Exoplanet's deep blue color a surprise to scientists

For the first time, scientists have determined the color of a planet outside our solar system.

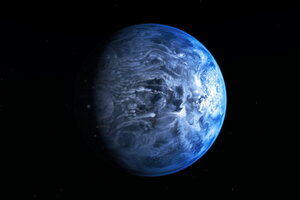

An artist's impression shows one of Earth's nearest planets outside the solar system, named HD 189733B. Scientists recently determined that the planet is a deep blue color.

M. Kornmesser/ESA-Hubble/AP

Astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope have for the first time determined the true color of a planet outside our solar system. The planet, known as HD 189733b, has seemingly earned the HD in its functional title, having proved to be a high-definition-like azure blue.

That deep blue color came as surprise, since scientists had expected the planet to be either dark or white. One prediction was that HD 189733b was swaddled in sodium gases that would absorb most of the visible light, leaving it dark. Another was that the atmosphere was instead laced with silicates that would reflect the light, making it white.

“The blue color was totally unexpected,” said Frédéric Pont, senior lecturer in astrophysics at The University of Exeter.

Dr. Pont proposes that the blue color could be the result of "glass rain." Silicate particles in the planet's atmosphere could scatter the bluish wavelengths coming from its star, just as tiny particles in Earth's atmosphere do with light from our sun, which our oceans then reflect back into space.

This is all conjecture, however. “I wouldn’t bet my house on the silicate explanation,” said Pont.

Discerning an alien planet’s color is a difficult and time-consuming process, and it is only at present possible for a handful of exoplanets. To determine HD 189733b’s color, scientists had to isolate the planet's light from the starlight, using Hubble's Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph to look at how light reflected from the planet before, during, and after it passed behind its host star in orbit.

When the planet slunk behind the star, the light reflected from the planet was blocked and the amount of light observed from the entire sun-planet system dropped. But the drop in light was not uniform across the color spectrum – it was the blue part of the spectrum that dropped, while all other colors remained constant, suggesting that the planet is blue.

The foreign planet’s deep blue color is similar to the hue of Earth when seen from space: Carl Sagan once called our planet the "pale blue dot” – from the perspective of Voyager 1, out past Neptune, all of Earth's infinite dramas and stories, all its people and borders, recede into blue spot no larger than a pinprick.

But the two planets have little else in common. HD 189733b, some 63 light years from Earth, is a gas giant more massive than any planet in our solar system. Since it is orbiting very close to its host star, its atmosphere is broiling hot, with temperatures over 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit. For good measure, the atmosphere also rains glass in sideways blowing, 4,350 mile-per-hour winds.

“We discovered a completely different type of atmosphere,” said Pont. “We have nothing like it in our solar system.”

That punishing climate makes the blue color surprising not just on a scientific level, but also on a visceral one.

"It's very counterintuitive that this planet should be blue-colored. Because it was the size of Jupiter and was so close to the sun, we would have thought it would have a brownish, red color," said Stephen Kane, an astrophysicist at the NASA Exoplanet Institute.

Kane, who was not affiliated with the study, noted that planets within our own system tend to follow a red-hot and blue-cold color scheme.

That expectation of heat and color correlation in planets comes from biases based on our own solar system, he said, noting that astronomy often confounds our assumptions, especially as it ventures further afield, where each newly studied planets seems more improbable, more outrageous, than the last.

Pont said that his team’s study of nine other exoplanets akin to HD 189733b in that they are huge and close to their respective suns – known as hot Jupiters – has likewise offered up counterintuitive results: Given those basic similarities, scientists had expected them to be similar in other aspects. They aren’t.

“We’d like to put all hot Jupiters into one box, but they are as diverse as the planets in our own solar system,” said Pont. “That’s at once exciting and very daunting.”

While much is still unknown about other solar systems – as well as about our own – recent research has offered an increasingly clearer picture of worlds some light years away from ours, moving beyond exoplanet detection to exoplanet categorization, as we learn more about the atmospheres of those ultra-foreign planets, said Pont. He added that finding the color of exoplanets is an important step in those categorization efforts, much as determining the color of our own solar system’s planets has helped us better understand conditions there.

Earlier this month, new research that factored in the influence of cloud cover on alien climate brought a boon to exoplanet categorization, extending the habitable zone around red dwarf stars to include double the number of planets there. That added some 60 billion habitable planets to the existing number of potentially life-supporting planets in the Milky Way.