Tilted planetary system throws planet-formation theories for a loop

Scientists have identified a system of exoplanets that are arranged at a tilt to their home star in a find that upends planet formation theories.

The Kepler-56 planetary system features two inner planets orbiting at a severe tilt to their host star -- even though there's no "hot Jupiter" in the system.

Daniel Huber/NASA/Ames Research Center

Scientists have found a multi-planet system in which the planets are arranged at a tilt to their home star. The finding, based on Kepler telescope data, offers an unusual level of precise detail about a system of worlds thousands of light years afield from our own, while also highlighting just how much is still unknown about how planetary systems form.

“As we discover more planetary systems, we're learning about the variety of 'architectures' that they display,” says Steven Kawaler, the leader of the Kepler Asteroseismic Investigation and an author on the paper, published in the journal Science.

“Every system has a different story to tell,” he said.

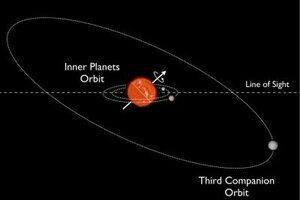

The new system is orbiting Kepler-56, a red giant that is four times the mass of the sun and some 3,000 light years afield from Earth. Two of the star’s planets are in close orbit around it. Another, larger object is orbiting the star farther out – that object could be a planet, too, but scientists aren’t yet sure.

The Kepler-56 system, one of hundreds so far discovered in our galaxy, is normal so far as exoplanet systems go – which is to say that it is “normal” in that, like most of these systems, it is unfolding to look little like what it had been expected it to look like and to upend what we thought we knew about the universe.

In this system, the perplexing detail that has thrown astronomers for a loop is its off-kilter arrangement: the star’s equatorial plane is at a 45-degree tilt to the three objects’ orbits. Though tilted orbits have been found before, they have appeared just in single planet systems where a hot Jupiter – an enormous planet similar in size to our Jupiter but orbiting near to its star and piping hot – was the lone companion to a star. Based on prevailing evidence, scientists had though that this tilt-a-whirl architecture must be unique to systems with a “hot Jupiter.”

And that had made sense, since, unless a traumatic event pulls things out of whack, planets tend to develop in neat alignment with their star, forming out of the thin disk of dust and gas swirling around the central star. In our own solar system, the eight planets all orbit the sun at no more than about a seven-degree tilt from the plane of the sun’s equator.

Put a hot Jupiter into that system, though, and everything rearranges. That’s because the formation of a hot Jupiter is believed to be a traumatic event in itself. It’s not possible to make a Brobdignagian planet close to a host star, since sufficient cold is required for enough ice and gas to fuse together to build an enormous planet. So, much as our Jupiter formed, hot Jupiters must begin in space’s cold, dark reaches, far out from a star’s warmth.

But, unlike our Jupiter, these grown-big planets end up in orbit near to their star, after gravitational interactions with nearby objects push them inward. There, the giant planet will become a “hot” Jupiter in the sizzling glow of its star. It will also, in all likelihood, have an unusual alignment.

“This process is like a complicated 3-D billiard shot, often resulting in an orbit well out of the original plane of formation of the planet,” says Dr. Kawaler.

It now appears, though, that tilted planetary orbits are possible in systems that don't have a hot Jupiter. That’s a find that could revise the basics of planet formation theory, suggesting that it’s possible that other, intervening forces must be accounted for in how systems develop. In this case, the researchers propose that the gravitational force of the third outer object is responsible for the tilt, pulling the two inner planets in line with its own tilt. Just what that object is, though, is still under investigation, the team reported.

“The final configuration of a planetary system tells the story of the formation process,” says Kawaler.

“If all systems form through a quiet accretion process, then all systems should have planar orbits around their host stars,” he said. “Systems with tilted orbits – and the degree to which such systems are rare or common – tell us that the planet formation process itself is highly variable.”

The Kepler telescope’s hunt for exoplanets has been hobbled since one of its reaction wheels was declared un-repairable this summer. But astronomers still have heaps of data from the telescope’s four-year-long gaze at the solar systems beyond our own. On Wednesday, NASA added eight new exoplanets to its catalogue of far-flung worlds, four of them dug out of Kepler data.

To date, Kepler has helped astronomers find some 3,589 confirmed exoplanets and exoplanet candidates. As of this week, NASA has confirmed the existence of 919 exoplanets.