Ancient, cow-sized knobby lizard discovered in Africa

The eccentric animal presided over a lonely desert some 260 million years ago, when Earth was home to a single continent, Pangaea.

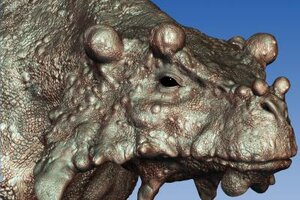

Artist's rendering of the pareiasaur Bunostegos, a cow-sized, plant-eating reptile that roamed the ancient central desert of Pangea over 250 million years ago.

Credit: Illustration by Marc Boulay.

Marc Boulay/Society of Vertebrate Paleontology

Even by paleontology standards, this newly discovered lizard was unusual-looking, an outcast in the ancient Earth’s nearly empty deserts.

The cow-sized animal, called Bunostegos, or "knobby roof” for the quantity of huge bulbs that dot its face, looking like bubbling cooking oil, presided over a lonely desert some 260 million years ago, when Earth was home to a single continent, Pangaea.

Found in modern Niger’s north desert, the lizard belongs to the genus pareiasaur, herbivore animals that lumbered around the Earth in its Permian period. Most pareiasaurs had knobs protruding from their skulls, but Bunostegos’s bulbous ones are unusual even for that class of animals, as the largest ever seen.

"Imagine a cow-sized, plant-eating reptile with a knobby skull and bony armor down its back," said lead author Linda Tsuji, of the University of Washington, in a statement.

Scientists have found that the knobbed lizard was more related to primitive lizards from which it had split off millions of years earlier than it was to its contemporaries. That supports the scientists’ hypothesis that central Pangaea was home to a desert whose sheer inaccessibility kept its ecosystem bounded off from the rest of the continent. Few animals ventured into the place, and those that did call it home seldom left it. That meant life there, including the knobbed lizard, lived in evolutionary solitude, growing more and more unlike their cousins in Pangaea’s more hospitable corridors.

“The endemic tetrapod fauna of Niger supports the theory that central Pangea was biogeographically isolated from the rest of the supercontinent by desert-like conditions during Late Permian times,” the scientists wrote in the paper, published in The Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

The knobs on the droopy-faced lizard’s head were likely scaly-skin covered bones, similar to those found on the heads of modern giraffes, but scientists are not sure what function the protrusions served. Rather than act as weapons, the horns could have helped the animals tell each other apart, avoiding awkward occasions of mistaken reptilian identity out there in the desert, scientists told BBC News.

The curious-looking animal was wiped out along with most of its contemporaries about 248 million years ago, when an unknown event, possibly an asteroid plunging into Earth, obliterated the ancient animal kingdom.

The scientists said that the lizard find could help in putting together a better portrait of the world that came before us.

"Research in these lesser-known basins is critically important for meaningful interpretation of the Permian fossil record,” said Paleontologist Gabe Bever, in a statement. “Our understanding of the Permian and the mass extinction that ended it depends on discovery of more fossils like the beautifully bizarre Bunostegos."