Dressed to kill: A feathered tyrannosaur is discovered in China

A team of paleontologists has dubbed their find Yutyrannus huali – beautiful feathered tyrant. At 1.5 tons, this 'fuzz ball ... with a mouth full of killer teeth' is the largest feathered dinosaur by far.

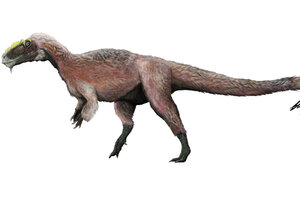

This artist concept provided by the Beijing Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology shows a new species of tyrannosaur, Y. huali, discovered in China.

Brian Choo/Beijing Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology/AP

It's not often you see a dinosaur with a girth and toothy grimace reminiscent of Tyrannosaurus rex yet covered in a downy winter coat worthy of L.L. Bean.

But that's what a team of paleontologists in China reports. They've dubbed their find Yutyrannus huali (beautiful feathered tyrant), a creature that stretched 30 feet from tail-tip to snout and weighed 1.5 tons.

It's the largest dinosaur yet to host feather-like features all over its body – features well preserved on three nearly complete, mostly intact fossil skeletons the team found.

“It's very intriguing to think of this very large fuzz ball running around with a mouth full of killer teeth,” quips Hans-Dieter Sues, curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Smithsonian Institution's Museum of Natural History in Washington.

But, he adds, the discovery addresses a serious question researchers have asked since the first fossils of feathered dinosaurs were uncovered in the 1990s: How widely do they appear among the various types of dinosaurs?

Meat-eating dinosaurs hosting feathers makes sense, Dr. Sues says, because they are the ancestors of modern birds. But if the covering extends to the vegetarians as well, it would imply that feathers of some sort came from a common primitive dinosaur ancestor to both the carnivores and vegetarians, Sues suggests. That in turn raises the question: Would feathers have helped the earliest dinosaurs gain an evolutionary advantage over their rivals, many of which had dinosaur-like features in their skeletons, but became dead-end branches on the so-called Tree of Life. Meanwhile, the dinosaurs survived, ruling the planet for nearly 200 million years.

Until now, the most heavily feathered fossils tended to be smaller creatures – Yutyrannus huali might have considered many of them tasty hors d'oeuvres. They were small enough to need some form of insulation to help them retain body heat, Sues explains.

Using modern large animals such as elephants as models, however, many researchers suspected that larger animals would have evolved to shed feathers as they grew in size in order to get rid of body heat from their own exertion as they lumbered along in a tropical or semi-tropical climate.

Yet in Y. huali, researchers have uncovered a dinosaur of substantial stature fully feathered. It weighs some 40 times as much as the previous feathered record-holder.

“It's an extraordinary find,” says Sues, who was not a member of the team making the discovery.

The fossils date to the early Cretaceous period, which spanned roughly 46 million years, beginning about 145 million years ago. They come from a quarry in Liaoning Province, which shares a border with North Korea.

According to the researchers, two museums in China originally acquired the fossils from a dealer, who was unsure which quarry in the province the specimens came from. But as paleontologists from the Chinese Academy of Sciences' Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology prepared the specimens for long-term preservation and study, the fossils' state of preservation and the rock type in which they were embedded helped them locate the likely quarry and rock formations that yielded the specimens.

The feathers on Y. huali “were simple filaments,” notes Xu Xing, a researcher from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology who oversaw the fossils' preparation and is the lead author of a paper formally presenting the find in today's issue of the journal Nature.

“They were more like the fuzzy down of a modern baby chick than the stiff plumes of an adult bird,” he said in a prepared statement.

The climate on Earth during much of the Cretaceous was akin to today's climate in Florida or southern Louisiana. But in the early part of the Cretaceous, when Y. huali scared the stuffing out of lesser creatures, the climate was cooler. This led the team to suggest that perhaps Y. huali did need insulation to retain sufficient body heat, despite its giant size.

Indeed, some researchers have wondered if even the fearsome T. rex, which lived during the latter, warmer part of the Cretaceous, might have had its own coat of many feathers. No evidence for that has emerged, although some speculate that T. rex “chicks” might have started life with a down coat. Now that Y. huali has appeared, the thought of a fuzzy T. rex may have become a bit less far-fetched, some researchers say.

Whatever the outcome of that discussion, Sues notes that fossils have revealed a sartorial splendor in dinosaurs that casts “Jurassic Park's” scaly-skinned, voracious raptors a new light.

In reality, “they are basically chickens from hell,” Sues says with a chuckle.