NASA's Curiosity rover to explore bizarre Martian mountain

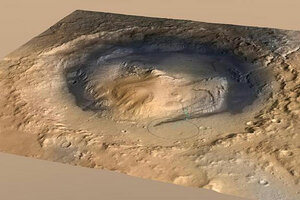

The three-mile-tall Mount Sharp is an inviting target for investigation by NASA's one-ton Mars rover, which is scheduled to touch down on the Red Planet on Aug. 5.

NASA's 1-ton Curiosity rover will land in August 2012 near the foot of Mount Sharp inside Mars' Gale Crater.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/ESA/DLR/FU Berlin/MSSS

The towering mountain that NASA's next Mars rover will explore after landing on the Red Planet next month remains mysterious to scientists, who say there's nothing quite like it here on Earth.

Mount Sharp rises 3 miles (5 kilometers) from the center of Mars' huge Gale Crater, where the car-size Curiosity rover will touch down on the night of Aug. 5. Curiosity scientists are eager to study the mountain, whose many layers preserve a record of the Red Planet's changing environmental conditions going back perhaps a billion years or more.

Curiosity's rovings could also help the team understand how Mount Sharp formed, because they're not entirely sure.

"In one go, you have flat-lying strata that are 5 kilometers thick. There's nothing like that on Earth," said Curiosity lead scientist John Grotzinger, of Caltech in Pasadena. "We don't really know what's going on there." [Curiosity - The SUV of Mars Rovers]

Exploring Mount Sharp

The 1-ton Curiosity rover is the centerpiece of NASA's $2.5 billion Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) mission, which launched in late November. MSL's main goal is to determine if the Gale Crater area is, or ever was, capable of supporting microbial life.

To get at this question, Curiosity will investigate the different layers of Mount Sharp, which is taller than any peak in the continental United States.

Life as we know it depends on liquid water. So the rover will probably spend a lot of time poking around Mount Sharp's lower reaches, where Mars-orbiting spacecraft have spotted signs of minerals that form in the presence of water, such as clays and sulfates.

But there are reasons to climb higher. If Curiosity gets about 2,300 feet (700 meters) up the mountain, for example, it will cross a boundary, encountering layers that don't show signs of hydrated minerals. Higher still are strata that appear to have been deposited by the wind in a rhythmic pattern, perhaps indicating climate cycles, Grotzinger said.

Studying these higher layers could help scientists better understand why Mars shifted from a relatively wet world billions of years ago to the dry and desolate planet we know today — a transition marked by what Grotzinger dubbed the "Great Desiccation Event."

"The question is, what was that event? What was that trigger? What happened environmentally?" Grotzinger told SPACE.com. "My hope is that we'll get some insight into this Great Desiccation Event."

Mount Sharp is comparable in shape to the huge volcanoes of Hawaii, with gentle slopes that Curiosity can tackle. The rover might be able to climb all the way to the top, given enough time, researchers have said. But summitting the peak is not high on the MSL team's priority list at the moment.

Building a mountain

Curiosity's rovings could help solve another mystery: exactly how Mount Sharp formed. While Grotzinger and other scientists have some ideas, the jury is still out.

What does seem clear is that the 96-mile-wide (154-km) Gale Crater, which formed after an asteroid impact long ago, was once entirely filled in. Mount Sharp is thus the remnant of a much larger mound, the bit that has yet to be whittled away by erosion.

Researchers are also confident that Mount Sharp's base had extensive contact with water. But they're not sure if these lower layers indicate that a lake once filled Gale Crater, or if Mars' water table rose and soaked material that had been deposited by the wind.

The wind likely did play a major role in building Mount Sharp, said Ken Edgett, of Malin Space Science Systems in San Diego, principal investigator for Curiosity's Mars Hand Lens Imager instrument, or MAHLI.

"I don't see how you do it without most of that stuff falling out of the sky," Edgett told SPACE.com in April.

Curiosity's efforts should help scientists sort out the details, he added.

"We should be able to get a handle on, 'What is this stuff?'" Edgett said.

Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also onFacebook and Google+.

- Mars Rover Curiosity: Mars Science Lab Coverage

- Occupy Mars: History of Robotic Red Planet Missions (Infographic)

- 7 Biggest Mysteries of Mars

Copyright 2012 SPACE.com, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.