Glowing robots: New skin lights up when touched

Scientists have created an interface much like a smartphone touchscreen, but pliable.

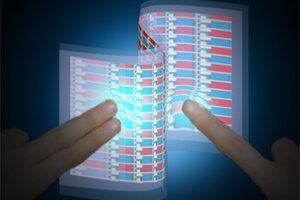

In this artistic illustration of an interactive e-skin device, the intensity of the emitted light corresponds to how hard the surface is pressed.

Ali Javey and Chuan Wang

Touch a future robot, and it might glow.

Researchers at the University of California at Berkeley have developed the first user-interactive sensor network on flexible plastic. That differs from the touchscreens on smartphones in that this material is thin and pliant, able to be wrapped around and adhered to a variety of objects.

And the material also differs from skin in that it, well, lights up. The so-called electronic skin, or e-skin, responds to touch with light: more intense pressure yields brighter light.

“We have made the "skin" interactive,” said Ali Javey, associate professor of electrical engineering and computer sciences at UC Berkeley and the leader of the research team on the e-skin project. “Where the surface is touched, it lights up with the brightness quantifying the magnitude of pressure.”

To make the e-skin, described in Nature Materials, engineers first hardened a thin layer of polymer on top of a slice of silicon, a semiconductor material. Once the polymer had toughened, the engineers ran it through with the same materials used in current touchscreens – organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDS), pressure sensors, and transistors. They then peeled the wired-up plastic from the silicon base. That left a plastic film thinner than a standard sheet of paper and embedded with a sensor network.

The project, which receives funding from Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), joins surging investment in developing robotic skin, keeping pace with mounting developments in robotics that have given those metal robots ever more useful, albeit skinless, hands and feet.

Most robotic skin projects have been modeled on human skin. Our sense of touch is received from our somatosensory system, wherein four different kinds of receptors in our skin feed information to our neurons and then to the brain. And so robotic skin would consist of sensors that communicate to the robot how much force to use in handling various objects.

It’s a simple request of a robot – don’t manhandle innocent things – but how to get a robot to feel its way through the world, as opposed to just seeing its way, has been a complicated, vexing problem in robotics.

In 2010, Javey and colleagues debuted pressure sensitive electronic material made of nanowires that could clothe a robots hands – the basis for his new, interactive material. In April, Georgia Tech released a robotic skin covered in thousands of nanowire transistors that respond to pressure, and the next month, ROBOSKIN, an EU-funded collaborative project between European researchers, debuted the prototypes for electronic sensors that could be applied to various robot’s touch points.

Those projects have mainly focused on bringing humans into safe contact with robots, but other researchers have veered toward developing the “super skin” that robots would need to roar into disaster zones. In 2011, Stanford researcher Zhenan Bao and colleagues prototyped a skin-like material that can detect not only extremely light pressure but also various chemicals. Her lab has also described a pressure-sensitive, electronic material – a nickel and polymer blend – that can self-heal, replicating human skin’s ability to do so.

Javey says that the new e-skin could have applications in addition to robotics. With some imagination, the pliable skin could be applied all over our world to make a huge variety of surfaces interactive, responsive to just a soft tap of the hand.

“Our vision for e-skin is beyond just robotic or prosthetic applications,” said Javey. “We are developing a new human-machine interfacing concept that consists of large-area sensor networks on thin flexible substrate that can be laminated on walls, tables, and all around us.”

Researchers at the lab are now hoping to develop an e-skin that can respond to light and heat, broadening the possible applications of the interactive interface.