Where were you when the Challenger exploded? Why your memory might be wrong.

Studies of so-called flashbulb memories, created during moments of emotional arousal, show that our recollections, vivid as they may be, are not necessarily reliable.

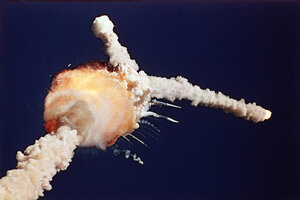

The space shuttle Challenger explodes shortly after lifting off from the Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Fla., on Jan. 28, 1986.

Bruce Weaver/AP/File

Do you remember when you first learned of the space shuttle Challenger's fatal mid-air disintegration on Jan. 28, 1986? It was a Tuesday morning in the US, and groups of schoolchildren were gathered around television sets to watch the orbiter lift off from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida. A charismatic high school teacher who was on board to teach science lessons from space, had drawn extra excitement to the Challenger's tenth mission.

But 73 seconds after the fiery liftoff, a seal failed, the vessel broke into a confusing tangle of smoke plumes, and something strangely permanent seemed to etch itself into minds worldwide.

Why do so many people seem to remember not only that heart-sinking footage, but the details of where they heard about it, who first told them, and how they described it?

The assassination of John F. Kennedy 23 years earlier, and the attacks on the World Trade Center 15 years later, left similarly widespread marks. All three events have prompted swells of scientific interest in the phenomenon known as "flashbulb memories" (FBMs). Why are they so vivid?

Cognitive neuroscientists are interested in FBMs because they seem to show how emotion – and especially stress – can influence memory.

Stress has been found to sharpen memory functions in both rodents and humans, and intense, negative shocks seem to leave behind vivid, detailed recollections. But an emerging body of evidence suggests that highly emotional memories do not tend to be particularly accurate.

"When I first heard about the explosion I was sitting in my freshman dorm room with my roommate and we were watching TV," wrote an Emory University student who participated in a memory study a year and a half after the Challenger disaster. "It came on as a news flash and we were both totally shocked."

But that same student had given a surprisingly different answer, just 24 hours after the tragedy. "I was in my religion class and some people walked in and started talking about [it]," she wrote. "I didn't know any details except that it had exploded and the schoolteacher's students had all been watching which I thought was so sad."

The researchers who had hustled to gather these reports found that by 1988 and 1989, not one of their 44 subjects remembered the Challenger's explosion the same way they had in its immediate aftermath.

A similar study conducted after the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center, found that 42 percent of the inconsistencies that arose were for basic details like the time, place, and participants' activities when they first heard the news. And yet the subjects' recollections, erroneous as they may have been, also remained extremely coherent and vivid.

Those scientists concluded that FBMs don't create particularly accurate memories, but they do create a strong conviction that the memories are accurate.

Some have theorized that this disconnect can be understood in light of the Yerkes-Dodson Law, which describes a bell-shaped relationship between arousal and performance: when a mind or body is aroused, it performs better, but only up to a point. When we get too excited, performance decreases.

Why would this be?

Earlier this month, University of Western Ontario researcher Michael Salma speculated that it might have conferred an advantage, "as fight-or-flight responses to a threat (for example, a predator)… necessitated that resources be spent attending to threats, rather than encoding peripheral details."

The news that intense shocks can create simultaneously vivid and inaccurate memories may carry legal implications, suggests Mr. Salma.

"Unwarranted confidence in memory recall has concerning implications in eyewitness testimony, where confident witnesses could mean the difference between a sentence and an acquittal."