Are scientists close to uncovering the Higgs boson?

Researchers analyzing data from Fermilab's now-defunct Tevatron particle accelerator say that they may have glimpsed evidence of the elusive Higgs boson, the so-called God particle thought to be responsible for giving all other particles mass.

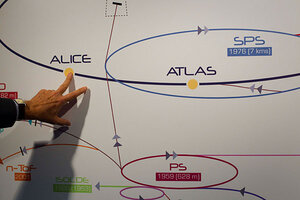

In this photo taken in May 2011, a physicist at the at the European Center for Nuclear Research explains an illustration showing what a Higgs boson may look like. Scientists at U.S. Fermilab reported that they have spotted likely signs of the elusive particle.

Anja Niedringhaus/AP/File

New evidence makes it more likely than ever that 2012 will be the year physicists finally find the long-sought Higgs boson particle.

The particle has been predicted as the explanation for why all other particles have mass. It has earned the nickname the "God Particle," largely from the popular media, though scientists haven't warmed to the name.

Yet despite years of searching, scientists have yet to detect the Higgs boson directly.

Now physicists at the Tevatron particle accelerator at Illinois' Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory report hints in their data that suggest the particle may exist with a mass between 115 to 135 giga-electron volts, or GeV (for comparison, a proton has a mass of about 0.938 GeV).

"We see a distinct Higgs-like signature that cannot be easily explained without the presence of something new," physicist Wade Fisher of Michigan State University said in a statement. "If what we're seeing really is the Higgs boson, it will be a major milestone for the world physics community and will place the keystone in the most successful particle physics theory in history."

That theory, called the Standard Model, has been successful in describing all the known fundamental particles in the universe. The Higgs boson is the only remaining particle that has been predicted by the theory, but never seen. [5 Implications of Finding the Higgs Boson]

The Tevatron findings agree with independent signs announced in December 2011 by scientists at the world's largest atom smasher, the Large Hadron Collider in Geneva, Switzerland. There, too, researchers saw hints of an excess of particle events corresponding to something with a mass in about that range.

However, in neither case could the researchers confirm for sure that what they see is a new particle and not simply signals created by background events. More data must be gathered before the signals can be considered statistically significant enough to qualify as a discovery.

"The end game is approaching in the hunt for the Higgs boson," said Jim Siegrist, the associate director of Science for High Energy Physics at the U.S Department of Energy, which funds the Tevatron experiments. "This is an important milestone for the Tevatron experiments, and demonstrates the continuing importance of independent measurements in the quest to understand the building blocks of nature."

Both Tevatron and the LHC search for the Higgs by accelerating particles to near the speed of light inside giant underground rings. When two speeding particles collide head-on, they produce energetic explosions that can give rise to exotic particles, some of which may never have been seen before.

The new results, which come from two experiments at Tevatron called CDF and DZero, were announced today (March 7) at the Rencontres de Moriond conference in Italy.

"I am thrilled with the pace of progress in the hunt for the Higgs boson," said Fermilab director Pier Oddone."CDF and DZero scientists from around the world have pulled out all the stops to reach this very nice and important contribution to the Higgs boson search. The two collaborations independently combed through hundreds of trillions of proton-antiproton collisions recorded by their experiments to arrive at this exciting result."

Tevatron's findings are in a way a cry from the grave. The accelerator is no longer running — it was shut down for good last fall after an 18-year career. The new results were gleaned from data gathered over the last few years before the facility was retired.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.