an eight-and-a-half-month cruise, a nail-biting final descent aims to place the six-wheeled robotic chemist squarely in the crater.

If all goes well, Curiosity will initially spend 98 weeks traversing some 12 miles or more – driving, drilling, then analyzing the drill tailings to help build a picture of the environments that existed at the location as the planet made the transition from a wet planet, to a periodically wet planet, to the desiccated orb humans are visiting today."