Mars heist: Red Planet was robbed of most of its atmosphere billions of years ago

Two papers report that Mars’s atmosphere was lost in cataclysmic events some 4 billion years ago, leaving the planet with too thin an atmosphere to support life.

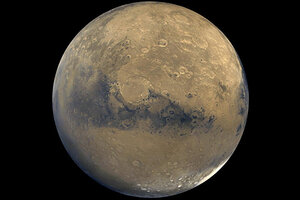

This photo released by NASA shows a view of Mars that was stitched together by images taken by NASA’s Viking Orbiter spacecraft. Two papers published in Science on Friday show that Mars lost much of the atmosphere that could have kept the planet warm and green about 4 billion years ago.

NASA/AP

Mars was robbed.

Two separate papers published in the journal Science provide evidence that Mars’s atmosphere was lost in cataclysmic events some 4 billion years ago, leaving the planet with too thin an atmosphere to support living organisms there. The findings, which show a shift in the proportions of heavy and light isotopes over time, join mounting evidence that the planet once had conditions conducive to life.

“Previous measurements had reported enrichment of heavier isotopes in [hydrogen], [carbon], and noble gases, and as an end result, models run backward in time indicated an atmosphere on Mars thicker than that of Earth’s,” says Christopher Webster, a scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the lead author of one of the studies. “Our Curiosity measurements are more accurate than previous measurements, so we can better tie our results to the time-scale provided by the meteorite record.”

Using data from Curiosity rover's SAM (Sample Analysis at Mars) instruments, scientists found that the heavy isotope carbon-13 is more prevalent in the current Martian atmosphere than it was in the past, relative to the lighter carbon-12, which has one fewer neutron. The same was true for the ratio of argon-36 to heavier isotope argon-38.

The change in proportions from the original material that formed Mars some 4.5 billion years ago indicates a violent and then gradual stripping of mass from the atmosphere’s top.

The loss of atmosphere likely began about 3 billion to 4 billion years ago, soon after Mars’s birth, said Dr. Webster. A huge impact from a Pluto-sized object, followed by smaller impacts, likely tore at the planet’s atmosphere, pocking the planet with the craters, including the Gale Crater in which Curiosity landed last summer.

Those impacts ruined the plant’s dipole magnetic field, which on our own planet diverts solar wind particles. Over the next few billion years, those particles careened into the atmosphere’s top, pulling more of that protective cover apart, he said.

Scheduled to launch in November, the Mars orbiting MAVEN probe is expected to fill in gaps in understanding of the current depletion of Mars's atmosphere, as those solar particles continue to thin its uppermost layer.

The new publications corroborate mounting evidence that life could have been possible on the Red Planet – but that about 3 billion to 4 billion years ago, the planet changed, becoming an inhospitable place.

“It is a good bet that the thicker atmosphere could have kept parts of the planet warm enough for microbial life to survive for a while,” said Paul Mahaffy of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, and the lead author on the other Science paper.

In March, NASA scientists reported that the first rock that Curiosity drilled into proffered critical, life-supporting elements, including hydrogen, oxygen, and carbon. It also contained clays, which form in water.

Then, this week, scientists at Caltech provided evidence of a delta into which an enormous Mars ocean might have once sloshed. Scientists there proposed that the ocean could have spanned about a third of the planet, feeding rivers and streams that girdled the foreign world.

But those findings are about Mars in the past tense: Curiosity, which has been on Mars for about a year and traveled more than a kilometer, has found no evidence of liquid water on the modern planet.

And NASA scientists report in these most recent papers that the methane levels on Mars are significantly lower than previously thought. In 2009, Earth-based measurements of the Martian atmosphere had found high quantities of methane gas there. Since most methane gas on Earth is produced by living organisms, and since the compound dissipates in just a few hundred years, its presence suggested that something was recently alive – or was still alive – and pumping gas on Mars.

Now, measurements taken from Mars’s surface show very little methane gas there – less than about 2 parts per billion. Lively Earth has about 1,800 parts per billion.

“The lack of methane in the atmosphere at the very trace levels that SAM can measure is surprising in light of previously published work,” said Dr. Mahaffy, noting that his team plans to continue searching the planet for the gas, in light of the data six years ago.

While scientists believe that the Red Planet could have once been warm and wet, it is still an open debate if life could have developed there before the atmosphere was tugged away, leaving the planet cold and dry.

“A big question that still needs an answer is how long the surface of the planet might have stayed warm and was this long enough for robust microbial life to develop and thrive,” said Mahaffy. “These are big questions that may take several missions and possibly returned samples or even future explorers on the surface to answer.”