More than 200,000 people apply for a one-way trip to Mars

Mars One, the foundation planning to put a human settlement on Mars in 2023, has received some 202,586 applications from pioneer hopefuls eager to live out the rest of their lives on the Red Planet.

Mars One has received some 202,586 applications from prospective astronauts hoping to colonize the Red Planet, yet untouched by humans.

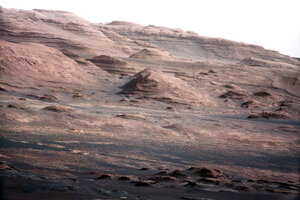

NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS/AP

One year ago, Mars One announced big plans for the Red Planet: a human settlement. The colonizing mission, planned for 2023, would be stylized like a reality TV show, but with the added drama that its participants, the would-be first humans to set foot on another planet, will never get to go home.

Despite that caveat, the foundation announced on Monday that it has received some 202,586 applications from hopefuls eager to live out the rest of their lives on another world – or, to be, exact, within 200 square meters of combined interior space and on a swath of the barren planet accessible only when clad in a protective suit.

“Its kind of a no-brainer to me, though I know that a lot of people don’t feel that way,” says Matt Ambler, a recent Yale graduate and an IT consultant in Washington DC who applied to be among the settlers.

“This is going to be a pretty important thing to do with my life,” he says. “Talk about leaving your mark on humanity.”

Mars One reported that the applicants came from 140 countries, with about a quarter coming from the United States, 10 percent from India, and 6 percent from China. Brazil, Great Britain, Canada, Russia, and Mexico, each put up about 4 percent of the applicants. All of the countries named in the applicant pool place above 100 in the UN’s Human Development Index Ranking for 2012, with the exception of China (101) and India (136), and presumably offer a higher quality of life than can Mars.

The foundation says it will select around six teams of four individuals in 2015. Those teams will spend seven years in training, and the first team will leave for the Red Planet in 2022, arriving the following year. After that, teams will arrive on Mars every two years, and the application portal will reopen to “replenish the training pool," according to Mars One's website.

The mission, which will be outfitted with technology purchased from private developers, to expected to cost about $6 billion, a point that the foundation has called its “biggest problem.”

So where will that money come from? Viewers like you.

The fictional Hunger Games, imagined in the 2008 book, fed on a population’s interest in watching people grapple with a 1-in-26 chance of being reunited with their families; Mars One expects that its pockets will brim with the investments of people eager to watch people with essentially zero odds of going home.

“People are interested in a manned mission to Mars; Mars One uses this interest to finance the mission,” according to the foundation's website, which cites revenue from Olympics broadcasts as evidence of what viewership can bring.

That means that, after Mars One removes the “unsuitable” applicants – applicants must meet certain physical requirements, including perfect vision and a height between 5’2” and 6’3” – viewers will have a say in who gets ferried to Mars, never to come home again, the group says.

Already, applicants who eschewed anonymity have posted videos on the foundation’s websites describing why the public should choose them to colonize Mars.

“You have to appeal to the public to go,” says Jessica Eicher, a senior at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Ms. Eicher's fiancé, David Barbeau, is also an applicant, and the couple expresses plans to become the extraterrestrial equivalent of Adam and Eve.

“Our shared dream is to have a family on Mars with the combined support of the entire human race,” writes Mr. Barbeau, a firefighter in Anchorage, Alaska, in his Mars One application profile. “After all, it takes an entire earth to raise an off world colony.”

At the moment, Mars One says on its website that it will “strongly advise the settlement habitants not to attempt to have children,” given the unknown effects of reduced gravity on conception and fetus development.

“We just feel like people would like us,” Eicher tells the Monitor. “Everyone can relate to a family.”

John Traphagan, a religion professor at the University of Texas at Austin and an advisor to Mars One, says that Mars One is above all looking for tolerant individuals who will cope well with the close quarters.

“The capacity to work well with others is exceedingly important,” he says, noting that in addition to screening for good-natured applicants, Mars One also plans to develop training schemes to prepare the would-be colonizers for the extreme isolation.

Still, all that might not be enough to ward against the possible physiological trauma of the Mars expedition, says Dr. Traphagan.

When Mars One launched in May 2012, the brainchild of Dutch scientist and entrepreneur Bas Lansdorp, the blowback was immediate. Besides physical safety concerns, like the effects of radiation on the new astronauts, there were social and psychological worries: Will the group be able to emotionally withstand seven months in a cramped and noisy spaceship, where the only available food is tasteless and freeze-dried and where a shower is just not possible?

Will those astronauts be prepared to cope with living out the rest of their lives with no expectation of seeing their friends and family ever again, or without hope of again experiencing the basic comforts – or even just the lapping waters and warbling birds – of their home planet? Will living what Traphagan calls “restricted lives” with no prospect for travel away from the base, nor anything new to see or plan or hope for, drive the perpetual astronauts mad?

And will these recruits be prepared to live until the end with just each other, or will this be a parable of how, as Jean Paul Sartre put it, “hell is other people”?

“We don’t know," says Traphagan. "Humans really don’t have much experience off our planet. We really don’t know what we’re getting into.”

To date, there have been a few studies on long-term isolation, in which participants have been quartered up and monitored for the sociological and psychological effects of such extreme togetherness. But Traphagan notes that participants in those studies benefit from a known release date.

“You know that the year is going to end,” says Traphagan “But on Mars, it doesn’t end. There’s no way to simulate going somewhere and never returning.”

Mr. Ambler, among those who have posted a video to Mars One, says that he is not afraid of the one-way-ticket aspect to the mission.

“That’s the whole point of a colony,” he says, citing the early American settlers. “You go there and you live there.”

Of course, what happened to the England's first attempt at a settlement in the New World, the 1587 Roanoke Colony, remains a mystery, and Mr. Ambler acknowledges that.

“I’m really not afraid of this," he says. "You can’t make an omelet without breaking a few eggs.”