Moon-bound LADEE craft to fulfill NASA goal: communicate with lasers

The spacecraft LADEE, launching Friday night, aims to study the moon's atmosphere and dust. But it's also set to test laser communications that NASA hopes to use with future explorer craft.

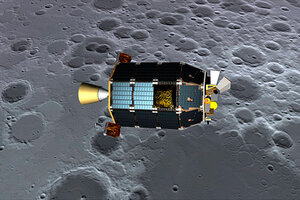

In this artist's illustration, NASA's Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer (LADEE) spacecraft orbits near the surface of the moon. The LADEE spacecraft is scheduled to be launched at 11:27 p.m. EDT on Friday.

Dana Berry/NASA Ames/Handout via Reuters

NASA is getting set to return to the moon with the launch Friday night of LADEE, an 844-pound spacecraft designed to analyze the composition of the lunar atmosphere and solve long-standing mysteries surrounding lunar dust.

In addition to its packed science agenda, however, the craft also is finally fulfilling a goal the space agency has had for more than a decade: to use lasers to communicate between Earth and spacecraft exploring the solar system.

The technology already has been tested with spacecraft in Earth orbit as a means of communicating between the spacecraft and the ground or between spacecraft, notes Donald Boroson, who leads the optical communications technology group at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Lincoln Laboratory in Lexington, Mass.

The lab designed and built the laser-based system as well as the main ground terminal for the demonstration project.

The approach has several benefits over the radio-based communications technologies NASA uses today, specialists say. Laser systems are smaller, require less power, and most important, they can send and receive far more information each second than comparable radio systems.

All of the operational communications between the spacecraft and the ground will use standard radio-based technology, passing information at up to 50,000 bits per second. These days, an inexpensive home wifi system can handle at least 150 million bits a second. The laser demonstration system on LADEE will beam more than four times that amount of information back to Earth each second.

If successful, the demonstration will set a distance record for laser communications, in addition to being the first system of its kind that NASA has flown or that has ever been used in the vicinity the moon.

Even before engineers put the system through its paces, however, NASA is eyeing the technology for upcoming missions, John Grunsfeld, who heads NASA's Science Mission Directorate, noted at a recent prelaunch briefing.

"It could be as soon as out Mars 2020 mission," he says, referring to the agency's next rover mission to the red planet.

"There's no question that as we send humans further and further out into the solar system, certainly to Mars, if we want to have a high-def, 3-D video, we're going to have to have laser coms sending that information back," he added.

Ironically, Mars was to be the technology's first deep space test, explains Dr. Boroson. NASA planned to launch a mission in 2009 dubbed the Mars Telecom Orbiter, which would have carried a laser-demonstration package. But the mission was canceled in 2005, a casualty of tight budgets and the high priority given to the final Hubble Space Telescope repair mission and other missions operating at the time.

Aboard LADEE, short for Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer, a laser whose power is less than about half a watt will be beamed to Earth via a 4-inch diameter telescope, hoping to catch the eye of three ground stations in Wrightwood, Calif.; near Las Cruces, New Mexico; and on the island of Tenerife in the Canary Islands.

The New Mexico station is the primary receiving site, with the others ready to step in if clouds obscure the site.

Establishing a solid link between the spacecraft and the ground station can be a challenge , Boroson says. The solution, he continues, was to equip the laser system on the spacecraft with a sensor that can detect a signal from within a patch of of the planet the size of New Mexico all at once.

Since pointing from the ground is somewhat more accurate than pointing a laser from the spacecraft, the ground station will initiate the communication process. Once the sensor picks up the laser light from the ground station it can center its own laser, which spreads from 4 inches at the spacecraft to nearly 4 miles wide on Earth’s surface, on the source.

LADEE is only a 100-day mission. After the laser demonstration with LADEE runs its course, NASA plans to test a similar system over several years between Earth and a commercial satellite in geosynchronous orbit, noted Don Cornwell, mission manager for the demonstration, during the preflight briefing.

"We hope that successfully demonstrating this over and over again...under all the conditions you can see in the atmosphere, day and night, will build the confidence for future NASA missions to use this technology for their communications system," he said.

The $280-million LADEE mission is scheduled to launch at 11:27 p.m. Eastern Daylight Time from NASA's Wallops Flight Facility on Virginia's Wallops Island – the first deep-space mission to use the facility since it was built in 1945.