'Seven minutes of terror': Mars rover landing will be a nail-biter

Scientists are utilizing a complicated new 'sky crane' technique for landing the car-sized Curiosity rover on Mars Monday. The hope is that the good luck NASA has had with Mars missions will hold up.

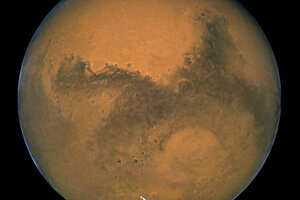

NASA's Hubble Space Telescope snapped this shot of Mars on Aug. 26, 2003, when the Red Planet was 34.7 million miles from Earth. The picture was taken just 11 hours before Mars made its closest approach to us in 60,000 years.

NASA/ESA

NASA calls it "seven minutes of terror" – the final minutes that the one-ton Mars rover Curiosity must survive to cap an eight-month interplanetary cruise.

Using a unique "sky crane" approach, a rocket-powered descent module will gently ease a tethered Curiosity onto the red planet's surface, then release the rover and fly off to crash at a safe distance from the landing site.

It's a method that will present more than its share of nail-biting moments. Indeed, at press briefings and in messages to their staffs, NASA managers have tried to underscore just how risky this venture is.

While using any new technology for the first time on such a high-profile space mission carries risks of failure, if history is any guide, the odds for success may be somewhat higher than NASA publicly acknowledges.

Slated to arrive on the surface of Mars at 1:31 a.m. Eastern Daylight Time Monday, the rover is the most expensive, scientifically ambitious robotic craft humans have ever tried to place on another planet.

The goal of the $2.5-billion mission is to determine if Gale Crater and its central summit, informally known as Mt. Sharp, once presented an environment that at least simple forms of life could have called home.

Humanity's track record for Mars missions isn't stellar, James Green, NASA director of planetary science, suggested in an email posted July 29 on the website planetarynews.com.

Since 1960, when the first attempt at a Mars flyby was made by the Soviet Union, "the historical success rate at Mars is only 40 percent," he wrote.

That figure, however, includes all space-faring nations, such as Russia, pre- and post-Soviet collapse, which is 0 for 19, most recently with the loss of last year's Phobos-Grunt mission to study the moons of Mars. Out of the 18 mission NASA lists with Mars as the destination or as the main target for a flyby, the agency has a batting average of .730. Of the attempts at landing spacecraft on the surface, beginning with the Viking missions in 1975, the agency is six for seven.

"Getting onto the surface of Mars safely is hard," says Mark Lemmon, a planetary scientist at Texas A&M University in College Station.

How hard? Ask him about Mars Polar Lander, which was lost on landing in December 1999. He was on the science team for the lander, one of several recent Mars missions on his resume.

"I was slightly emotionally scarred by that experience," he says.

With Curiosity "I think our chances are good," he adds. "I've seen people who thought this was a scary approach to Mars exploration look at it in detail and come away and say: This is actually a really good idea."

This is not the first time engineers have reached outside the box for a Mars mission. Sixteen years ago NASA dropped its first rover onto Mars using an unorthodox method – encasing it in a cocoon of inflatable air bags.

Parts of the delivery system looked much like Curiosity's. At a predetermined altitude above Mars, a rocket-equipped descent module lowered Sojourner Truth and its landing platform via cables far enough to allow the rover's protective air bags to inflate. The module cut the cables, and the rover in its cocoon dropped to the surface, bouncing along the surface with ever smaller hops until it came to rest.

The bags then deflated, leaving the rover to drive down a ramp and explore its new home. When telemetry indicated that the airbags had deflated and that the rover and its landing platform were upright and healthy, cheers and high-fives erupted in mission control.

"Going into Pathfinder, there were a lot of people who said: ‘That is a strange, new system; why would you ever consider using such a thing?’" Dr. Lemmon says. “Now, everyone points to that as a way to go.”

The twin rovers Spirit and Opportunity, which arrived at Mars separately in January 2004, also used the airbag approach. Spirit fell silent in March 2010. Opportunity is still exploring its patch of the planet, logging 21.52 miles since its arrival.

The sky crane "looks a bit crazy," acknowledges Adam Steltzner, the rover's lead engineer at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. "I promise you it's the least crazy of the methods you could use to land a rover the size of Curiosity on Mars.... I'm fairly confident that [the landing] will be a good night for us."

During the "seven minutes of terror," the descent vehicle is expected to slam into the Martian atmosphere at 13,000 miles an hour. Kept on course by small steering jets, the vehicle will release its single parachute after slowing to about 1,000 miles an hour. About a mile above the surface, the descent module then will release the chute, drop its heat shield, and the module's eight rocket motors will ignite, braking further to about 200 miles an hour.

The ultimate goal is to slow the descent to about 1.5 miles an hour, while descending straight down. About 70 feet above the surface, the module will begin lowering Curiosity until it dangles about 24 feet below the module. When the descending module senses that the rover is squarely on the surface, it will cut the cables and fly off to crash a safe distance away.

The fully automated landing system is designed to sense its track during descent and steer itself, an approach that's never been used before. This leads to a more precise landing, shrinking the size of the projected landing zone from 62 miles for past missions to 12 miles. That tighter landing zone makes a successful touchdown in Gale Crater possible.

Of the seven minutes, three are the most tension-filled, Steltzner noted during a briefing Thursday. The guided descent and the use of the sky crane are obvious nail-biters. The other involves a huge 70-foot-wide parachute, which must endure supersonic descent speeds.

Parachutes are "fundamentally sketchy kinds of devices," he says. Unlike, say, paratroopers, Curiosity has no back-up parachute due to design considerations.

While history is replete with failed Mars missions, with Curiosity, Lemmon says "you've got to look at the experience of the people doing it and say: You've got some reasonable confidence. If anyone can do it, the team that's running Curiosity can.”

How confident is he? "I have a lease on an apartment here in Pasadena for the next three months," he says. But, he adds, "there's an escape clause."