Scientists unravel mystery of humongous space explosion

Great Eruption of Eta Carinae, a massive star some 7,500 light-years away that suddenly lit up the night sky for a decade beginning in 1838 is one of the most studied objects in the Milky Way. But it continues to puzzle astronomers.

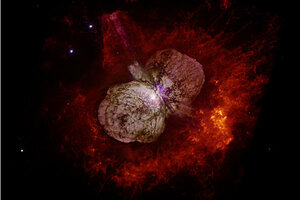

This image captured by the Hubble telescope shows Eta Carinae one of the most massive stars in our galaxy. The star erupted about 160 years ago, creating a billowing pair of gas and dust clouds, each moving outward at about 1.5 million miles per hour.

N.Smith & J.Morse/Courtesy of NASA

An explosion in space first seen in the 19th century was apparently colder than before thought, throwing a new mystery into what may have triggered it, researchers say.

The cosmic eruption came from Eta Carinae, a star about 7,500 light-years away from Earth that is one of the most massive stars in our Milky Way galaxy. It blazed into ultra-brightness in 1838, becoming the second-brightest star in the sky for 10 years in a rare celestial outburst later dubbed the "Great Eruption." The star later dimmed, and is now not even in the top 100 list of brightest stars.

"Eta Carinae is probably the most studied object in our galaxy," said Armin Rest, an astrophysicist at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore and the study's lead author.

Scientists have found that Eta Carinae is a kind of star known as a luminous blue variable, meaning it goes through episodes of dimness and brightness. These rises and falls in luminosity are caused by mounting instability within the star followed by a dramatic loss of mass. The Great Eruption of Eta Carinae was an especially catastrophic event, where the star — once about 140 times the mass of the sun — lost mass equal to about 20 times that of the sun.

Scientists believed this rare kind of eruption was caused by a stellar wind blowing off the stars. Still, much remained uncertain, since a key detail about the Great Eruption was missing — its pattern of light. This spectrum would help yield details such as the temperature, composition and velocity of matter from the eruption. [Amazing Photos of Star Explosions]

For instance, "cool objects emit redder light than hot objects," Rest explained. "Look at an ember — if it is relatively cool, it is dark red, and the hotter it gets, the bluer, whiter it gets. So overall the color of the spectra gives you already a good idea how hot or cold the star is."

Now, using the Magellan and du Pont telescopes at Las Campanas Observatories in Chile, Rest and his colleagues have discovered spectra from the Great Eruption, by looking for light from the explosion that bounced or echoed off interstellar dust tens of light-years from the star.

"The missing piece, the big gap, has been that there were no spectra of the Great Eruption," Rest said. "Now we have it, and it gives us the chance to better understand how this eruption happened and what caused it."

Surprisingly, their observations suggest the Great Eruption is different from so-called "supernova impostors," events that resemble the explosive supernova deaths of stars but are thought to be eruptions from bright blue variables. For example, the Great Eruption was only about 8,540 degrees Fahrenheit (4,725 degrees Celsius), much cooler than allowed by the stellar winds used to explain supernova impostors.

"This star's Giant Eruption has been considered a prototype for all supernova imposters in external galaxies," said study co-author Jose Prieto, now at Princeton University. "But this research indicates that it is actually a rather unique event."

These new findings mean that researchers still do not know what caused the Great Eruption.

"With Eta Carinae, we are dealing with a really extreme phenomenon, which drags us into unexplored territory as far as theory is concerned," Rest said. "We do have some ideas — a collision between two stars in a binary system; an explosive but non-terminal thermonuclear burning event in the core of the star that might release energy — but these are really just ideas and have not been very well-developed, so we don't yet have clear predictions for the observed phenomena we expect to see."

The scientists now plan to look for more light echoes from the Great Eruption, to see how Eta Carinae altered over time, "and that will further help in constraining what the eruption mechanism is," Rest said.

The scientists detailed their findings in the Feb. 16 issue of the journal Nature.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcomand on Facebook.