Artificial muscles from fishing line? New possibilities.

New technologies emerge as researchers find ways to produce artificial muscles from polymers. From artificial limbs to robots to temperature-controlled clothing, the range of possible uses is vast.

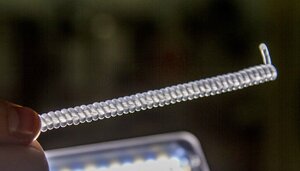

Researchers at the University of Texas at Dallas have created artificial muscles by twisting and coiling ordinary fishing line. High-strength polymer fibers can be transformed into efficient artificial muscles, according to a research article published Friday in Science magazine.

University of Texas at Dallas/REUTERS

From humble parts – No. 6 fishing line or nylon thread – researchers have produced artificial muscles that can lift 100 times the weight that a comparable human muscle can lift, and they've made them from a process as simple as twisting a toy airplane's rubber band.

The too-good-to-be-true simplicity of the components and the apparent ease of designing and making the muscles could speed the evolution of a range of technologies – from wearable exoskeletons for the military and artificial limbs for amputees to robots to clothing whose weave adjusts to changing temperatures and window shutters that open and close as temperatures change.

"The application opportunities for these polymer muscles are vast," said Ray Baughman, a materials scientist at the University of Texas at Dallas who guided the research, in a prepared statement.

The quest to make artificial muscles, which also can be used as motors, has been under way for years. But the components – bundles of carbon nanotubes or metals with "memory" that return to their original shape when heated, for instance – have been exotic, expensive, and in some cases hard to control.

By contrast, making artificial muscles this new way requires nothing more complicated than a quick search of a tackle box and sewing kit. The team's goal was to see if it could devise faux muscles that equal or beat the capabilities of human muscles from materials available for about $2 a pound. Wire made from memory metals carries a price tag of $273 a pound.

The artificial muscles get their energy from heat, which can come from light, electricity running through thin wires or metal strands built into thread, chemical reactions, or even the surrounding environment, the researchers say.

As for the movements the muscles perform, it's all in the twists and temperatures.

The thread and fishing line consist of long, chainlike molecules known as polymers. By twisting a length of either type of line, the researchers produced a muscle that spun a rotor at up to 10,000 revolutions a minute. When heated, it spins in one direction, then reverses direction when cooled, Dr. Baughman says in an interview.

When the researchers gave the thread or fishing line additional twists, the lines formed long tight coils, much like an overly twisted rubber band in a model plane. The resulting artificial muscle would grow shorter when heated and longer when it cooled.

If the tightly coiled fishing line or thread was wrapped around another form, such as a glass rod, the team found that it could reverse the action the temperature changes imposed, depending on the direction of the windings.

The artificial muscles contracted by about half their original length, compared with 20 percent for human muscles. And the artificial muscles could be cycled through expansion and contraction millions of times.

In another experiment, the team gathered four lengths of fishing line into a bundle about 10 times the diameter of a human hair. When they twisted the bundle into tight coils, the artificial muscle was able to lift 16 pounds. The researchers estimated that muscle formed from a bundle of 100 strands of fishing line, tightly coiled, would be able to lift 1,600 pounds.

"We were very surprised that this really works," Baughman says.

What he found truly stunning, he says, was the amount of power these muscles can generate for their weight – more power per unit of weight than an internal combustion engine.

"That just knocked my socks off," he says.

The project, described in Friday's issue of the journal Science, involved researchers from six countries. Baughman and colleagues, including the paper's lead author, Carter Haines, also at the University of Texas at Dallas, focus on these artificial muscles for use in mechanical devices. But some researchers suggest that the work may hold clues for finding materials to use to repair damaged human muscles.

"I think this is neat," says Thomas Webster, who heads the chemical engineering department at Northeastern University in Boston and focuses his research on using human-engineered materials as replacements for human tissue.

He cautions that to call the devices Baughman and colleagues produced "muscles" could mislead some people into thinking that a new tool for restoring damaged human muscles is at hand, which is not the case.

Still, the results are valuable to his own work, he adds. The twisting mechanism that Baughman, Mr. Haines, and colleagues uncovered resembles the action of biological muscle fibers, which have coiled structures that twist as muscles stretch and contract.

A lot of the materials that researchers are exploring as stand-ins for muscles don't bend or twist in the same way the fishing line and nylon thread do, he says.