Earth is less of a backwater than we thought, say astronomers

The galactic spiral arm where our solar system resides may be a big deal after all, according to a new analysis.

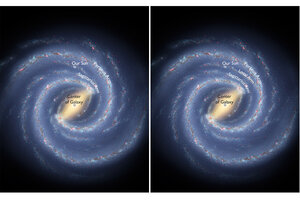

At left, the 'old' model of the Milky Way and our place in it. At right, the 'new' model, in which our solar system's Local Arm is a more prominent branch of the Perseus Arm.

Robert Hurt, IPAC; Bill Saxton, NRAO/AUI/NSF

Astronomers seem to delight in reminding us of our unimportance. Our planet, they're constantly telling us, is a backwater, a tiny speck circling an ordinary star on the boring periphery of a middling galaxy.

The astronomer Carl Sagan was the undisputed master of taking us down billions and billions of notches. Here he is in his 1980 book, Cosmos, doing his very best to make us feel completely insignificant:

"For as long as there been humans we have searched for our place in the cosmos. Where are we? Who are we? We find that we live on an insignificant planet of a humdrum star lost in a galaxy tucked away in some forgotten corner of a universe in which there are far more galaxies than people."

For those of you whose self-esteem is linked to your proximity to the center of the universe, this is depressing stuff. We're living, it seems, in the cosmic equivalent of flyover country.

Or maybe not. New research shows that our planet might not be quite the provincial, iceberg-lettuce-eating exurbia that astronomers once thought. A new suggests that our galactic neighborhood is actually a pretty vibrant place.

We reside on a spiral arm of the Milky Way known as the Local Arm, which sits between two big spiral arms called the Sagittarius Arm and the Perseus Arm. Previously, astronomers regarded our Local Arm as a minor spur, a barely noticeable nubbin of stars dangling between its two majestic neighbors. But now it seems that the Local Arm is a big deal in its own right.

"Our new evidence suggests that the Local Arm should appear as a prominent feature of the Milky Way," said Alberto Sanna, of the Max-Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy, in a press release. Sanna and his colleagues presented their findings to the American Astronomical Society's meeting in Indianapolis this week, and details of their findings are published in the Astrophysical Journal.

Mapping the Milky Way is notoriously difficult because all of our telescopes are inside it. Astronomers still disagree about the number of spiral arms and their exact location.

To help determine the size and structure of our Local Arm, researchers used data from the National Science Foundation's Very Long Baseline Array, a set of ten huge radio antenna dishes, distributed from Hawaii to the Caribbean, that together are capable of making our most precise measurements of the positions of celestial objects.

Astronomers calculate distances to stars and other bodies by taking advantage of parallax, the apparent shift in position of an object viewed from two different lines of sight. (Think of how objects close to your face will jump back and forth when you alternately wink each eye.) They start by noting the positions of stars in June and then again in December, when our planet is on opposite sides of the sun. With some simple trigonometry, the researchers were able to find many stars and star-forming-regions in our Local Arm.

"Based on both the distances and the space motions we measured, our Local Arm is not a spur. It is a major structure, maybe a branch of the Perseus Arm, or possibly an independent arm segment," said Sanna.

Still, we shouldn't get ahead of ourselves. Our solar system is still about 30,000 light years from the center of the galaxy – hardly commuting distance. And our galaxy is just one of at least 100 billion galaxies. So, while this new analysis puts us in a more popular galactic ZIP code, it's not as though we're suddenly at the center of the universe.

Of course, the universe probably has no center, because in order to have a center you have to have an edge, and astronomers believe that our universe is spatially unbounded, strange as that may sound.

But if being at the center of things is important to you, remember that you're always at the center of the observable universe. All you need to do is look up.