SpaceX's Dragon craft is a star performer, so far

The Dragon spacecraft passed the underside of the space station and correctly calculated the distance between the two – two tests it cleared with flying colors on Thursday. The craft, owned by SpaceX, is set to dock on Friday.

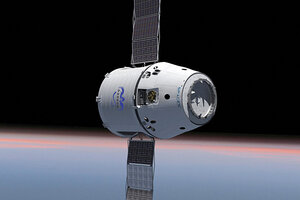

This computer generated image provided by SpaceX shows their Dragon spacecraft with solar panels deployed.

SpaceX/AP

With the relentless flash of a strobe light and some on-board number crunching, SpaceX's Dragon spacecraft cleared two more significant milestones Thursday in the company's effort to become the first commercial launch service to carry cargo to the International Space Station.

Appearing like a gnat silhouetted against the brilliance of Earth's cloud tops, Dragon passed within 1.5 miles of the station's underside in a test of its ability to receive data from the space station on the station's position – determined by Global Positioning System satellites – and accurately determine the distance and relative positions between the two craft.

In addition, space-station flight engineer André Kuipers activated a strobe light on Dragon, showing that the station crewmembers could command the cargo craft from their enviable perch in the multiwindowed cupola on the station – in essence the station's control tower for overseeing the arrival and departure of spacecraft from station partners.

SpaceX already is under a $1.6 billion contract with NASA for 12 cargo missions through 2015. But the company has its sights set on more than rations and experiment samples. A successful cargo service also paves the way for sending humans into space.

The company currently is one of four firms in which NASA is investing almost $270 million to develop human-spaceflight capabilities in the second phase of its commercial-crew development project. NASA is relying on commercial providers to ferry crews and cargo to and from the space station so that the agency can focus its human-spaceflight efforts on exploring space beyond low-Earth orbit, the space station's domain.

SpaceX's entry into that competition is a human-rated version of the Falcon 9 rocket, which lofted Dragon, and the Dragon craft. SpaceX designed Dragon from the outset to ferry people as well as petri dishes.

Thursday's activities would have wrapped up this mission in a sequence of three demonstration flights NASA originally envisioned for SpaceX. Efforts to dock with the station would have been the third mission. But the company was able to show that the two missions could be combined.

The intense preparations appear to have paid off so far. NASA and SpaceX have worked together on this mission for five years and began joint simulations nearly three years ago, notes John Couluris, SpaceX's mission director for this flight. The pace picked up during the past 18 months, with NASA and SpaceX conducting nearly 20 joint simulations and the company conducting more than 40 internally.

SpaceX has exclusive control of its craft after launch. But when Dragon reaches the space station's vicinity, controllers at NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston, as well as station crew members, have authority to halt docking attempts. The space station's lead flight director, Holly Ridings, noted that the activities Thursday were as much a test for how well the agency, the space-station crew, and the company could work together during a mission as they were for hardware performance.

“This was the first joint operation,” she noted, pronouncing it “very successful.”

“So far, our mission has been proceeding just like our regular simulations, so we're very pleased with that,” Mr. Couluris added during a press briefing Thursday morning.

Indeed, some hardware is working better than expected. For instance, the SpaceX team initially estimated that Dragon would have to close to within 14 to 17 miles of the station before it could establish a reliable communications link between the two craft. It's the link that station crew members use to send commands to Dragon and the link that Dragon uses to receive data the station sends on its position. The two craft established a communications link while Dragon was more than 56 miles away.

“That was a great thing for us,” Couluris said. The longer-lasting communications link may allow the company to streamline some of its predocking procedures, he added.

At the time of this writing, engineers in Houston and Hawthorne, Calif., were reviewing the GPS data to ensure that Dragon's navigation system succeeded in tracking the two crafts' positions in relation to each other.

Another bonus: Dragon has more fuel left on board than planners anticipated for this point in the mission – important if the rendezvous effort on Friday should require more than one attempt.

Dragon will spend the rest of Thursday performing an enormous loop-the-loop around the space station to reposition itself for a final approach, rendezvous, and docking on Friday. The docking process has several holding points along the way, as Dragon closes in on the station. At each, NASA and SpaceX will determine if conditions on Dragon and the space station allow Dragon to move to the next holding point.

If all goes well, Dragon's final maneuver will bring it to within about 33 feet of its docking port. Ms. Ridings says she anticipates a go, no-go decision for docking at about 8 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time Friday. Assuming the decision is “go,” station flight engineer Don Petitt will used the station's robotic arm to grasp Dragon and gently dock it.

While Thursday's successes on this test flight for SpaceX have given the comanyu's mission controllers additional confidence in their craft, they are keenly aware that docking is no slam-dunk. “It will be a more intensive day tomorrow,” Couluris observes.