Scientists surprised to find pair of black holes keeping each other company

Black holes are the densest objects in the universe, with the largest ones, found at the centers of galaxies, containing millions to billions times more mass than the sun.

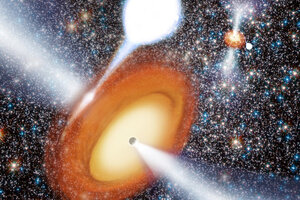

An artist's conception of a black hole in globular cluster.

Benjamin de Bivort; Strader, et al.; NRAO/AUI/NSF

Black holes might seem too monstrous to keep company, but surprising new findings suggest they can live in groups within clusters of stars inside our Milky Way galaxy, researchers say.

The presence of multiple black holes within these clusters might drastically alter the way way these major components of galaxies evolve, scientists added.

"Before this work, there were zero black holes known in Milky Way globular clusters, so even finding one would have been exciting," said lead study author Jay Strader, an astronomer at Michigan State University in East Lansing.

Black holes are the densest objects in the universe, with the largest ones, found at the centers of galaxies, containing millions to billions times more mass than the sun. Stellar-mass size black holes are born from the explosive deaths of stars known as supernovas.

Hundreds of black holes, each with the mass of a star, probably form in globular clusters, spherical collections of hundreds of thousands of stars that orbit the center of the galaxy. However, past research suggested these clusters would never house multiple black holes at any one time. Since black holes are so massive, they tend to fall toward the center of globular clusters, similar to how denser materials made their way to Earth's center during its formation. At the hearts of clusters, these black holes would gravitationally tug at each other and tend to kick all, or perhaps all but one, out of the clusters.

Based on radio emissions, however, scientists have apparently discovered a pair of black holes within the large globular cluster M22, located about 10,600 light-years away in the constellation Sagittarius, near the Milky Way's bulge. M22 is one of the brightest globular clusters in the night sky, and holds nearly a million stars. [The Strangest Black Holes in the Universe]

Surprising find

"Contrary to our previous thoughts, globular clusters might be one of the best places to look for black holes, rather than one of the worst," Strader told SPACE.com.

And M22 might harbor even more black holes, if they exist without the glowing accretion disks astronomers are accustomed to detecting, Strader added. "We estimate that a population of five to 100 black holes may exist in the cluster," he said.

The researchers detected the two black holes, named M22-VLA1 and M22-VLA2, based on radio emissions captured by the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array of radio telescopes in New Mexico. These black holes are both binary systems, each possessing a companion star they are ripping matter from. This stolen gas and dust collects around each black hole in a glowing accretion disk, much like water swirling down a drain. The emissions from these disks are what astronomers see — otherwise, black holes are, well, black, and largely hidden against the night sky. The brightness of these disks suggests their black holes are 10 to 20 times more massive than the sun.

"One of the most interesting aspects of this work is that we found the black holes via radio emission," Strader said. "All the other stellar-mass black holes in our galaxy have been discovered by X-ray emission rather than radio. We hypothesize that the reason our sources haven't been seen in previous X-ray searches is that they aren't accreting very much matter at all, so they don't produce the hot accretion disks that glow in the optical and X-rays.

"If this is true, it suggests that radio observations could be a good way to find the quieter accreting stellar-mass black holes in our galaxy."

The researchers had looked into M22 in hope of finding evidence for a rare type of black hole in the cluster's center — what scientists call an intermediate-mass black hole, with hundreds of thousands of times the sun's mass.

"We didn't find what we were looking for, but instead found something very surprising — two smaller black holes," study author Laura Chomiuk at Michigan State University and the National Radio Astronomy Observatory said in a statement.

The findings suggest the process of black hole ejection from globular clusters is less efficient than has been thought, especially when there are relatively few black holes to gravitationally sling their brethren outward. For instance, by energizing the areas around them, black holes may reduce the density of their environment and thus the rate at which they hurl each other out of the cluster.

"Future computer simulations of the evolution of globular clusters with populations of black holes should help address this issue," Strader said.

He added, "My personal view is that it's likely that other clusters also have black holes that we just haven't found yet."

Facing the consequences

The consequences of multiple black holes in a globular cluster might be dramatic. Black holes can essentially heat their environments by interacting with nearby stars and transferring energy to them. The coexistence of multiple black holes relatively near each other may mean globular clusters get hotter than thought, reducing their density and basically slowing down their evolution – keeping matter from condensing into stars and planets, Strader said.

M22-VLA1 and M22-VLA2 may continue to peacefully coexist. On the other hand, perhaps one will gravitationally pull at and eventually sling the other and its companion star out of the cluster. Or perhaps the black holes will violently merge to form an even larger black hole.

"Any of these fates are possible, and will depend on other details, such as whether the cluster has other black holes that we haven't observed yet," Strader said. "Probably the most likely outcome is that at least one of the black hole binaries is ejected from the cluster at some point in the future, but it's possible that both could survive for several billion more years."

When it comes to how many black holes might coexist in globular clusters, Strader said a large number is unlikely. "The question is one of time scales," he said. "Even in M22, if you waited for several billion more years, it's possible that all but one or all of the black holes will have been ejected."

The scientists feel they have strong evidence these radio signals come from black holes in M22, "but it's not airtight," Strader said. "There is a small chance that these objects could instead be very distant background galaxies that just happened to be aligned with the center of this globular cluster."

"We can test whether this could be true by measuring the motion of the sources on the sky," Strader added. "If they are in the cluster, they should move pretty quickly, and in a way that has already been mapped out for stars in the cluster. If they are in the background, they won't appear to move on the sky at all. So we've applied for additional telescope time to test this idea, and if we get the time we'll know in about a year whether they are moving as expected."

The researchers now also plan to search for radio signals from similar black holes in other Milky Way globular clusters over the next few years. "A search like this will tell us whether black holes in globular clusters are rare or common," Strader said.

The scientists detailed their findings in the Oct. 4 issue of the journal Nature.

You can follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.