Ancient predator lacked jaw strength to leverage own fangs, was 'embarrassing'

The extinct and highly unusual predator Thylacosmilus atrox relied on brute brawn to pin its prey.

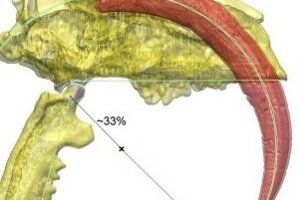

The huge canine teeth of Thylacosmilus atrox extended almost into its braincase.

The University of New South Wales

“Grandmother, what big teeth you have!” exclaimed Little Red Riding Hood.

“All the better to eat you up with,” replied the wolf, which had just gobbled up the girl’s relative and strategically donned some of her accessories.

Well, not necessarily. It turns out that big teeth don't always mean a big bite, especially if the animal lacks the strong jaws to wield them.

The hulking, toothy predators that roamed the earth millions of years ago have long been figures of lore for sinking their horrible teeth into the animals unlucky enough to keep company with them. One of the animals in the sabre-tooth lineage, a South American version called Thylacosmilus atrox, had two massive teeth, each with roots stretching back to its braincase and that protruded from its mouth like angry warnings to run away, fast. The catch is, this extinct animal, a species whose closest living relatives are the Australian and American marsupials, had a bite no more powerful than that of a modern domestic cat.

Scientists have found that the worryingly toothy animal actually lacked the sheer jaw power to leverage its own teeth. Instead, the ancient mammal had to rely on its brawn to snag its food, pinning its prey with its muscled arms before administering a precise, strategic bite that depended entirely on its neck muscle force.

“Thylacosmilus looked and behaved like nothing alive today,” said University of New South Wales palaeontologist Stephen Wroe, the leader of the research team. “Frankly, the jaw muscles of Thylacosmilus were embarrassing."

To make those findings, published in PLOS ONE, scientists built three-dimensional computer models that played out how three feared animals chased and killed their prey: Thylacosmilus, its cousin, the classic North American sabre-toothed ‘tiger’ (Smilodon fatalis), and the modern leopard.

The models showed that that both of the extinct species had extremely weak jaws relative to the modern leopard, with those of the odd Thylacosmilus being the weakest. That means that Smilodon fatalis, a true member of the cat family, was similarly dependent on sheer brawn, rather than wickedly punishing jaws, to kill its food.

Lest it be too much of an embarrassment to legend, where Thylacosmilus did have an advantage was in its skull, which was uniquely adapted to absorb the stress of plunging its fangs into hapless animals.

“Grandmother, what a big neck and well-adapted skull you have,” said Thylacosmilus’s prey, allegedly.