Sun's magnetic reversal means big changes for the solar system

Scientists say that the sun will undergo a magnetic flip in the coming months, an event that happens just once every 11 years and the effects of which will be registered throughout the solar system.

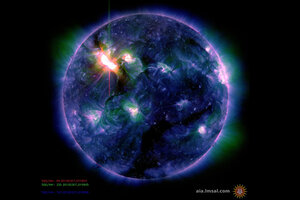

The sun, pictured as it erupts in 2012 with a major solar flare, is expected to reverse its poles in just a few months.

NASA/SD0/AIA/Reuters

Once every 11 years, something unusual happens on the sun: The sun’s polar magnetic field weakens, bottoming out at nothing. When the magnetic field appears again, it will be reversed. The sun’s north pole will go from negative to positive, and the south pole will switch from positive to negative.

Data from observatories supported by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration indicate that the next flip will happen in just three to four months – the north pole has already jumped the gun and reversed, and scientists are now just waiting for the south pole to catch up. The completed flip will herald changes throughout the entire solar system, according to a NASA video.

The sun’s magnetic influence extends some 8 billion miles through a region called the heliosphere. That region ends at the heliopause, the outermost boundary of our solar system that abuts interstellar space. So, when the sun’s polarity flips, the entire solar system will feel the effects of the change.

During the flip, what is known as the sun’s sheet – a massive surface some 10,000 km thick and billions of miles wide extending outward from the sun's equator – will become wavy. That wavy sheet will create cosmic “stormy weather” throughout the solar system. At the same time, it will also better deflect the cosmic rays spewed from distant supernovae than does a smooth sheet, protecting shuttles and astronauts from the particles.

The sun's magnetic field flips at the peak of each solar cycle, each of which are about 11 years long. This coming reversal will mark the midpoint of Solar Cycle 24, a solar maximum.

Solar maximums and minimums provide important data to scientists looking to create a better portrait of the still mysterious outer bounds of the solar system: Each change in the sun’s cycle provides an opportunity to assess how the sun’s particles from a minimum or a maximum behave in the altered solar system, and then extrapolate what the solar system’s outer boundaries looks like.

Last month, IBEX, NASA’s Interstellar Boundary Explorer in orbit around Earth, used data recorded from the sun’s particles spewed off during its solar minimum to prove that the solar system has a tail. At the time, scientists said that they were still awaiting data from particles released from the sun during its solar maximum, since those particles had not yet had enough time to ricochet toward the heliopause and then rebound back to IBEX.

Scientists have been monitoring the sun’s polarity since 1976, and have recorded three flips, with the fourth due this fall.